Empathy Test

by Nicolas Rapold

The Assassination of Richard Nixon

Dir. Niels Mueller, U.S., ThinkFilm

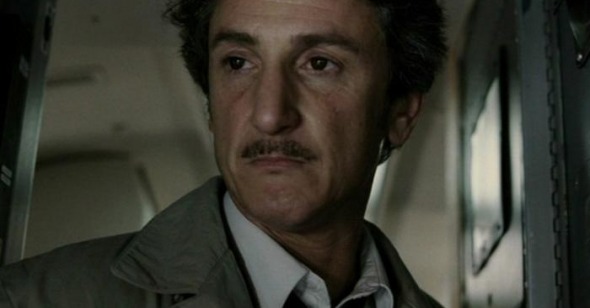

The Assassination of Richard Nixon relates the tale of historical footnote Sam Byck, who planned to kill the huckster-in-chief by hijacking a plane and flying it into the White House. In the context of a jingoistic or indifferent media, putting “assassination” in a title is transparent titillation, the promise of a Falling Down for liberals with the frisson of sedition. But the mechanical screenplay by first-time director Niels Mueller and Kevin Kennedy (Tadpole) destroys both suspense and sympathy, and distancing techniques in camerawork and narrative hobble another “soul-baring” performance by Sean Penn. Ultimately, the film's literalist mission expresses a revealing political nostalgia far more interesting than any buzz-ridden grab at relevance.

The history of assassination is shot through with an anxiety (or psychosis) of influence-both onscreen and off. The six-degrees genealogy of deadly one-hit wonders is worth reviewing: Assassination's subject, Sam Byck, tried to kill Nixon; two years earlier, Nixon's segregationist counterpart George Wallace was shot by Arthur Bremer; Bremer's diaries yielded Paul Schrader material for Travis Bickle; and Bickle inspired John Hinckley to shoot Reagan for Jodie Foster. It sure is a small world!

Real-world psychotics aside, a portrait of a lonely killer like Byck (“Bicke” in the film) inevitably contends with the seductive text of Taxi Driver. The films are too different for a fair comparison, but Assassination does invite scrutiny through common technique (voice-over narration from the subject's writings) and scattered references (Bicke watches Nixon ballroom-dancing on TV, like Bickle staring at “American Bandstand”; he also rehearses dialogue for a confrontation). Taxi Driver's muscular process of identification is notoriously problematic (I like Jonathan Rosenbaum's take), but Assassination runs far into the other direction: the key divergent decision is to replace the complex charisma Taxi Driver constructs for Travis with a distancing that allows only pity, and ultimately not even that.

Penn's Bicke is the picture of a sad sack, who, before the film even begins, has already experienced failures both personal (separation from wife, who, worse, is Naomi Watts) and professional (quit job at brother's store). The job loss is revealed as a casualty of Bicke's refusal to push the hard sell, part of a greater idealism about the compromises of dignity and ethics that the all-American pursuit of money fosters. But although Bicke is repeatedly shown explaining his reservations about business tactics, the reasons for the marital separation are never spelled out-a telling and cruel omission that leaves the viewer to judge Bicke from the variety of unflattering moments prior to his total deterioration. The bulk of screen time consists of this sad litany: Bicke's humiliation in a new job at the hands of a Dale Carnegie-abiding boss (an all-American character played well, in a meta-humiliation, by Australian Jack Thompson); futile visits with his estranged but patient wife at home and at work; and foregone attempts at securing a bank loan for a ridiculous business venture (a tire-store-on-wheels).

Mueller frames many scenes, especially as Bicke awaits the loan decision, with what might be called “pity shots”: the camera hovers on Penn in an empty room from a middle distance, sometimes peering around the edge of a doorway, like an uncomprehending and frightened child that discovers a parent crying. Mueller signals tension or instability in many scenes through the tic of constant slight frame adjustments, a hackneyed “documentary” nod to the story's factual basis. Less flashy scenes are dispatched to a safe psychological distance through an emphasis on ludicrous content: the bank visit, at which Bicke actually produces a crayon drawing of the “tiremobile”; or the fraternal call on a Black Panthers office, where Bicke proposes the name “Zebras” to express racial amity with downtrodden whites.

Yet it is the retrospective structure of the voice-over that clinches Bicke's character development as a foregone conclusion. Mueller opens the film and punctuates sequences with Bicke reading lines from letters sent just before the assassination attempt but after most of the film's events. One can imagine the counterpoint of future Bicke with present Bicke eliciting wonder at what he would become, but the overwrought, maddened sentiments instead highlight all the weirder details and moments that appear even early on (e.g., the tire bus, stalking his wife). To clinch things, the letters are addressed to Leonard Bernstein-a screaming marker of unbalance that extinguishes any suspense about the character's trajectory and further primes one's sensors for looniness.

Similarly, music cues (which Rosenbaum shows to be so crucial in buttressing Travis urban romanticism) undermine Bicke from the outset. A child's music-box jingle opens and closes the film and helps infantilize Bicke's idealistic refusals to compromise on the job (a rhetorical move reminiscent of Republican idiom). And, in an interesting instance of generic development, the repetitive Glassian motif that unwinds on the score evokes the borderline subjects of late Errol Morris, who, like Bicke, are forever explaining themselves (in portraits that, absent the controlling influence of a Robert McNamara, slide queasily between fascination and derision).

In the schematic narrative of Assassination, such tactics ensure that events never rise above exposition for a breakdown. The push and pull of the direction tends to strand Penn's later Hurlyburly-caliber apoplexy unfairly, though beautiful moments of quiet suffering survive, such as Bicke's lingering needful embrace with his friend's kid. But Mueller is too preoccupied with presenting a precise trajectory of a loser, and scenes with his so-called friend (played with a disquieting flatness by Don Cheadle) lack sympathy alarmingly early. (For a more graceful alternative, I kept fondly remembering Christopher Walken in Catch Me If You Can as the ineffectual father who sees success as a club that he could never quite crack.) Ultimately, Assassination refuses to allow even pity, taking the time to show Bicke, out of character even for being out of his mind, shooting his dog in the basement.

But there is something that Mueller and Kennedy's portrait resembles in its nervous distancing and slavishness to a flow chart of provocation/reaction. If Assassination fails as a moving psychological (or historical) study, it functions flawlessly as the age-old official profile of the lone assassin-the sort of dead-end pop-psychology that stymies further investigation (or dangerous sympathy) through a self-contained and self-consuming narrative. Who did it? This crazy guy. What happened? He lost his job and his wife. Why did he do it? He went crazy. The parade of oddball loners that strafed American leadership were likewise presented simply by government and media and were, to say the least, deeply unsatisfying, and the Byck of Assassination is little different.

Taxi Driver interprets its source materials in ways calculated for appeal (Bremer was no De Niro), but Mueller and Kennedy have made systematic choices, too, in portraying Byck not as unappealing but as inherently out of appeal's reach. And with this approach, the expositive profile replacing character study, they align themselves with a highly circumscribed, fundamentally institutional mode. In the real world, such a mode is a brute-force therapeutic approach that, in a crisis, seeks to minimize meaning, to halt an awful story-in short, to stop the bleeding. But you don't have to subscribe to a Parallax View of the era to desire simply a deeper, more satisfying understanding, paradoxes and all, and to resent the almost organismic tendency of institutions to resist analysis in maintaining continuity. For if the profile approach seems sensible for a nation in upheaval, it can make for cautious and mediocre cinema.

But it is the final shot that confirms Assassination as a nostalgia piece in more ways than one. After the climactic failed hijacking (portrayed in the haze of Bicke's by-then fugue state) and subsequent news coverage (and after Bicke actually says “They will never forget me”), there follows a coda, a brief shot in flashback. Bicke runs through his living room, playing with a toy airplane, and, running, turning, he flies the plane right into the camera-cue blackout. Amounting to the last gasp at the end of a horror film-the oblique it-could-happen-again! threat-hope attraction-repulsion-the shot returns the film definitively to the September 11th nexus of the plane-as-weapon, which was probably the chief reason, in the literalist Hollywood calculus of “true-story” appeal, for the film's existence. The tinkly children's music box of the film's opening reappears, but here, unwittingly or not, the evocation exceeds Bicke-as-idealist-manchild to include, with the plane's collision, the audience-infants in a new world order.

Yes, who knew, but those were the good old days, when assassins were old-fashioned whiners, losers who lost because they couldn't play the game. For the loner profile is no less than relief from the new unfathomable: Islamist fanatics, likewise idealists but of a higher calling, who could care less about any game outside of a religious absolutism twisted around the contours of political opportunism. Given the current impossibility of rendering geopolitical history—forget psychological profiles—without accusations of treason, it is small wonder that the filmmakers, as if sensing some ur-need, have produced the alternative to revenge dramas like Man on Fire: the oblivion of nostalgia, homegrown retro chaos safely beyond the horizon line of pop history.