The Home and the World

By Lawrence Garcia

NYFF:

The Last City

Dir. Heinz Emigholz, Germany, no distributor

The Lobby

Dir. Heinz Emigholz, Germany/Argentina, no distributor

R.W. Fassbinder once remarked that he sought to build a house with his films, but it is German director Heinz Emigholz who may ultimately come to realize this dream. Over the past quarter-century, he has emerged as Germany’s—if not contemporary cinema’s—premier chronicler of architecture, producing films variously corralled under the series titles “Photography and Beyond” and “Architecture as Autobiography.” These works impress not just for their range of subjects (architects such as Rudolph Schindler, Bruce Goff, Samuel Bickels, and Robert Maillart), but also for their stylistic consistency—they largely comprise a systematic progression of canted, almost Cubist compositions of various edifices, accompanied by each space’s ambient noise. Initially, these spatiotemporal explorations were born of mere practical necessity: unable to finance new narrative work in the nineties, Emigholz took a tentative turn into relatively cheap architecture documentaries, while also teaching at Berlin University of the Arts. But over the years, as this increasingly prolific career track gained momentum, the stylistic approach he developed and refined has come to be the cornerstone of his artistic legacy.

Emigholz’s two most recent features, The Last City and The Lobby, would be impossible to mistake for the work of any other filmmaker. But while they remain preoccupied with related questions of space, they are marked by a few salient differences from this earlier work. In contrast to the commentary-free and mostly unpeopled architecture films, both expand on the absorbingly talky Streetscapes [Dialogue] (2017), which emerged out of an intensive set of psychoanalyst sessions undertaken by Emigholz during a bout of deep depression. Thus elaborating on the director’s reintroduction of language and human presence in his cinema, The Last City unfolds as a set of disparate conversations, while The Lobby resembles something more like a theatrical monologue. In addition, the former marks the 72-year-old director’s return, after a fashion, to narrative filmmaking.

That last assessment is admittedly imprecise. For one thing, it suggests a more definite documentary/fiction divide in Emigholz’s work than is really possible to determine. For another, it fails to account for how unconventional his conceptions of narrative are to begin with. A bizarre mélange of Jarmanesque homoerotic tableaux, death-obsessed comedy, and scattered musings on art and architecture, his third feature The Holy Bunch (1991) assembles a posthumous portrait of a dead editor through five friends’ efforts to make sense of his notebooks. Similarly five-pronged in conception, though more straightforward in structure, The Last City progresses along a series of daisy-chained dialogues across five cities (Be’er Sheva, Athens, Berlin, Hong Kong, and São Paulo), impelled not so much by character or story as by conversational momentum. But even a list of the subjects discussed—weapons design, the generational divide, family, war guilt, and cosmology—can’t begin to convey the experience of actually watching this spry, sinuous, altogether surprising feature.

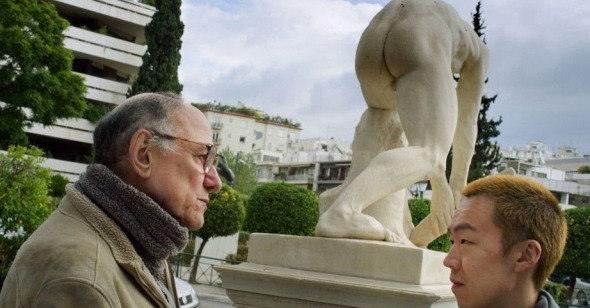

This frustration with human means of expression, though, is part and parcel of Emigholz’s purposes. “It was a straight lie when I told you that I had an image that could describe the state of my depression,” John Erdman tells Jonathan Perel in The Last City’s opening section, both actors seeming to reprise their respective artist/psychoanalyst roles from Streetscapes. We soon learn that Erdman is here playing an archaeologist, Perel a weapons designer, and their wide-ranging conversations mostly revolve around the latter’s work. But once the film relocates to Athens, leaving Perel behind to follow a gay artist (Erdman again) who encounters his younger self (Young Sun Han), it becomes clear that, even more than his stated litany of subjects, Emigholz is interested in the difficulty, if not the impossibility of fully conveying one’s private experience—even, or especially, through images. Hence, the necessity of being attentive to what we are able to see.

In a 2013 interview in German Film Quarterly, Emigholz stated his views on the matter clearly: “The very last thing I want to do is break open the world’s surfaces to discover some sort of secret code behind them... Instead, I am convinced that it is these very surfaces that should be speaking to us… The fact that a ‘reading’ of surfaces is practiced so little in our supposedly oh so visual culture is not restricted to the phenomenon of ‘art,’ of course.” One’s perception and “reading” of a surface are after all fundamentally phenomenological matters, so The Last City’s first two movements are maybe less about weapons design and age gaps than about professional biases and temporal perspectives. Likewise, the third, Berlin-set movement, which restages the cigarette-smoke kiss from Genet’s Un chant d’amour (1950) in a Catholic confessional, between a priest (Young) and his policeman brother (Laurean Wagner), seems less concerned with adjudicating certain taboos or family structures than with interrogating the conventions and assumptions that undergird them. If Emigholz’s polyphonic work might be said to have a single purpose, it is to help us see—or to get better at seeing—the order of things.

It is in this sense that the German director might be considered a provocateur. Filled with any number of shock tactics and instances of surprisingly bawdy humor (an illustrative joke: Erdman and Young quickly discarding the idea of fucking one’s younger/older self), The Last City continually trades on a pervasive, pointed sense of absurdity, underscoring our distorted perceptions of the world and its sundry surfaces. If Emigholz’s architecture films, with their extraordinary attentiveness to matters of space and dwelling, were meant to close the gap between ourselves and our surroundings, his visual and narrative syntax in The Last City purposefully attempts to widen it, opening the film up to breathless bursts of comedy. His steady editing patterns, which tend not to vary with the words being spoken, here only add another dimension to the actors’ delightful deadpan. In a similar way, the film’s visual gags only become more ridiculous as the subjects under discussion become more severe. In Hong Kong, scenes of a Chinese woman (Dorothy Ko) ordering a Japanese woman (Susanne Sachsse, definitely not Japanese) to commit seppuku as penance for her nation’s war crimes culminate with the neon sign of a sausage stall (“German–Japanese Guilt Wurst”) and some Sweeney Todd–like implications. Later, in a subterranean São Paulo safe house, a conversation on interplanetary life and cosmic coincidence is followed by that most banal of chance narrative occurrences—a car crash.

It is one measure of Emigholz’s achievement that The Last City cannot easily be slotted into any familiar cinematic template. But without negating the German director’s stated desire “to develop a new narrative,” it can be said that he shares something with Lars von Trier. One would be remiss to overstate the similarities, which are more a matter of sensibility and critical preference than aesthetic style—after all, whereas Emigholz channeled his deep depression into Streetscapes [Dialogue], von Trier directed his own into Antichrist (2009), Melancholia (2011), and Nymphomaniac (2013). Still, apart from sharing a taste for impish comedy, a fascination with taboos, and an instinct for provocation, both filmmakers in addition have a rare fondness for circumlocutory exchanges that operate either as philosophical dialogue or psychoanalytic session.

Or, in the case of The Lobby, as hectoring, logorrheic monologue—on the surface at least. Here, Erdman plays a character credited only as Old White Male—an arguably redundant designation—who goes on about everything from Hegel and “the unhappy consciousness” to the ills of consumerism to anecdotes about shitting bulldogs and women with extra-long fingernails. As in The Last City, Emigholz’s typically effortless découpage (again accomplished with regular co-editor, Till Beckmann) transports Erdman through a variety of lobbies of apartment high-rises and office buildings in and around Buenos Aires. Old White Male’s preferred topics range widely, though at bottom they all come back to death, which creates the impression that these nondescript spaces are something more like Sartrean waiting rooms. (For Erdman’s somewhat Bruno Ganz–like presence, one might recall the walk-in freezer near the end of von Trier’s The House That Jack Built.) And indeed it would be a kind of punishment to be locked for eternity with Old White Male—though he seems only too aware of this, periodically goading the viewer to leave by asking how many people have at that point walked out of the theater. He seems to resent that we even have the option of leaving.

On its own, The Lobby might play like little more than a diverting experiment, combining a confrontational monologue with the unemphatic cadences of Emigholz’s architectural films. But taken alongside The Last City, it more clearly expands on that film’s explorations of identity and perspective: as he belongs to that most privileged of demographics, Old White Male is the most provocative choice to deliver a didactic disquisition on death. To look at one work in the crosslight of another is, of course, a common procedure of auteurist advancement, but because of Emigholz’s prolificity and his tendency to reconfigure recurring elements of style, one might be less inclined to judge the limitations of any individual work too hastily. For in his oeuvre, it is entirely possible that a subsequent effort might throw this one into sharp relief. Upon its premiere in 2017, Streetscapes [Dialogue] was rightly greeted as a major achievement of an artist who hasn’t always gotten his due. In retrospect, it’s also clearer that the film was not a one-off aberration, but the beginning of a new phase of construction.

With The Last City, Emigholz has made a film nearly as accomplished as Streetscapes, and with The Lobby, something decidedly lesser. But if there’s any constant in Emigholz’s films, from his decades-long architecture work to his more recent not-quite-departures, it’s the awareness that such judgments are contingent—the house is, after all, not yet complete. The important thing is that we look and look again.