Bare Knuckleheads

by Justin Stewart

Fighting

Dir. Dito Montiel, U.S., Rogue Pictures

Fighting's chief auteur might be producer Kevin Misher, who also helped greenlight the first Fast and the Furious movie. Logically wanting to replicate that film's massive success outside of the franchise, he sought another illicit world of extreme hetero recreation. And as in the earlier film, he wanted race and ethnicity to not interfere with the characters' interactions, to show that "the thrill of the sport" trumped such pointless, dying concerns. That almost utopian aspect of both movies is appealing. Pretending such matters of identity don’t exist is a just a stubborn, cheeky way of repudiating racial conflict.

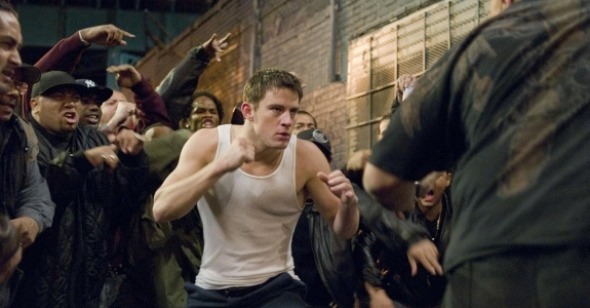

As per the title, the excuse for the movie this time is the illegal bareknuckle fighting scene in New York, in which Wall Street yupsters and various bored, rich shysters bet large stakes on brutal amateur bouts. The buff, blandsome Paul Walker character here is Shawn (Channing Tatum), raised in Alabama and relatively new to New York, where he's scraping by selling knockoff books (like Harry Potter and the Hippopotamus) off the street in midtown. A scam artist named Harvey (Terrence Howard) senses Shawn's cash potential when he sees him fight off some punks trying to filch his merchandise. It's unclear how Harvey could so accurately suss out his fighting ability from this ten-second scuffle, but he's soon Shawn's agent, earning him entrée into the lucrative underground. Thinking his fighter will have a special premium because he's a "white boy who went to college," Harvey is only laughed at.

Tatum, star of the Step Up movies who's playing Duke in the upcoming G.I. Joe picture, is not as good-looking or "intense" as Walker. He has the same numb but all-in-the-right-place features as Josh Hartnett, yet he never hints at a deeper intelligence. His Shawn, in short, is a dolt, a hunk failed by words who speaks in monosyllables and fists. When he makes it into the bed of a girl he likes, "this is nice" is the best he's able to mumble to her. The movie doesn't make apologies for Shawn's simplicity, though a backstory involving a tyrannical father/coach explains his pent-up rage.

Fighting's street philosophy instead comes mouthed by Howard, one of the most off-putting actors working today. In the song "Stereo," Pavement asked about Rush's high-pitched Geddy Lee, "I wonder if he speaks like an ordinary guy?" If you want to know why Howard uses the same spacey, babylike murmur in all his roles, the answer is probably that it's just how he speaks. If Fighting wasn't so trivial, you'd be upset that Howard's line deliveries—some of the strangest since Zooey Deschanel's in The Happening—keep taking you out of it. He cuts off letters of words at random, emphasizes the wrong ones, and generally speaks like he's from another planet. "He always calls me Haah-vee," he complains about Luis Guzman's Martinez. "Let's make sahm money," he says to Shawn. Harvey, whose pajama bottoms can be seen peeking out underneath his slacks, becomes wistful when quoting his dad ("He used to tell me that nothing good ever happens after 10 p.m.") and discussing his hometown ("I'm from a place with some culture: Chicago.") The character's a mentor in the mold of Ratso Rizzo and Paul Newman's Fast Eddie Felson in The Color of Money, given its own color by Howard's sad distractedness.

Fighting is structured around four major fights (rousing, blender-edited affairs that often spill out through walls). The plumber's putty in between consists of Shawn and Harvey's contentious but chummy relationship, Shawn's romance with Zulay (pronounced like July and played by Zulay Henao), and the guff about Shawn's southern past. The methodical plotting works, but assures no surprises. Fighting deserves some credit for the clichés it avoids—there's no girlfriend or parent futilely trying to urge Shawn "out of the game," and Harvey never double-crosses Shawn, which would normally seem inevitable.

Director Dito Montiel is a Queens native, and he's aggressive about selling this as a "New York movie," with emphasized borough-hopping and ceaseless helicopter skyline shots. But since the most important action happens indoors, all the overstressing of the location leaves you cold to the fact. Montiel's previous film was the autobiographical A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints, the story of the adult Dito's return to his violence-plagued Queens upbringing, which also featured Tatum as a fight-prone thug. Though miscast and flat, Saints is watchable thanks to the authentic feel for New York that Fighting oddly lacks. There is some city commentary shoehorned into the newer film, though. Listening to a woman shout about new buildings in midtown, Harvey tells her, "Don't worry. It's okay. Move on." Later, at a fight in the Bronx, he says, "Bet they won' complain abou' them putting up buildings here." The sentiment's not entirely clear here, but it's welcome to see Kevin Misher's nonracial cinematic bubble pierced by something like class conflict.