Unholy Redeemer

by Kristi Mitsuda

Julia

Dir. Erick Zonca, U.S./France, Magnolia

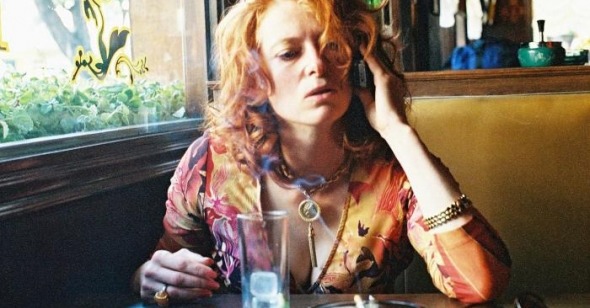

Julia is your typical tale of redemption, even as it thrashes against the sentimentality such a designation implies. As fearlessly played by Tilda Swinton—so often cast in roles for her androgynous appeal or otherworldly, reptilian bloodlessness, but here afforded leeway to get down and dirty—the titular protagonist is a full-blooded human yet completely unsympathetic at first. Self-destructive Julia sees herself as mere victim of a shitty world, refusing to take responsibility for her woes. Everything about the woman is abrasive, from her garish red hair and purple coat to her inebriated come-ons and morning-after put-offs. At the start of the film, you can’t imagine ever empathizing with this woman; it’s a credit to Swinton’s skills that you eventually warm up to her despite the script’s refusal to completely soften her up.

Opening his film on a not-unusual night out for the besequined and glitter-mascaraed lead, Erick Zonca (the French filmmaker responsible for the sublime The Dreamlife of Angels) renders in rambling fashion Julia’s alcoholic pattern: After partying and picking up a conquest, she literally awakens the next morning to the harsh, unflattering light of day, seemingly surprised to find herself in a stranger’s car. Arriving late to work only to be fired for her last-straw tardiness, Julia would seem to have hit rock bottom—but she’s far from it. Her downward journey doesn’t truly begin until she meets a young woman named Elena (Kate del Castillo) at an AA meeting, setting off a chain of events soon to result in a fucked-up kidnapping effort of near Fargo proportions, minus the leavening humor or efficiency of the Coen brothers.

At first, Elena’s twitchiness comes off as nervous and shy rather than symptomatic of a disturbed nature. Julia, smoking and hiding out by the snack table in order to avoid engaging other members of the support group—which she only attends at the behest of friend Mitch (Saul Rubinek) in exchange for a loan—makes no effort to disguise her annoyance at Elena’s solicitousness upon the realization that they’re neighbors. But Elena pays no heed, launching into her life story, the structuring absence of which is her eight-year-old son, Tom (Aidan Gould), who now lives with his paternal grandfather. One morning shortly thereafter Julia awakens on Elena’s couch after having passed out in the parking lot the night before, and the film switches gears as the woman rants about a plan to steal her son back, promising to pay Julia a large sum of money from apparently vast reserves hidden in Mexico if she helps.

Julia reconfigures the plan to kidnap the child herself in order to extort more money, and viewers can’t help but question who’s crazier—Julia for believing unhinged Elena, or Elena for enlisting the help of a drunk she barely knows in a criminal enterprise—a tension which captures the extent of each woman’s desperation. No surprise, the ransom gambit goes awry; Julia, ridiculous in a black mask, knee-high boots, and red leather jacket in the forested abduction spot, snatches Tom from his caretaker and leaves a bloody mess in her vodka-infused wake. Although apparently loosely inspired by John Cassavetes’s Gloria, the film evinces few similarities to that earlier film other than the basic set-up featuring a white woman going on the lam with a half-Mexican kid.

Somewhat embedded but unearthed here is a subtextual narrative involving U.S.-Mexico relations. Julia tells Tom of his heritage, extrapolating stories of his white father and Mexican mother from details Elena related to her (somehow, Swinton even manages to deliver the standard, saccharine line, “You look like her; you’ve got her eyes” with a level of flinty self-awareness attuned to the character); later, she and Tom inadvertently hide out in the California desert near an illegal border crossing, ultimately driving into Tijuana themselves. But, set at first in multiethnic Los Angeles, Julia squanders opportunities to present background cross-cultural noise; the city isn’t rendered in a particularly recognizable, relevant, or resonant way, and no thematic expansion occurs once the pair crosses the border, a disappointment given Zonca’s complex rendering of human interaction in Dreamlife. His direction, so assured in his debut, here seems impersonal, exacerbated by an unwieldy running time which leaves too much room for slack.

Although Julia’s initial behavior towards Tom—in which she waves a gun maniacally in his face and forces him to take sleeping pills—makes almost inconceivable the prospect of the relationship devolving into the cliched Stockholm-syndrome bond between captor and captive, the narrative slowly crawls there. Baby steps include Julia promising the boy not to tie him up anymore, sharing a Mexican meal together in a restaurant, and, finally, literal (and slightly discomfiting) cuddling. Right up until the end, though, Julia commits acts so dunderheaded and morally heinous that the redemptive conclusion smacks of an inauthenticity even Swinton can’t quite temper.