Toeing the Line

by Eric Hynes

Every Little Step

Dir. James D. Stern and Adam Del Deo, U.S., Sony Pictures Classics

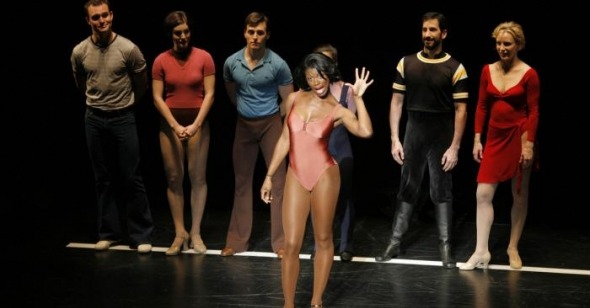

Part tribute to A Chorus Line creator Michael Bennett and part comparative chronicle of both the 1975 original and 2006 Broadway revival of his Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning musical, Every Little Step covers a lot of ground in 90 minutes. There’s plenty of memorable material, from Bennett’s reel-to-reel audio recordings that became the basis for the show’s celebrated monologues to candid footage on stage and off, archival and new. The film imbues it all with a respect for performance that reflects that of the play’s creator, documenting the revival’s rigorous casting process with affection and awe.

Although it makes for a pleasing package, the decision to interweave accounts of the show’s conception with auditions for its revival makes for a contrast that’s perhaps unavoidably unflattering for the latter. The original was a long-gestating masterwork of magical humanism, and the 2006 version is an attempt to honor and approximate the spirit of that model. A painstaking, organic creation based on the life stories of Broadway chorus lifers, A Chorus Line managed to retain individuality and authenticity from first to last in its depiction of a spectrum of neglected types. Bennett had recorded twelve hours of conversations with Broadway’s overlooked heroes—the chorus girls and boys that bounced from show to show and audition to audition—and devised a play that could showcase their stories. “I think you’re all interesting,” he told those gathered. “And I think there’s a show in that.” Some performers, like Baayork Lee and Donna McKechnie, played characters largely based upon themselves. Part of a long tradition of backstage musicals, A Chorus Line transcended the genre by turning it inside out: rather than melodrama in another guise, it sought a unique form that could best present its subjects, a form that emerged as a straight line over which the mess of life could stagger. It remains one of the great achievements of the American stage.

Finding a new crop of performers to interpret these finely etched roles for a Broadway revival may be a tall order, but not much taller than casting for any other beloved show. The greater burden rests with Every Little Step, as it tries to imply that these fresh-faced theater pros have stories as fascinating as the source characters. Filmmakers James D. Stern, a sometime Broadway producer, and Adam Del Deo clearly respect the lives of stage performers, but they struggle to articulate that respect, reaching instead for counterproductive cliched shots of dancers pulling on sweats and parkas, driving to rehearsal, and gratingly parroting powers of positive thinking. These are immensely talented, largely polished singers, dancers, and actors competing at the top of their craft (Bennett’s resilient heroes don’t stand a chance of winning spots on this chorus), but their pantomimed concerns and New York street-strolling make them seem no better than countless American Idol wannabes, each with a canned dream for the big break.

The popularity of “Idol” and other reality programs have flattened our understanding of competitions and casting, leaving us with empty, wrongheaded notions about popularity, favoritism, and random selection. Yes, it’s a cutthroat business, and election is always subjective, but here the judges really do know better, and they’re not exactly enduring William Hung. Too familiar tension-mounting cross-cutting aside (will it be the blonde or the brunette, the tap dancer or the ballet dancer, the aging beauty or the newcomer?), enough frank truths and odd particularities emerge in Every Little Step to make it a fascinating and often essential document about the preparation for and creation of live theater. After flurries of casting calls, cuts, and callbacks, which the filmmakers deftly reduce from hundreds of hours of footage, the film really hits its stride in the final call. Here the stakes are high and clear, and the pressures, anxieties, and subtle inter-sniping that besiege the finalists make for compelling voyeurism. “In order to get a job on Broadway,” says one of the evaluators before the final auditions, “You have to give an opening night finished performance.” Which turns out to be cruelly correct, despite the best efforts of director Bob Avian (who also co-choreographed the original production) to coach perfection out of sentimental but inferior favorites.

Illusions of open calls and undiscovered talent are belatedly if subtly shattered when final verdict phone calls are made to . . . talent agents (oh right, those guys) who in turn contact clients who then shriek into cell phones with versions of “I got it!” and avoid the trailing camera like pros. This likely wasn’t what Bennett had in mind when he started recording that night in 1973, but it’s still an interesting bit of business.