Status Update

By Adam Nayman

The Social Network

Directed by David Fincher, U.S., Sony Pictures

David Fincher’s The Social Network is bookended by sequences that take up the question of whether or not its protagonist—Facebook cofounder and barely postadolescent billionaire Mark Zuckerberg—is an asshole. That the verdicts come courtesy of a series of female observers is at once unusual in light of the film’s masculine thrust (all of the major characters are young men) and perfectly apposite considering its major underlying theme. Which, by the way, has less to do with the conception and consequences of social media than a different kind of complex closed circuit: the male ego.

Happily, The Social Network, freely (and brilliantly) adapted by The West Wing perp Aaron Sorkin from Ben Mezrich’s 2009 bestseller The Accidental Billionaires, frames this investigation in explicitly comic terms. Things are uptempo from that very first scene, which finds Zuckerberg talking himself right out of a relationship with his smart and pretty girlfriend Erica (Rooney Mara). Her supportive concern that her partner’s desire to get into the most prestigious Harvard “Finals Club” fraternity evaporates in the face of his galling, insistent condescension (“You’re going to come with me to parties and meet a lot of people you might not otherwise get to meet”).

What makes the scene so bracing—besides its breathtaking neo-screwball pace, managed by Fincher and editors Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall as a series of perfectly interspersed reverse-shot volleys—is how oblivious Mark remains to his own awfulness. Before leaving the table in a wounded huff—and thus leading her spurned boyfriend to write a vicious blog post about, among other things, her bra size, and then to create an even nastier Internet site that pits headshots of female Harvard students against one another in peer-voted online smackdowns—Erica asks Mark if he’d ever had any interest in taking up rowing. Eisenberg’s stricken expression—the only one he displays in the scene beyond the character’s default half-lidded smirk—cuts to the core of the prologue, and by extension, the film’s true subject. Feelings of inadequacy prompt outsized ambition; The Social Network imagines a young man’s violent remapping of virtual terrain as an attempt to impress a girl.

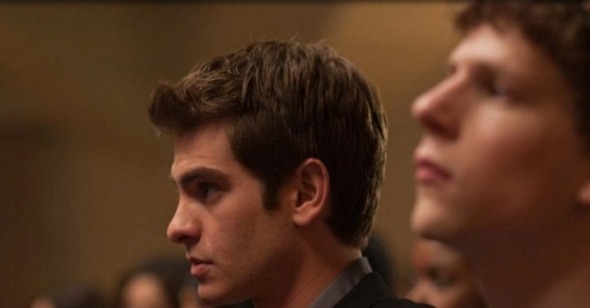

Revenge of the nerds, then, and The Social Network is replete with variations on the geek stereotype. Not just Zuckerberg, whose unofficial undergrad uniform of floppy sweatshirts and flip-flops signifies only a grudging willingness to leave his dorm room, but also his best friend/eventual multimillionaire complainant Eduardo Savarin (Andrew Garfield) and their circle of dorky peers, indelibly glimpsed crowded haplessly together at a Jewish campus group’s “Caribbean night.” It is Eduardo, who comes from money without acting like it, who reluctantly creates the “Facemash” algorithm that leads directly to Mark’s first, thoughtlessly misogynistic attempt at uniting his peers in front of their computers, and then indirectly to the creation of Facebook. An early sequence cross-cutting between a randy frat-house party—all hot girls, bumping beats and strip poker— and uninvited students of both genders indulging their resentment by playing cruel either-or games with those unwitting “Facemash” headshots crystallizes the disconnect between social networks.

In the other corner: the Winklevoss twins, Tyler and Cameron, hulking, perfectly coiffed alpha-male trust-fund strivers, who enlist Zuckerberg to create a “Harvard Connection” website only to get rooked when he spends the time (if not their money) devising his own, far more appealing, site. In Fincher’s lone (and smashingly successful) display of special effects mastery, both twins are played by a single actor: Armie Hammer (of Reaper non-fame). It’s a brilliant performance—Hammer nails both brothers’ disarming sincerity, which only serves to make their literally Olympian senses of self-entitlement (they plan to row for the U.S. team) that much funnier. The choice to double one performer is also a genius move on Fincher’s part. The surreal beer-goggle effect of these natty twin Goliaths manifests all of Mark’s every-nerd anxieties in the (flawless) flesh. Cameron and Tyler are living, breathing proof that he’s not tall enough, or rich enough, or handsome enough, or connected enough. (The Winklevosses also have their own pet nerd, memorably etched by Max Minghella; of all the actors in the film, Hammer and Minghella do the best with Sorkin’s characteristically rat-a-tat dialogue).

It thus seems like the natural order of things that Zuckerberg and the Winklevosses (what great names!) should become rivals: stymied at every attempt to exact unofficial retribution for their former collaborator’s insanely profitable bit of subterfuge (including a hilarious visit to the President of Harvard, who rabidly dispels each one of nicer-twin Taylor’s endearing notions about “Harvard gentlemen”), they decide to file a lawsuit. So does Eduardo, although for very different reasons, and so The Social Network unfolds with an elaborate (and still perfectly legible) nested-narrative structure, framing the 2003 beginnings of the story through testimony offered at a pair of deposition hearings. There’s plenty of sheer filmgoing delight in seeing and hearing the testimony echo and reverberate across time periods and locations in a series of deftly edited montages, but it’s equally true that this structure permits Fincher and Sorkin to indulge in a bit of nicely underplayed “what is truth?” philosophizing: even if the film doesn’t do too much with the clashing points of view, it never lets us forget that they’re in a state of flux.

Which is why, as The Social Network charges along—and it really does move like a shot, especially compared to the lugubrious Benjamin Button—Eduardo emerges as, if not its hero, then definitely its locus of viewer sympathy. If the Winklevosses’ efforts to sue Mark for a piece of his empire suggest elites trying to horn in on a former subordinate’s good fortune—and exist in the film more as comic relief than anything else—Eduardo’s arc is more relatable and affecting. It’s clear that he idolizes his pal despite the fact that Mark rarely acknowledges his friendship and in fact actively resents his successes (when Eduardo reports that he’s pledging for a prestigious fraternity, he’s informed that it’s great that he’s gotten so far, and not to be disappointed when he’s cut at a later date). If anything, Mark treats Eduardo with the same unemphatic disdain as he did Erica. The treatment gets worse once Napster creator Sean Parker (a truly inspired performance by Justin Timberlake, wittily cast as a the man who would destroy the record industry) gets wind of their upstart operation and his hooks in the ascendant curly-haired media emperor. A former pariah himself, only now armed with money and status, Parker is a cautionary tale who Mark sees as a mentor: rarely has male seduction been so convincingly played. Sean lures his new friend to California with (wholly verifiable) tales of Silicon Valley bacchanalia and tries to edge Eduardo out of the picture—a hetero love-triangle underpinned by real feelings of lust (for money/status/friendship) and betrayal, and it’s so much more sophisticated than the pummeling psycho-dynamics of Fight Club that it makes that earlier film look even more juvenile than a decade's worth of hindsight has already rendered it.

In some ways, it’s hard to believe that The Social Network was made by David Fincher, a guy noted neither for fleetness of pace nor a light touch. And yet here he has made a quick-witted borderline-screwball comedy. The cruelty endemic to so much of the director’s work—the art-directed sadism of Se7en; the audience-suckering artifice of The Game; the glib counterculture pretenses of Fight Club—is present, but it’s attributable to the characters rather than the filmmaker, and even then, Fincher is careful not to slip into American Psycho Jr. mode, allowing the kids their humanity even as they seek to submerge it. He’s also reigned in his stylistic excesses. Even a borderline great film like Zodiac was marked (if not marred) by the sense of a director showing off his control over his art (like the time-lapse sequence of the Trans-America building being constructed), while a sincere but obvious misfire like The Curious Case of Benjamin Button never managed to transcend its CGI gimmickry and blossom as drama (although the fault lay as much with screenwriter Eric Roth’s Gumpian gambits as any of Fincher's desultory directorial choices).

With that in mind, all of the environments in The Social Network are striking: the rich, brown interiors of the Harvard faculty buildings and campus pubs; the dull Valley sunlight of Facebook’s West Coast headquarters (a rented house in a perpetual state of all-night kegger-y); the anodyne drabness of Mark’s first big-boy office (which doubles as the primal scene of his betrayal of Eduardo, a phenomenally acted scene of beta-male rage). And yet one never gets the sense that Fincher is anything but locked into the demands of his script, and his story. Similarly, Sorkin’s pinball rhythms have generally struck me (and a lot of other people) as cloying at best (Sports Night was alright), but there’s something right about having these snot-nosed masters of an ever-expanding artificial universe speak in such a terse, aggressive argot. The effect is not unlike hearing characters reading out rapid-fire text/e-mail exchanges, except that, being Harvard types, they do so with the spellcheck engaged.

There are elements that either don’t quite work or raise red flags: for instance, it’s hard to tell if the distaff characters—including, besides Erica, a sympathetic lawyer played by Rashida Jones and Eduardo’s psycho-hose-beast Asian girlfriend, whose two major contributions to the story are a bout of bathroom fellatio and a Fatal Attraction moment involving a lighter and a silk scarf—are so thinly sketched because of the film’s preoccupation with male psychology or because Fincher and Sorkin don’t really have the imagination to take them further. (Maybe it’s a bit of both). It’s also arguable that Sorkin hits his themes a little too hard in the final moments, which, as mentioned before, dovetail tightly with the opening ones. In a way, the finale is a full-on replay of the first scene, with Erica present but mute and Zuckerberg eventually left to ponder his own isolation. It’s a compliment to Eisenberg (so good last year as a much more relatable teen-on-the-verge in Adventureland) that we don’t feel much differently about Mark Zuckerberg in the final scene of a two-hour movie than we did in the first—which is not the same as saying that we don’t understand him differently.

Destined for movie-of-the-moment status (and possibly IMDb/AMPAS canonization shortly thereafter), The Social Network is surely clear-eyed about what motivates so many residents of the Western world to live their lives online—not as an escape from the divisions and disappointments of corporeal existence, but rather a safe, privately experienced extension of same. But as an unsentimental coming-of-age fable that pivots on whether becoming asshole is a choice or an accident—and whether there’s any difference between acting and being—it’s more than a simple status update. I dare say that it feels timeless.