The Age of Innocence

By Kristi Mitsuda

Somersault

Dir. Cate Shortland, Australia, Magnolia Pictures

In the midst of one hazy, drunken night in Cate Shortland’s Somersault, Joe (Sam Worthington), attempting to describe a girl with whom he’s recently become involved, says, “You know when you were a kid, did your mum ever used to spray perfume in the air, and sort of walk through it?” His neighbor, Richard (Erik Thomson), remembers that she did. “She’s like that,” Joe explains. “Like perfume?” asks the other. “No . . . see, when you leave, you still feel her on your skin.” A similar thing could be said of this Australian writer-director’s captivating debut feature: though I left the screening room (it played at the New Directors/New Films Festival) unsure of my feelings for it, over a year later, it remains with me.

Taking as her focus a teenage girl’s sexuality and the unconsciously self-destructive tendencies concomitant during that early period of experimentation, Shortland—in a visually delirious style to match—explores a topic often untouched in film. Hard-partying and ready to hook up with any boy who pays her the slightest amount of attention, Heidi (inhabited with breathtaking awareness by Abbie Cornish) possesses a relentless sexuality apparently without boundaries and a dangerously impulsive nature, a combination quickly set up within the first 15 minutes of Somersault: Caught seducing her mother’s boyfriend, she takes off without warning for a ski resort named Jindabyne.

The unusual setting of a wintry landscape stands in stark contrast to the usual cinematic description of Australia as a place solely defined by sun-baked expanses, and the inward-turning nature of the season establishes an appropriately somber and reflective tone to underscore the proceedings. In this new locale, Heidi uses her beauty as we suspect she often has in the past—to score free drinks, to help her job-seeking chances (she pretends a store-owner’s tag is sticking out of his sweater as a pretext to touch him), to secure a place to stay for the night. She throws out pick-up lines off-handedly, in a way both transparent and disarming. But underneath the minute manipulations resides a core of innocence: the frequency of this 16-year-old’s casual encounters reveals the loneliness and desperation so specific to that tangled period wherein emotional and sexual maturity have yet to coincide. That agonizingly recognizable phase (and we’ve all been there, haven’t we?) when you get blind drunk and take someone home irregardless of consequences, the unspoken underlying wish being to feel close to another person, to feel loved. This is what Heidi clearly craves, and Cornish’s feelingly subdued performance captures with minimal dialogue the nuances of this confusion of sex and intimacy.

Broken by a harsh realization one moment (the boy she just slept with has a girlfriend in Sydney, for instance), only to be quickly renewed in her faith that the next boy she meets will be genuine, Heidi has a resilient fragility about her, and this wide-eyed openness sets her apart from others, compounding her isolation: a child-like habit of taking pleasure in the smallest of details mark her as woefully unhip to many of the locals. We see this strangeness reflected back to her in introductory scenes with fellow BP worker Bianca (Hollie Andrew), who appears visibly annoyed by Heidi’s unusual manner, the way she buys red gloves and then gleefully puts them on immediately, the tag still binding the pair together as she stretches out her hands for the other to cut the cord. We later watch Heidi wander around the fields near the Siesta Motel where she’s renting a flat in the back, clapping a child’s hand-game by herself, the red gloves twin points of color in an otherwise bleak vista.

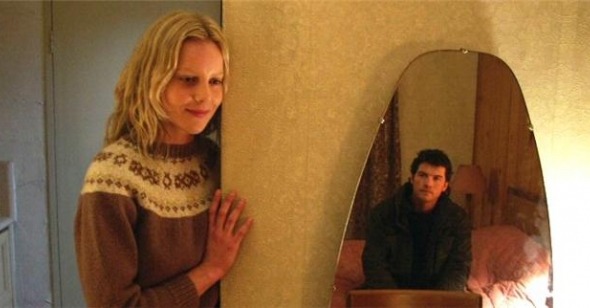

When she meets Joe, we know they will share an implicit understanding. It’s in that first look: he appears mesmerized by her as she gazes deeply into a glass of beer, taken by the bubbles. Defined by a strong tactile connection—each is constantly shown picking up and examining objects—their similar sensibilities are illustrated via frequently rhyming images: Heidi stares at crisp, dry leaves rustling on the ground; Joe examines the shadow his hand casts over a pond full of fish; she dons a pair of abandoned red goggles and spins around in a newly violet universe; he picks up a red decorative glass in Richard’s house and holds it up to the light, the bare branches of trees outside visible through its sides. Seemingly both washed-out and saturated at the same time, the lushness of the cinematography by Robert Humphreys pulls out the textures in these compositions, as does Shortland’s periodic use of slow-motion. And a gorgeously selective use of focus creates a vividly impressionistic point-of-view perfectly illustrative of the sensorial wonder Heidi and Joe share.

But Somersault is no simple, uplifting journey, the tale of two lost souls who find and heal one another. Rather, it’s about the intersection of a pair of emotionally confused people, each fucked-up in their own private ways for any number of reasons to which we’re not privy, and how they subtly affect one another. Since we come into their lives with no clear idea of their personal histories, we don’t fully grasp their motivations. We sense Somersault means to chart an awakening of sorts for both characters, but the progression remains elusive, unresolved, continual, in ways more true-to-life than the typical coming-of-age movie. Uneven at times and a tad pretentious in a fashion typical of first features, you nonetheless easily excuse Shortland’s occasional misstep, so beautifully has she wrought an epochal period in the experience of female sexuality at last given serious and sensitive representation.