by Kevin B. Lee

La Haine

Dir. Matthieu Kassovitz, France, 1995

Criterion’s lavish double-disc treatment of La Haine gives ample testimony to the film’s importance, not only to recent French cinema but also to contemporary French society. The film, an eye-opening look at the lives of angry youths in the French slums (banlieues), caused a sensation upon its release. Following a fateful day in the life of three friends—an Arab Muslim (Said Taghmaoui), a North African (Hubert Kounde), and a Jew (Vincent Cassel)—that ends in police brutality, La Haine stood out like a sore thumb among the many high-profile productions focused on the upper and middle-classes. Shot in black-and-white and squarely aligned with its working class minority characters, the film improbably garnered 29-year old Matthieu Kassovitz the directing award at Cannes, and even more improbably, the best picture prize at the Césars.

Kassovitz hasn’t yet matched his early success as a director (his most recent film was Gothika), and La Haine did not inspire a movement towards more minority-focused French films, as many had hoped. (Ironically, Kassovitz had a major acting role in Amélie, one of the most gentrified depictions of France in recent memory.) However, on its tenth anniversary, the film returned to the spotlight as riots erupted throughout the banlieues in the fall of 2005. On his personal blog Kassovitz lambasted then-Minister of the Interior Nicholas Sarkozy for making polarizing, vaguely racist remarks in referring to the rioters as “scum.” Remarkably, Sarkozy deemed Kassovitz and his remarks important enough to offer a point-by-point rebuttal. Now that Sarkozy is the newly elected President of France, it remains to be seen whether more violence will erupt in reaction to his conservative stance towards the communities depicted in La Haine.

If it seems that I’m writing more about the social context of the film than the film itself, perhaps it is because the film’s stature is based largely on its status as a social document, something the extras of the Criterion DVD make plain. There’s a half-hour of interviews with sociologists on the plight of the banlieues, and the feature-length documentary about the legacy of La Haine opens with news footage of the banlieue riots that inspired the film. This mirrors the opening of the film itself, which takes footage from those same riots; combined with the timeless quality of the black-and-white cinematography, the archival footage establishes a feeling of documentary authenticity.

Establishing this authenticity proves to be critical for La Haine, as upon closer inspection the film repeatedly reveals its artifice. Stylistically, Kassovitz employs numerous tracking shots and elaborately staged long takes that lend the film a perpetually busy feeling. Often the real time unfolding of events adds to the realism, while other times the movements call attention to themselves—homages to the hyperkinetic street cinema of Mean Streets and Do the Right Thing. Along these lines, the film might seem like a French derivative of those films as well as John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood; but again, within its native context this was a groundbreaking statement against the upper-class filmmaking that has long dominated French cinema.

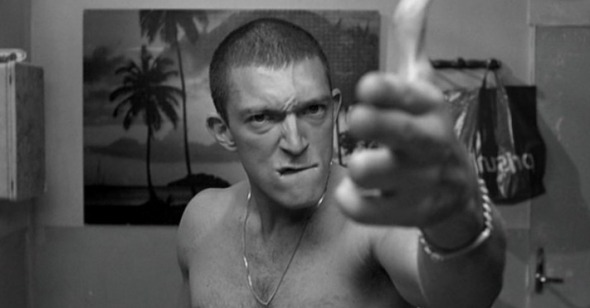

But Kassovitz doesn’t merely borrow the look of American street films; he makes something singular. From scene to scene he lenses and frames his figures so that they stand out against their stark surroundings, interior or exterior. The look of the movie is critical because the film’s narrative is full of drift and dead ends: endless profanity-laced dialogues that sound like Tarantino without the wit, anecdotes that lead nowhere, and plans that go astray. Throughout all these instances, the camera moves like a fourth character, placing us alongside this threesome, so that their juvenile blathering achieves a kind of intimacy, inviting and accepting us in their stand against the world. The three lead actors—the impressionable Taghmaoui, the dignified Kounde, and the manic Cassel—also go a long way in winning our empathy for these delinquents. Some have expressed doubt over the plausibility of friendship between the multicultural leads—especially between a Jew and a Muslim. Yet Kassovitz uses them to exemplify the possibility of social progressiveness rather than reflect reality.

The DVD video transfer is up to Criterion’s impeccable standards, and the supplementary materials give the film its due. In addition to the two documentaries, there is footage taken from production as well as preproduction, when Kassovitz and his three leads stayed for months in the neighborhood where they would eventually film. Jodie Foster, whose company distributed the film in the U.S., gives a compelling introduction, and Kassovitz provides one of the better commentary tracks that I’ve heard: entertaining, informative and candid. For one thing, there’s more Sarkozy-bashing, portending that sadly, this film’s social relevance may continue for the foreseeable future.