When No One Is Returning:

The Films of Karel Vachek

by Alice Lovejoy

The Czech Republic’s European Union presidency started with a bang in January with the controversy over David Černý’s sculpture “Entropa,” installed in the European Parliament and featuring Bulgaria as a Turkish toilet, Sweden as an Ikea box, and France permanently on strike. And before the country’s six months in the Brussels spotlight are up, the work of another of its artistic provocateurs, documentarian Karel Vachek, will be on view in the United States, in retrospectives of his documentaries at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Made between 1963 (the very beginning of the Prague Spring) and 2006 (two years after the Czech Republic’s accession to the EU), the films offer a wide-ranging chronicle of forty years of political and social change in one corner of Central Europe, refracted through the director’s trademark hybrid of cinema vérité, performance, and philosophy.

Vachek has been in the States twice before—once with a retrospective of his long-format documentaries of the Nineties in 2002, and once twenty years earlier when, banned from filmmaking in his home country, he moved to Jersey City. After returning to Czechoslovakia in 1984, Vachek tended high-pressure boilers and drove delivery trucks until being allowed to work as a filmmaker again after the collapse of the communist government in1989. “I leave when no one is leaving and I return when no one is returning, and I think that that is my fundamental life situation,” he says in his 2004 book The Theory of Matter.

The hubris of this title is partly serious, partly performative—an attitude reflected in all of Vachek’s work, which extends beyond his films and book to performance, painting, and pedagogy. All of these projects attack a central philosophical issue, one that Vachek refers to at times as “inner laughter,” at times as “centeredness,” and has to do with a particular way of living one’s life—the secret of which only a few wise individuals have understood. The gravity of this issue is balanced by a heavy dose of levity: one of Vachek’s key “centered” individuals is Mexican-American singer and guitarist Trini Lopez.

It’s never clear if Vachek himself identifies as “centered,” but like these figures, he does exactly what his quote suggests, “leaving when no one is leaving and returning when no one is returning,” remaining deliberately out of step with the world around him. His films are epically long, ranging from roughly two and a half hours to over four hours. They are expensive: all are shot on 35mm, and until recently, Vachek edited on a flatbed, preferring the tactility of celluloid to the abstraction of online editing. The films, of course, are not a natural fit in exhibition spaces or schedules. And when, this fall, the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival screened all of Vachek’s recent documentaries back to back in an all-day performance at which viewers came and went, the format seemed appropriate for the films’ lush, enveloping, wide-angle images of the world.

For Vachek, “being out of step” is a role as much as a mode of filmmaking. Like Michael Moore (whose desire for provocation he shares) or Ross McElwee (like Vachek at times a picaresque figure), the director is a central presence in all of his films, in deep conversation (often argument) with his subjects, or lecturing or performing his interpretations of philosophy and history. His most recent film, Záviš, the Prince of Pornofolk Under the Influence of Griffith’s Intolerance and Tati’s Mr. Hulot’s Holiday or The Rise and Fall of Czechoslovakia (1918–1992), takes this to an extreme degree: the film is a monologue of sorts; a treatise on the director’s philosophy, filmed during a lecture to his students at FAMU, the Prague Film Academy. This soliloquy is interspersed with scenes from contemporary Czech politics, society, and everyday life that deal with the absurd, whether in the form of a corporate-sponsored tomato battle; an awkward, canned funeral for a beloved pet; or corruption at the highest levels of government.

An evolution to this kind of absurdity was the hallmark of Vachek’s previous documentaries, a set of four “film novels” collectively titled the “Little Capitalist Tetralogy.” These films—New Hyperion or Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood (1992); What Is to Be Done? A Journey from Prague to Český Krumlov or How I Formed a New Government (1997); Bohemia Docta or The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart (Divine Comedy) (2000); and Who Will Watch the Watchman? Dalibor or The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2003)—moved from the optimistic, vérité-style New Hyperion, a portrait of Czechoslovakia in the carnivalesque period of 1989, to Dalibor, whose characters (most of them “centered,” but some of them not) are gathered in Prague’s National Theatre—a bunker against the corrupt, valueless world pictured in Záviš; its stage a metaphor for the film’s own theatricality. Indeed, and ironically, it is in great works of fiction—the novels, operas, and films that his film’s titles reference—that these documentaries seem to see real value, both cultural and political.

The disillusionment with the contemporary Czech state of affairs in Dalibor and Záviš is nothing new: Vachek’s work from the 1960s, before he was banned from filmmaking in the aftermath of the Warsaw Pact invasion, is similarly cynical. He points out the absurdity in, for instance, the Czechoslovak communist government’s support of “folk culture” in Moravian Hellas (1963)—a film inspired to no small degree by Surrealism (Czechoslovak and foreign), and, according to scholar Martin Ĺ voma, personally banned by then-president AntonĂn NovotnĂ˝. Indeed, the sole film in his oeuvre that betrays a real belief in a political system is the vĂ©ritĂ© Elective Affinities (1968), a rare behind-the-scenes chronicle of the Czechoslovak presidential elections of 1968, just months before the invasion, and a Czechoslovak Primary of sorts.

It was in these years—the height of the Prague Spring—that Vachek emerged, studying at FAMU at the same time as the well-known fiction filmmakers of the Czechoslovak New Wave (Jan NÄ›mec, Jiřà Menzel, and others). And for the brief moment that he was allowed to make films, he was the New Wave’s most unique and promising presence in nonfiction, synthesizing the world movement in vĂ©ritĂ© with his own idiosyncratic voice. Today, as documentary is emerging as one of the most important aspects of cinema in East Central Europe, Vachek is a key figure once again. As head of the documentary department at FAMU, he is training a new new wave of filmmakers, whose political world is not defined by socialism (or even, really, postsocialism), but rather by the European Union, NATO, and globalization (Czech Dream co-directors VĂt Klusák and Filip Remunda are two of his former students). And alongside them, the old master continues to make films, adding to the chronicle of Czech history, politics, and society mapped out in the nearly twenty hours of his documentaries to date.

Karel Vachek’s films screen in the series “Karel Vachek: Poet Provocateur” at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, CA, from Sunday May 31 to Sunday June 28, with the director in person on June 21 and 24. From June 6 – 27, the series “The Film Novels of Karel Vachek” screens at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, with the director in person June 27.

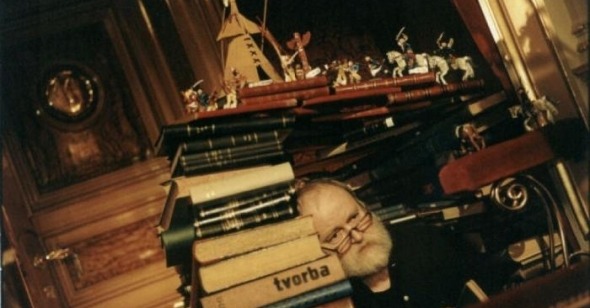

Above: photo from Dalibor.