Full Moon Fever

By Danielle McCarthy

In the Shadow of the Moon

Dir. David Sington, U.K., ThinkFilm

In R.E.M.’s 1992 ode to Andy Kaufman, “Man on the Moon,” Michael Stipe sings, “If you believed they put a man on the moon . . . if you believe there’s nothing up my sleeve, then nothing is cool.” Stipe is essentially referring to the power of dreams, as well as their capability to fail us—and the cynicism that can inspire. The Apollo space program, and the resultant landing of a human being on the surface of the moon, has for years inspired both awe and doubt: looking back nearly 40 years on, it’s at best considered a quaint oddity of the turbulent 1960s and at worst a hoax manufactured to stave off America’s imaginary Russian threat. With its glory days long past, NASA is better known now for its public relations fiascos—including violent love triangles, astronaut diaper abuses, alleged on-shuttle drinking, and, of course, the loss of Challenger, Columbia, and the fourteen astronauts onboard. So the timing couldn’t be better for British director David Sington’s earnest Apollo documentary, In the Shadow of the Moon, a truly giddy moviegoing experience that approaches, as one astronaut describes, an “ecstasy” in its chronicling of one of human history’s most fascinating and daring endeavors.

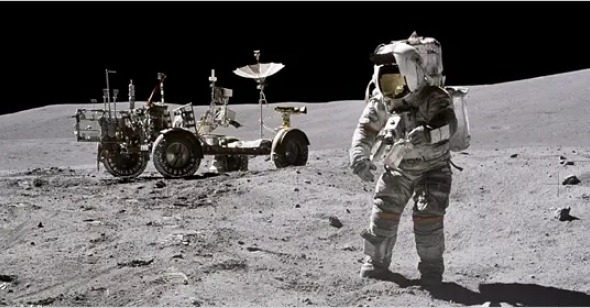

I would be remiss to not admit my own biases toward the subject matter. I grew up on the Space Coast, and it was a common occurrence for me to see rockets launch into the bright Florida sky. My insistent begging to go to Space Camp was brushed off by my parents as the stuff of typical childhood dreams. All these years later I still consider myself a “space nerd,” but one does not need to worship at the altar of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to be swept up in the wonderstruck awe on display in In the Shadow of the Moon. Wisely, Sington narrows his focus to the recollections of the men who ventured to the moon, allowing that mix of macho posturing and inhuman fearlessness known as “the right stuff” to intermingle with the astronauts’ refreshingly frank vulnerability—by now, the astronaut hero mantle is well beyond tarnished, but Sington captures these men, the select few chosen to journey from the earth to the moon, at their most open, humane, and funny. Clearly, these were incredibly talented, intelligent, and driven individuals, but Sington is more concerned with the wondrous imagination at work behind Apollo than the bravado that Tom Wolfe detailed (and chided) so famously in The Right Stuff. In fact, barely any attention is paid to the political motivations behind the Apollo program; the film manages to capture patriotism without politics, which nowadays seems almost as alien as the surface of the moon.

Of course, Sington is hardly the first to explore the experiences of the Apollo astronauts. Al Reinert’s more cerebral 1989 take, For All Mankind, utilized NASA’s wealth of archival footage and framed it around audio interviews that explored the effect the journey had on the 24 men who made the moon shot. Reinert’s film captured the abstract beauty of the Apollo missions, as Brian Eno’s gorgeous music from Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks single-handedly changed the soundtrack of space travel. While Sington’s approach is much more straightforward, his goal is to capture the same wonder as in For All Mankind. Political motivations aside (the moon shot never would have happened if it wasn’t for a little Russian satellite named Sputnik), the Apollo program is simply one of the most outrageous ideas ever implemented, a wild and dangerous proposition that captured the imagination of the world and changed the way we perceive our universe. However, what is even more outrageous is how little effect that gained perception has had on the general population decades later. Like a passing fad, the Apollo program wore out its welcome with the public, and without the element of competition there was little reason to continue spending tremendous amounts of money returning to the moon without a concrete benefit to everyday Earth dwellers.

While Sington’s film addresses the gripes about the relative value of the lunar missions to the rest of humanity, his attempts to validate Apollo’s purpose by sloppily attaching a commentary near the end on Earth’s environmental crisis probably won’t help to convince the skeptics. Considering how difficult it is to elucidate the expeditions’ benefits to humankind beyond a greater appreciation for Earth’s fragility and uniqueness, there’s been little new interest sparked in the currently directionless space program. What is remarkable about Apollo is that it shows what we are capable of as a nation; a patriotic assertion already in steady decline during those heady days. In its own sincere (and refreshingly uncool) way, In the Shadow of the Moon captures an almost naïve belief in the can-do American spirit. As astronaut Jim Lovell explains, “It was a time when we made bold moves.” The public now seems unmoved by the sheer audacity of the Apollo experiment. And while the White House recently ordered a new moon program designed to send humans back to the moon by 2018, could such a risky endeavor ever regain the confidence or imaginations of the taxpaying public? Sington leaves the question open-ended, simply stating, “We have yet to return to the moon.”

In the Shadow of the Moon mostly sticks to the greatest hits—the Apollo 8 orbit around the moon on Christmas Eve, the first landing of Apollo 11, the near tragedy of Apollo 13—with the remaining missions generally glossed over. For the hardcode space enthusiasts, the lack of attention paid to each individual mission may be disappointing, but for the neophytes it will provide an excellent overview of the program. Sington also adds pop-cultural references, including an effective sequence paralleling the drug culture of the 1960s to the far-out idea of space travel. And during the closing credits, the director also gives the astronauts a chance to defend themselves against the skeptics with humorous queries like, “If we faked it, why did we fake it nine times?” (Although I wish Sington would have included the footage of a recent incident in which Buzz Aldrin decked a conspiracy theorist who asked Buzz to swear on a Bible that he indeed walked on the moon.)

Overall, the tone of the film and Sington’s interviews is one of wonder (these days, a nice antidote to “shock and awe”). As Apollo 12 astronaut Al Bean notes after his return to Earth, he would go out to shopping malls and just watch the people go by and think, “how lucky we all are to be here.” It’s impossible not to feel a contact high from just hearing these extraordinary stories: indeed, if there was ever a reason behind the outlandish dream of Apollo it would be a greater appreciation for the unique planet we all inhabit, for better or worse. While most people prefer the conspiracy theorist version of events (as Stipe claims, “nothing is cool” if you believe man walked on the moon), the incredibly true story of Apollo gives hope to what we are capable of, and ultimately tells us that what really matters is much closer to home than we could ever envision.