Fatal Attraction

By Justin Stewart

Gone Baby Gone

Dir. Ben Affleck, U.S., Miramax

It feels good to be an apologist. Once the decision has been made to take someone on as your charge, cumbersome critical faculties can be relaxed—there's no longer any need to choose sides. Most freeing of all is that it doesn't really matter who you defend. Thinking back to last night's party, hearing yourself eloquently championing Matthew McConaughey or whoever, you might even convince yourself, and realize the arbitrariness of your cherished "opinions." It's like baseball fandom—when you like a player as a rookie, you don't throw away the cards from all of his slump years, you protect and sleeve them like the rest.

Ben Affleck can do little wrong by me, but it's difficult to say why. A resume with lowlights as low as Reindeer Games, Pearl Harbor, and Gigli and highlights as modest as Good Will Hunting and Hollywoodland can't be the answer. The whole "sexiest man alive"/Bennifer phase was pretty irritating, and came as something of a surprise to those of us who were first aware of Affleck as Chasing Amy’s chunky loser-in-love Holden McNeil. His self-deprecation in the Silent Bob movie (I refuse to type the title) and on shows like Dinner for Five helped a little, though it still wasn't clear how far he was stretching himself while basically slumming it. His appeal to me might be something as simple as his retiring laugh or aura of solid dude-ness; I can only chalk it up to the mysteries of apologia.

Gone Baby Gone, Affleck's first directorial effort (outside of a 1993 short,

another title I refuse to type), is much like his performances: plain, a little disappointing, but still worthwhile. He was smart to make a Boston movie first; he seems unsure of what to do with the camera during the several wordy, morally heavy scenes that weigh the movie down, but there's always a definite sense of location, an authenticity to the gray South Boston streets that Affleck nails. His job is aided by the specific heavy plotting of the screenplay he wrote with Aaron Stockard, based on the Dennis Lehane novel. This anal retentive attention to plot mechanics safeguards against potential rookie indulgences; when Affleck can indulge, he's only partly successful, as in the troubling long take that closes the film.

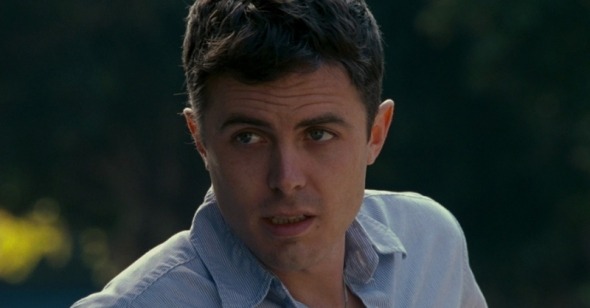

Casey Affleck is Patrick Kenzie, one half of a private detective team, along with his girlfriend Angie (Michelle Monaghan), hired by the mother of a kidnapped four-year-old. The real police on the case, hard-nosed detective Bressant (Ed Harris) and Crimes Against Children unit head Doyle (Morgan Freeman) initially chafe at the freelance intrusion, but eventually welcome the local lowlife contacts that Kenzie provides. The closer the detectives get to the truth, the further they get from clarity. In proper crime novel tradition, each layer pulled back reveals something that was hidden for a damn good reason.

Kenzie is a fresh-mouthed upstart, "young-looking for his age" of 31, and an irritant to the seasoned fifty and sixty–something pros. So the casting of the director's young-looking, skinny brother is appropriate. (As in The Departed, we're expected to swallow that skinny guys can beat the shit out of gigantic thugs. But this is the medium that made a tough guy out of a 5'5" James Cagney.) Casey is a lightweight among heavyweights Harris and Freeman in both physical presence and acting ability. In moral terms, Kenzie grows as the cops shrink, but Casey still holds his own. Freeman phones in the usual; that's nothing to sniff at and his gravitas saves a final endurance-testing twist. Not much is asked of Monaghan outside of decoration, and she dutifully provides it. If her character made a large mark on the novel, only the faint outline is felt here.

While it's not entirely fair to hold Gone Baby Gone up to the standards of a series like The Wire, its pedigree forces the issue. Lehane has written episodes for the Baltimore epic, and two actors (Amy Ryan and Michael K. Williams) have roles in both. Without the luxury of television's patience, a film must take shortcuts with a novel adaptation. That's fine—it's just that Affleck's shorthand can be particularly crude. As mentioned, his sense of place can't be faulted but you'd think his slum denizens wouldn't be quite so cartoonishly portrayed. Mostly filled by neighborhood non-actors, the bit and local color parts are merely horror-show ornamentation conveying a Deliverance-like descent into terror by clean-cut Casey and his pretty, button-nosed partner. The film's most sensationalistic (and groan-inducing) set piece features a cocaine-addicted old couple living in a garish hovel with their retarded man-boy son—exploitation to the extreme (did I mention that the wife is obese?) that could be fun if you weren't later asked to invest real feeling in the movie's big question, if a mother always deserves custody of a child. It's an identity crisis—Affleck can't decide if he's trying to be the measuring, empathetic Clint Eastwood of Mystic River, or Eli Roth.

George Pelecanos, another crime novelist and Wire writer, recently told the New Yorker, "If it's not about something more than the mystery, the thriller part, I'm not going to do it. Life's too short." Dennis Lehane evidently agrees, and with Gone Baby Gone, it's clear that Affleck does, too. It's when the movie reaches for this "something more" that it stumbles. Affleck doesn't have the power for it yet, a fact underlined by the reliance on Harry Gregson-Williams' drippy, hand-holding original music. It's still an auspicious entree, make no mistake—this is no Albino Alligator vanity curio. My main complaint is having to criticize Affleck at all. I'll now happily return to blind devotion.