Bob and Weave

by Michael Joshua Rowin

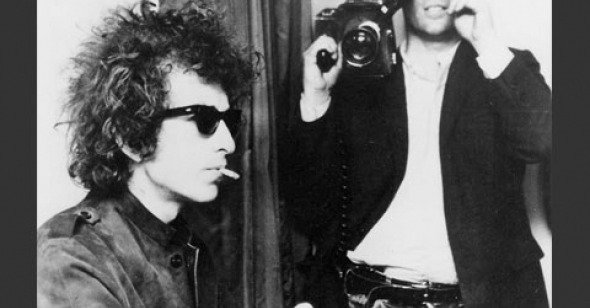

Dont Look Back

Dir. D.A. Pennebaker, U.S., 1967, Pennebaker Hegedus Films

D.A. Pennebaker’s groundbreaking 1967 Bob Dylan documentary Dont Look Back begins with a calculated sale: the two-and-a-half minute promotional film for Dylan’s first Billboard-landing single and electric rock anthem, “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” As one of the first predecessors to the music video it’s still a stunner, more Jean-Luc Godard than Dick Clark—committed to crossing over to the pop charts on his own terms, Dylan used the clip to spotlight his hip persona, certainly, but also to call direct attention to his language by nonchalantly holding up and discarding a series of cue cards containing fragments of the absurdist slang of “Subterranean.” Such simplicity, and what a statement! Dylan was so far ahead of the game in ’65 that he already understood the best way to undermine any “natural” relationships between sound, image and performer—long before the ubiquity of music videos and the complicated intersections between art, performance, and commerce they would inherently embody and exacerbate. The “Subterranean” clip thus becomes a semiotic explosion, dicing Dylan’s lyrics into contradictions (“11 dollar bills” on the soundtrack becomes “20” on a card), awkwardly isolated blocks (“head put,” “bed, but”), commentary (accompanying “look out, kid” on the soundtrack: “dig yourself”), silly puns (“suckcess”), accents (“pawking metaws”), and seditious shorthand (“leaders ? ? ?”), all as Dylan falls behind or races ahead of the words playing over him and to the point where the song goes beyond radical, nonsensical rave-up (but man, does it scorch!) to become a thing tenuously attached to its own intended meanings, literal and otherwise, as well as the artist who means them.

And that’s what Dylan would do throughout his career: stand in asynchronous affiliation to the words he was forced to defend, explain, detract, and represent. Pennebaker’s great achievement in Dont Look Back was in picking up on Dylan’s turbulent relationship with the language through which he both expressed and concealed himself, and, against conventional cinematic wisdom, in focusing on that relationship rather than simply “capturing” Dylan’s music. After the “Subterranean” clip and a truncated live performance of “All I Really Want to Do” (unseen but heard over the opening credits) there won’t be too many Dylan tunes in the film. We’re offered instead intimate yet officially sanctioned glimpses of Dylan the road warrior, making his way through England on the wave of his mainstream breakthrough a year or so before the semi-contrived “backlash” against his move to electric rock that would follow him through a later, more notorious, jaunt across the island.

The growing strain between Dylan and his audience—and, ultimately, the makings of the Dylan myth of reinvention and confrontation—can be clearly witnessed in Dont Look Back. Some of the film’s most iconic scenes involve Dylan in a kind of antagonistic dance with reporters and critics, sarcastically evading their questions or else derisively challenging their journalistic authority. “What is your real message?” a female reporter with a highfalutin British accent asks in a query put to Dylan upon touching down in London. Other gems: “Do you think a lot of the young people who buy your records understand a single word of what you’re singing?” “Would you say that you care about people particularly?” “You sound angry in your songs. Are you protesting against certain things that you’re angry about?” How would you react if you had to deal with an obligatory, daily grind of cultural translators demanding immediate, literal interpretations of your own work? (Dylan’s response, by the way, to the first question: “Keep a good head and always carry a light bulb.”)

“I mean, I accept everything, I accept this,” Dylan confesses at one moment when speaking about the press crush to a reporter, “Because it’s here, it’s real, it exists just as much as the buses outside exist. I mean, I can’t turn myself off to it because, you know, if I try to fight it I’m just gonna end up going insane faster than I eventually will go insane.” But does he accept it? Scenes of Dylan dressing down a Time scribe with scathing condescension (“Are you gonna see the concert tonight? Are you gonna hear it? OK, you hear and see it, and it’s gonna happen fast”), chewing out a young student trying to gain approbation (“If I go to interview Alan and his mob I don’t think they could care less about me.” “Haven’t you ever stopped to wonder why?”), or proving himself big fish to Donovan in a late night, guitar-strumming showdown, provide a plethora of evidence that Dylan responded to the pressure of his mounting fame with stubborn, near juvenile hostility. It’s remarkable how often I hear people make the same comment about Dylan in this film: “What an asshole!” Part of what makes Dont Look Back so incredible is that it might be the first public record of a celebrity openly, and with full knowledge of how his behavior might be received, acting like a complete jerk even when a camera is right there documenting his every movement for the world.

If Dylan, constantly called upon to explain himself explaining himself, gets put in a corner only to slip away by sheer force of personality—thus his retreat into or embrace of bitter enmity—Pennebaker calmly looks on. Call it direct cinema, call it vérité—nothing like it was ever before employed to film a famous musician “backstage” reveling in “down time.” A new demand at the time called for the replacement of slick, production-concealing pop product with something raw, something that would allow the fan or consumer greater access, or else the illusion of access, into the star’s world, and Pennebaker was there to provide it. One can understand the link Todd Haynes established in I’m Not There between the early Sixties Fellini films, with their carvinalesque arrangements of celebrity life as experienced by an overwhelmed participant/observer, and the distance Pennebaker collapsed between audience and subject while still retaining a detached attitude via grainy, handheld 16 mm. But Haynes’s well-intentioned mistake was to marry the first person subjectivity of 8 ½ to reenactments from Dont Look Back, resulting in surrealist kitsch, a failed mash-up of Dylan’s psychedelic poetry (though Haynes is so literal as to prove inept at psychedelia—a reference to Dylan’s stream-of-consciousness novel Tarantula, for example, is referenced as . . . a background-projected tarantula) with exaggerated, hollowed-out incidents culled from Dylan lore, each canceling the other out. Pennebaker positions himself at a nonjudgmental, arms-length remove that makes Dylan the inscrutable yet recognizable personage Haynes can only hint at in the Jude Quinn segments of I’m Not There. If Dylan’s appeal is based largely on the mystery of his unfixable identity, as Haynes himself posits, then there’s no need to “get inside” Dylan, even a fictional figment of him. It’s the kind of attempt belied by Dylan’s remark to a cowed newspaperman: “The truth is just a plain picture.”

Of course, that remark is countered by another Zimmerman adage: “We all have our own definitions of all those words.” And so we’re back at the beginning, back at that maddening desire and demand for the artist—or anyone, in fact—to explain what exactly he really means. And how, after all, can anyone claim to describe a “plain picture” of themselves or someone else when the truth remains forever elusive? Is Pennebaker’s film therefore just one more dead end (eat the document!) in our quixotic quest to “know” Dylan, especially in putting forward a manufactured “plainness”? I’d like to think not, if only for the reason that of all the Dylan films out there (and there seem to be exponentially more by the year) Dont Look Back remains the first and only essential one for keeping Dylan in its sights with an almost obsessive intensity and letting the man himself perform his version of the truth, no matter how conceited, charming, possessed, or banal—and precisely because it seems like, but is in actuality far from, the “plain picture” he resolutely refused to paint.