Movie 2.0

By Violet Lucca

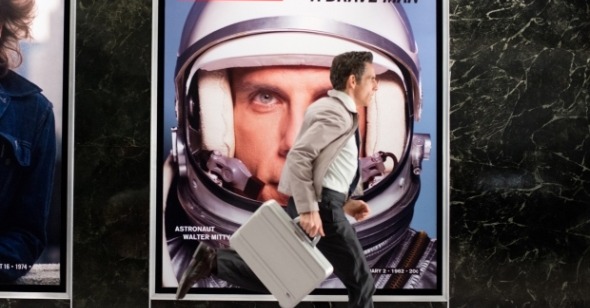

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

Dir. Ben Stiller, U.S., Twentieth Century Fox

A tangible side effect of the digital age, next to the possibility of everyone turning into fat, unsympathetic, selfie-snapping consumer blobs, is the decline of a unionized workforce. White-collar workers make up 60% of the workforce yet have less clearly defined rights than their blue-collar counterparts. Email and smartphones more often than not mean an employee is on-call 24/7, eroding the hard-fought 40-hour workweek. But the Internet and all its notification-giving accouterments are only slightly more recent a phenomenon in the history of humanity than labor rights, and it’s clear that we, in the most global sense, are living through the moment where one either wins out over the other or some (legitimate) balance is found.

This reality has nothing yet everything to do with Ben Stiller’s incarnation of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which uses the slow dismantling of Life magazine as the framework for a storyline that is little more than a hollow succession of product placements. “I used to have a mohawk, a backpack, and an idea of who I wanted to be,” moans Mitty (Ben Stiller), who oversees the developing and archiving of photographs for the venerable publication. However, as the above quote evinces, Walter is so broadly written and so blandly inoffensive that it’s hard to conjure any empathy for him, a generic, truism-embodying hero for the image meme age. (Why—or if—he loves photography goes unsaid; he does do a few sick skateboard tricks though.) The only thing aside from the title preserved from James Thurber’s 1939 short story, also filmed in 1947 by Norman Z. McLeod, are Walter’s escapes into flights of fancy, the alleged universality of which the film’s creators were obviously counting on to fill in what their test-audience-safe characterization could not.

But even these fantasy sequences are little more than unimaginative CGI wish fulfillment: after being insulted, Walter makes a cool zinger instead of saying nothing at all; Walter has superpowers and pushes the prickish man in charge of firing everyone (Adam Scott) through a plate-glass window; Walter becomes a sexy Latin lover to impress Cheryl (Kristen Wiig), his equally unremarkable and unfunny love interest. The Ally McBeal approach to interior life on display here is in stark contrast to the anarchy of McLeod’s version, which unapologetically broke the fourth wall in order to showcase Danny Kaye’s talents. (A particularly absurd but delightful example of this is when, after having already imaged himself as a public school–educated RAF captain, Kaye delivers an extended Borscht Belt–ready routine of an Eastern bloc music professor directly to the camera.)

Given that the rights to this remake have been kicked around Hollywood for over a decade, the generalness of the escapism and players is understandable—anyone could’ve stepped into Mitty’s shoes, and it just happened to be Stiller, who also directs. (This choice perhaps unintentionally echoes the realities of post-crash, Internet 2.0 staffing: the person who fulfills multiple positions at a time.) While screenwriter Steve Conrad repeats the arc of the Kaye film (nebbish who gets swept up into a plot that’s more improbable than his daydreams), Stiller lacks the subtlety of gesture to convey the sorrow and troubles of an emotionally dead man in a dying industry—his “sad” and “worried” faces are so obvious we might as well be reading those words on screen. This performance is a far cry from the overly tanned narcissists and nihilistic weirdoes he’s developed for screens small (The Ben Stiller Show, Heat Vision and Jack) and large (The Cable Guy, Zoolander).

Walter is as inauthentic as Stiller is, and his motivations are extremely muddled. Having discovered that the negative of a final cover image for the magazine sent by Hemingway-lite/daredevil photojournalist Sean O’Connell (Sean Penn) has mysteriously disappeared, he spends an untold fortune on last-minute trips to Greenland, Iceland, Yemen, and Afghanistan in the hopes of tracking O’Connell down. (He also upgrades his mother to a $4000-a-month retirement home suite in one of the film’s many “Save the Cat” moments.) Why anyone who’s soon to be unemployed would take such steps is half-explained by Walter’s need to fill out the “been there, done that” box on his eHarmony profile and impress Cheryl. Aside from his coworker Hernando (the underutilized Adrian Martinez), Walter seems to have no friends, a void that is filled by calls from an eHarmony phone rep (Patton Oswalt), who repeatedly contacts him at key moments on Walter’s cell (which magically has service in Greenland and the Himalayas). His interactions with Walter are reflective of the social-media relationships people have with large corporations; kindly yet creepy, he constantly tracks Walter’s movements while always encouraging him to relate his life experiences to the product or service provided. His coup de grâce is saving Walter from detainment at LAX after assaulting a rotund TSA agent, a scene that is animated in the style of an airport x-ray scanner, a bid at silent comedy that only manages to be oddly racist. (Aunt Jemima and her bulbous bosom are alive and well, and work at a shitty security job.) When the two men finally meet, they celebrate over a Cinnabon, repeatedly saying the word “Cinnabon” as they Cinnabond.

Walter Mitty may be a film that features a character who’s basically a retargeting ad that speaks in sponsored tweets, but it’s beautiful in a way that neither mainstream nor independent films aspire to anymore. As much as the setting and Walter’s profession might suggest, the film is a eulogy for the medium’s passing—whatever you’re supposed to feel for Walter (and probably don’t), you might be made to feel about 35mm. The range of colors cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh captures, and how they are used, are impressive in a way that’s jarring in comparison with the relative mediocrity of the rest of the film. Rather than the standard “INT – BORING WORKPLACE” grey/beige color palette with buzzing fluorescent overhead lighting, the fictionalized Life offices glow with blues and teals, contrasting with dark chocolaty brown wood and white walls. It almost makes sense that someone wouldn’t want a life outside an office this gorgeous. In a choice that drives home Life’s role in photojournalism and American visual culture, a handful of the magazine’s iconic covers (Marilyn Monroe, Vietnam, the moon landing) are incorporated into the mise-en-scène through large-format reproductions in the office’s hallways. When Walter returns to the now-empty offices towards the end of the film, there’s a palpable sense of loss. At other moments, such attempts at visual expression drift into melodramatic Baz Luhrmann territory: one half of Life’s motto is imposed onto a passing ship, the second half in the clouds of the following shot (a tactic frequently used by Pinterest quote-image meme-makers); a lonely Walter looks out the window of a plane and sees a flock of birds in the shape of Cheryl’s face.

The tension between these clumsy, pop-operatic moments, scored to semi-recent indie-pop songs, and the rest of the film’s casual shot-reverse shots is never fully resolved. One cannot help but feel something when listening to music, but that one part of Arcade Fire’s “Rebellion (Lies)” where they sing “ohh” for, like, two minutes cannot possibly chart the progression from inertia to perspicacity—even if that’s the intended evolution of the character. Walter’s journey is so broadly drawn that it’s never clear what he’s moving away from or toward. The most universally satisfying Hollywood films are usually predicated on a dialectical relationship—a rom-com with a neatnik and a slob; a musical where the poor kid gets the rich girl. But Walter Mitty is too clumsy and afraid to offend to properly take that journey, not unlike its titular character. Walter is reduced to the image meme that people “like” because they want to show support for something or feel good about themselves. This is art for the age where web 2.0 companies are your best friends—even an attempt at beautiful or clean, Bauhaus-style populist design seems insincere. A photograph of a sunset is no longer a sunset, but a desktop background or something over which to lay an inspirational quote. These signifiers become commodities, not unlike our time and efforts.