The Underneath:

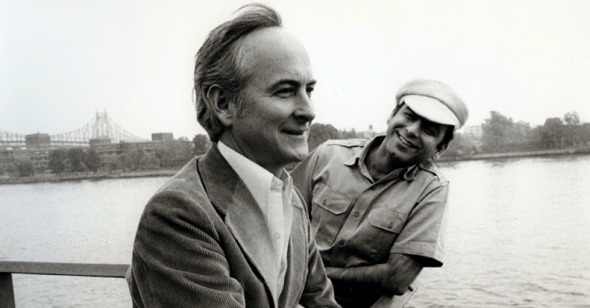

An Interview with James Ivory

By Frank Falisi

The dust jacket that adorns Solid Ivory—filmmaker James Ivory’s 2021 collection of fragmentary memoirs—contains an odd detail. “At times, he touches on his love affairs,” so the copy goes, “looking back coolly and with unexpected frankness.” And surely, the book does find the filmmaker striking a glorious balance of commemorative and dishy, recalling nascent sexual encounters with the same clear prose as he does memories of food his mother prepared in his youth or shooting conditions on any number of the films he directed.

That Ivory’s frankness is “unexpected” though, reiterates the too-common, misaligned critique that the films Ivory made, mostly in partnership with Ismail Merchant, were merely stuffy costume dramas and period pieces, rather than elegantly sketched moving portraits of men stunted by social and political mores and women courageous enough to crave cinematic life. The films are often extraordinarily sensitive contraptions motored by desire.

Watching and rewatching Ivory’s work in 2024 reveals that a certain frankness around love and life was always a part of that operation, even as obviousness was avoided at all costs. In Merchant Ivory (2024), a new documentary film by Stephen Soucy, Ivory supposes that a degree of that frankness is due to the films being composed from an outside view, whether it was as a Californian seeing India or England or as a gay man telling stories of the heroic women of E. M. Forster’s Howards End. Most remarkable in a run of more than 40 films Merchant Ivory produced from 1963 to 2009 is Maurice (1987), an adaptation of Forster’s novel about homosexual love, first closeted and finally acted on. That Merchant and Ivory released the film—as much an image book of body-to-body connection as it is a cry of despair—into an America in the throes of the AIDS epidemic is a definitive note on the filmmakers’ direct and serious approach.

Speaking with Ivory over video chat about the recent documentary and an August Quad Cinema series of his and Merchant’s work, I thought of Forster’s own postlude, the “Terminal Note” at the end of Maurice. “A happy ending was imperative! I shouldn’t have bothered to write otherwise,” the Englishman wrote. “I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows.” Forster’s inclination towards a fiction that preserves life is no imperative to flat optimism. Written between 1913 and 1914, Maurice wasn't published until 1971, a year after the death of its author, who was out to his close friends but not the public or his readers. The “Terminal Note” writes a happy ending in place of living one. It's a spectral echo taken up by Andrew Haigh in All of Us Strangers and the late Terence Davies in, among other works, Benediction. These are films haunted by the possibilities of using art or God in place of life itself, rather than as crucial graces we stay alive for.

At 96 and given to speaking about his sexuality frankly and unromantically, Ivory has outlived Forster by five years. That he is still writing, remembering, and rendering is better than a happy ending: it's life.

***

RS: You mention, in the new documentary, that whenever Jefferson in Paris (1995) plays on a big screen, you try to see it. Is that true of all your films?

JI: Yeah, well, yes. I mean, I like to see one of my films on a great big screen, naturally. I mean, if I can do it. And so, if I find out there's a screening of something I haven't seen in a while, I go to it. Yeah, I love it.

RS: Will you get a chance to see The Remains of the Day next week, at the Paris? They’re showing it on 70mm, I think.

JI: The original super wide screen, whatever the format was. I don't remember any other. They don't make those films anymore. They don't make those prints anymore.

RS: Do you find yourself looking to different places in the frame? Maybe the work of a director is suggesting where the audience should look but also leave space for them to look elsewhere. Do you look elsewhere when you see them again?

JI: Sure. Sometimes there's a certain amount of disappointment. Or thinking I should have done something in that corner: I didn't.

RS: Can you be generous to yourself?

JI: I am, I have to be, but I'm quite self-critical really. I was watching our fourth Indian feature the other day, Bombay Talkie (1970), and I was astonished at how much walking with sad faces there was, and people saying…I don't know what. I can't remember anymore. And I thought, I should have sped that up a bit. So, things like that.

RS: How much figuring on-the-fly was necessary in those early films in India?

JI: Well, it’s a lot to figure out. But principally, we had to figure out where we were going to get the money. And we—I mean, Ismail—always managed to. And there was almost no film where we weren’t really strapped, when it came right down to it.

RS: Did that hustle start sort of right away, with The Householder (1963)?

JI: Yeah, Ismail wanted to do it. Supposedly, it was given to him by a writer named Isobel Lennart in Hollywood. And she said, “Look, if you want to make a good movie, make Ruth Jhabvala’s The Householder, her fourth novel, make this into a film because nobody out here would ever, ever touch it.” And supposedly that was what started him going. I never found that book though. Well, the train was really on the track with The Householder because amazingly, we sold it to Columbia Pictures for worldwide distribution. We made two versions, one in Hindi and one in English.

RS: Did it get any easier to get the money together after The Householder?

JI: Not always. The way it went was—in our independent way—if you made a film and it was a big success, then the studios wanted to hire you to do a film for them. Okay. And so you made that film with the studios. You've got a lot of money to do it with. And then that film doesn’t do so well. So, the studios get anxious about making another film with you. And you had to get across a period where they were anxious until you got back to another period of good graces by another hit of some sort. And then they wanted to give you money again. That's what it was like all along, starting with The Guru (1969).

RS: There’s a moment in the documentary when someone calls Ismail a con man. Of course they do it with a smile, but does “con” feel like the right word, making these movies this way, constantly turning the process over?

JI: Of course, and I say it every day. I mean, any independent film producer is a con man. You can't help it. You have to con everybody. And eventually you get the money, but you never make a penny from the film.

RS: Were there other times where a particular adaptation simply came about because there was a book that seemed right, like The Householder? Taken as a whole, the films sometimes feelbiographical via periods of interest, rather than personal history.

JI: Well, that happened several times. I happened to find a book that Ruth was reading, which was Quartet by Jean Rhys. She just left it somewhere, and I picked it up and started reading it. I’ve got to make this into a movie. I'd always wanted to make a movie about the twenties in Paris. And that's what that is.

RS: Do you know right away when a book is not a movie? Is there something in the language that doesn't work for images?

JI: Well, sometimes I think something is a film and I had to fight with Ruth a little bit. For instance, about Quartet. I wanted to make Quartet immediately into a film and she said,“Oh no, Jim, it's so low-spirited.” Well, it's not low-spirited. It's got one of the best nightclub scenes in any of our movies. There aren’t many movies with Armelia McQueen singing. Gosh, it's fantastic. Anyway, there were other occasions. Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. I knew the Bridge novels by Evan Connell. I had read both of them and I told Ruth I thought Mrs. Bridge would make a wonderful film. And she didn't think it was a good idea at all.

RS: Ruth had some issues with Maurice as a novel, is that right?

JI: Yeah, she thought it was an inferior one of Forster’s novels, and not up to the others.

RS: On the one hand, it makes sense that you’d want to adapt a novel that inherently works, and in a way that suits moving images. But Maurice feels like a case where certain imperfections in the text can almost be solved in the adaptation.

JI: And it's Ruth who solved it. She solved it, she added that bit about Lord Risley. And then for Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, it helped because we put the two books together, Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge. Joanne was going to be Mrs. Bridge, and we didn't have a Mr. Bridge. I mean, we weren't even thinking Mr. Bridge. And then Paul said, “Well, why don't you do the two books and I'll be Mr. Bridge.” Well, once that happened, there we were. We immediately got the money.

RS: What was it like to welcome Joanne and Paul, who already had their own long-standing collaborative language, into that sort of orbit?

JI: It was less difficult than I thought it would be. We thought it was going to be some scary, big star kind of world that we're gonna have to tiptoe around in, but it wasn't like that. They were remarkably fine. Everything was fine except the back of Paul's neck. He wanted his hair to be a bit long. Well in 1930, men didn't have long hair on the back of the neck. We had to practically hold him down to shave it.

RS: Those are such rigid characters, sometimes comically so. But like a few of your films, it sometimes feels like desire is the thing that’s moving around, under the surface. Does that seem right to you?

JI: The desire?

RS: Yeah, sort of finding it in relationships that maybe have to struggle to express it. Chasing it.

JI: Well, there’s this desire to get the film made, for God's sake!

RS: Can you will a film into existing, through that desire?

JI: I mean, it was hard, hard work, working in India because there were so many governmental restrictions, things you couldn't do. And also, sometimes you couldn't get film stock, or if you couldn't get some piece of equipment you were dying to have. Access that would have been normal in Europe or the United States, sometimes they didn't have it in India, things like that. You had to make do. On The Guru, our lead [Utpal Dutt]—I can't remember why—was put in jail. It was only for a few days. I think he spoke out about something, and they jailed him. He wrote for an extreme, far left newspaper in Calcutta, and was quoted and so forth, and was considered to be worse than a communist. And he also had to go to Mrs. Gandhi to get him out. So, he was in jail for ten days and then he came back to the set.

RS: Does this kind of retrospective mode feel natural to you right now? Between the new documentary, the Quad Cinema series, the recent memoir, does it feel good to be looking back?

JI: Sure. Yeah, it’s fine. It’s good. I like it, particularly when, with so many people, they seem awed by my very presence in the room. This has never happened before, even on my set.

RS: What are you working on right now?

JI: Well, I have an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. This is called Ink and Ivory. And it's a show of Indian drawings. And by that, I mean, these are the drawings by the artists who did the Indian miniatures, the initial drawings for many of them. And it’s a show of those drawings, some of which I own, some of which The Met owns. And so that’s on until next May.

RS: And are you doing any writing?

JI: Well, I've just written something that's going to come out in some arts magazine in London, and I don’t know what the name of it is because it’s the first issue. And I do have this little book [holds up a journal] of all my thoughts about ever going to Mexico, all the trips I made to Mexico. So, it’s a little book I’m going to go through and type it up, and hopefully somebody will want it. Getting another thing made.