Lessons in Darkness:

An Interview with Cinematographer Frederick Elmes

By Nicolas Rapold

It’s astonishing that the first feature Frederick Elmes shot as director of photography is Eraserhead—a film in which darkness and light feel like visceral substances, inseparable from and indispensable to David Lynch’s vision of a loner’s private hell. The four decades of films he’s shot since then include many such defining, headlong works of independent moviemaking: with Lynch, Blue Velvet and Wild at Heart, but also River’s Edge, Night on Earth, The Ice Storm, and Synecdoche, New York. Another crucial part of Elmes’s career was his formative work with John Cassavetes, serving as camera operator on The Killing of a Chinese Bookie at the same time (quite literally) as he was DP’ing Eraserhead. While Jack Nance’s Henry was trudging wide-eyed through an alternate-world Philadelphia abyss, Elmes was also exploring a different underworld with Cassavetes and Ben Gazzara on the Sunset Strip.

I sat down with Elmes to talk about working with Lynch and Cassavetes on the occasion of a Metrograph “Filmcraft” series of films he shot. (And next month, the Criterion Collection releases a 4K UHD Blu-ray of Blue Velvet.) As I shared stills from his films in a cozy office at NYU Tisch, where Elmes had been teaching, the soft-spoken cinematographer revisited these years with a kind of wonder. “The education I got in filmmaking with two very, very independent and unique filmmakers at the same moment was just beautiful,” he said.

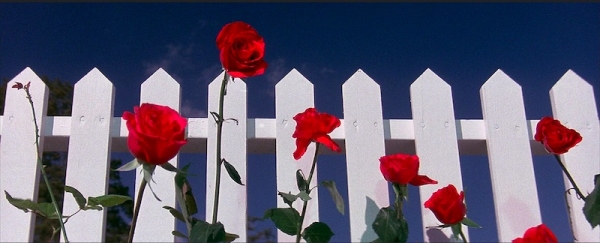

Reverse Shot: Let’s talk about the opening sequence of Blue Velvet, which establishes this light-filled, postcard-perfect view of suburban life.

Frederick Elmes: It’s funny because it sets this idyllic tone that’s hardly in the rest of the film. Because we dive in pretty quickly to visit the insects and it’s kind of a gruesome journey. But before that, we get this impression of life on this sunny residential street that couldn’t be safer or more innocent. That is really Jeffrey’s character [Kyle MacLachlan] in the very beginning. And as soon as he gets a little bit of knowledge that he’s not supposed to have, he just can’t help but fall over the edge and keep investigating. So that’s what Blue Velvet is about: seeing that underside, and his quest for that information he doesn’t have. But for me, it was always foreshadowed by these first few images.

RS: When did you shoot the opening scenes?

FE: We ended up shooting them pretty much the last day of photography, but it was all in the script. David wrote every one of these shots down—the tulips, the roses against the white picket fence, the fire truck with the smiling firefighter. And somehow by shooting this late in the day, this fire truck driving by goes from sunlight into shadow and then back into sunlight and shadow. And because the man is staring at us and waving in very slow-motion, it has this eerie, eerie quality. It is a mood-setting thing. It’s like they’re too perfect. The fence is too white, and the flowers were just picked. They’re just swaying in the breeze in sort of an unnatural slow-motion way. There’s no shadows anywhere. It’s a perfectly blue sky. And [the looks of] those tulips and white picket fences were inspired, for me, by a still photographer named Paul Outerbridge, Jr. He used a very early color printing process that made colors a little bigger than life, a little more unreal feeling, and he does have a picture of a white fence and a rose and a blue sky with a little cloud in it that I particularly like.

RS: What goes into getting that red of the fire truck?

FE: Mmm-hmm—it’s important. We tried a couple of different color film stocks, and we did tests with different wall colors, different colors of blue velvet [for later shots], different colors of red flowers, to see how they would photograph. And we found a stock and a process that we really liked that really made the colors come to life.

RS: Is the slow-motion wave done afterwards or in camera?

FE: It’s done in the camera. I think that’s the best way to do it because in camera you’re actually capturing those 36 or 48 frames a second. You have all that information. You’re not generating it later by doing an optical. You have it built in, it’s smoother, and I think in a way eerier, to set a mood.

RS: The flipside of that too-perfect opening mirage is Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), raging at Jeffrey and Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini).

FE: Oh, my God... Here we get to see just how bad Frank Booth is. This two-shot comes at the end of this scary joy ride Frank and his buddies take Dorothy and Kyle MacLachlan’s character on. It’s supposed to be Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. And in David Lynch’s mind, the way he wanted to photograph the film was to make it feel like I had been strapped to the outside of the car, moving at 75 miles an hour down a dark road, and I was just looking in the window, trying to capture these little bits of information about this joy ride. It was all going to be kind of one shot. “And you don’t mind being attached to the outside of a racing car?” [Lynch asked.] Luckily, the producer stepped in and said, “No, we’re not going to do that, and you can’t actually move the car because we don’t have enough time in the schedule. So, we want you to shoot this all standing still.” To fake it, basically—create the illusion of motion and terror in Kyle’s mind at least.

I came up with a solution when we were shooting late one afternoon. We built a tent that was black on the inside. I decided that the best way was to only shoot the inside of the car with really big close-ups, and have Kyle in the backseat hunkered down, pressed down into the seat. So, he can’t really see everything. You can only see little bits of the different characters. And you can’t see anything out the window behind him, mostly because there was nothing out there. You know, we were standing still. So, the only thing that you can see outside is a little bit of moisture on the window, lit by a passing headlight. We faked all those headlights; we jiggled the car. I was hand-holding the camera, and we just made it up as we went along and made it terrifyingly claustrophobic inside the car—the close-ups, the jiggling, the sound of the car, this driving music, and a bunch of cutaways of the yellow line down the middle of the road or the bridge they’re going over or streetlights whizzing by. We built the whole impression of going fast out of this series of abstractions.

RS: What was it like being close to Dennis Hopper when he’s letting loose like that?

FE: It’s scary. Dennis was a very charismatic actor who was completely captivating, and to be in a closed car with him playing that character was a scary proposition because he really filled the car. You felt him in a very visceral way when he turned to the camera and put that gas mask on. I still don’t know exactly what it is he’s breathing or doing there, but it puts him in a different zone. He becomes this other person.

RS: Every detail in Eraserhead is so carefully designed. Here also begins David Lynch’s lifelong love of sconces...

FE: Sconces! We had some good ones, we did. I really learned a lot about lighting wall sconces in this movie. There’s something about paying that much attention to the detail of the way the light comes out of a sconce, the way it works on a wall. When you put that much light on the wall and let other parts of the frame fall into shadow, there’s a real contrast you set up. You set up an area where you see things and an area where you don’t see things, and it’s those shadows that David and I became completely fascinated with. We always used to say, we’ll light the actor this way and we’ll light part of the bed that way—but then we’ll let what’s next to the bed fall into shadow. And we found that we just couldn’t make the shadow dark enough. It was so beautiful to have that mystery in the frame next to something that was lit. We fell in love with that feeling. I think that’s part of what helps set the tone in Eraserhead: that contrast between what you can know and what you don’t know, the light and the dark.

RS: How do you get it dark enough?

FE: Each bit of light on the wall is a very specific light—it only does that job. And it doesn’t spread anywhere else. And then you just take the light away from everywhere else. You have to fight to take the light away. So, there’s a light from over the elevator that lights the carpet—but that’s all it lights. It doesn’t spill anywhere else. And you don’t even see the rest of the chair. That sense of the graphic quality of the light and the dark really intrigued me completely.

RS: How do you work against or rethink the conventional light of the real world when you’re imagining a new world in a certain time period?

FE: Oh, that’s a good subject. The world where Henry lives in Eraserhead is very particular, and it’s really not tied to today. It’s not tied to any era. I don’t think it was groundbreaking, it just didn’t want to be current day. This was shot in the early ’70s. It’s pretty old-feeling stuff, it’s kind of comfortable, yet it’s presented in a way that’s maybe uncomfortable by virtue of the light and the mood of it. It was really its own planet. And Henry lives in an industrial world. We shot [exteriors] in Los Angeles, in Beverly Hills, the land of sunshine, but we could never, ever shoot on a sunny day. We had to wait for cloudy days to come.

RS: How did you come to work with John Cassavetes on The Killing of a Chinese Bookie?

FE: When I moved to Los Angeles and went to the AFI, I met David Lynch and got to work on Eraserhead. But simultaneously I had an opportunity to meet John Cassavetes, because there was another cinematographer at the AFI who started to work on A Woman Under the Influence. I came on the crew for a couple of minutes, and then their relationship dissolved, so I walked away from it. But I stayed friends with John because they were editing right there at the AFI. And I knew a lot of the editing crew and so on. At one point, John came up to me and said, “I’ve got this other film, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, with Ben Gazzara, and I want to know if you’d like to work on it.”

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie was this ragtag crew of friends, of John Cassavetes and me and some of my friends who I brought on to help. It’s just unimaginable because I’d been such a complete fan of John’s work. I knew his films well before A Woman Under the Influence, and I loved watching him work with Gena [Rowlands] on that film. But what I realized was John wanted me to come on because I was a film student and didn’t know how to do things. What he really liked was being surrounded by people who were discovering how to make movies. Clearly he was the director, and it was his story and he knew these characters well, but he wanted to make the film with people who were not part of a Hollywood film crew. He didn’t want the gloss of a Hollywood story. He wanted the underside of Sunset Boulevard, the seedy clubs and the gambling scene and the would-be gangsters. It was a world that I really wanted to explore with him. Fascinating, a little bit dangerous, and, you know, kind of cool.

And if you watch a John Cassavetes film, it’s completely the opposite of a David Lynch film. I mean, David working on Eraserhead was a very precise experience, and we shot very meticulously with a very small crew, and only what we needed. John Cassavetes—who was also making a film the only way he knew how—was much looser and more open to things that the actors would bring to the table. John was much more interested in feeling the performance in a scene, and if something he had written wasn’t working as the actor said it, he would throw the script out and he would rehearse something with the actors and improvise and then write it down and then shoot it again in the way that felt right to him. John needed it to feel alive and somewhat improvised at the moment of photography.

RS: And that must mean you’re having to redo setups a lot?

FE: Right, so you are, and sometimes you miss. As the camera operator on Chinese Bookie, sometimes I would pan with the actor, and I would say, “Look at that—we got it, he’s in frame for the whole way of the pan he runs across the room. I think that’s about as good as it gets.” And John would say, “I think I need one more.” Ben Gazzara would run across the room again, and I would pan with him, and John would walk past the camera and elbow me. The camera would go kabump in the middle of the take! I would say, “Oh, you know, there’s a bump in it.” And he would say, “Yeah, it’s great.” So there was something about the energy of that spontaneity that John Cassavetes wanted to see in the photography somehow.

RS: This is quite a pair of filmmakers to be starting out with.

FE: And they happened simultaneously. We had to say to David, “I need to take a little break. I have a paying job for a while. Can you give me a month off here?” And David was very tolerant of us because I would take the crew and go to work on something else and then come back and we’d continue Eraserhead.

RS: The paying job was The Killing of a Chinese Bookie?

FE: This was the paying job. Even though David paid us what he could, John Cassavetes could pay a little more. So, I had to do it, being a starving student.

Elmes and I talked about more films, but just as we were about wrap up, he wanted to return to Blue Velvet, for one particular shot...pictured at the top of this article.

FE: That’s a nice moment, for me, because Isabella performed several songs onstage. And this is Angelo Badalamenti in the background playing the solo piano for her. She was quite marvelous and a little bit nervous about standing up in front of an audience, because there were people out there listening to the performance, and she’s not a trained singer. So, making her feel comfortable was part of it, even though the camera starts back 20 feet away from her and does this very slow dolly move in, meticulously, to this close-up at the end, because that’s the shot that David and I had designed. So, to capture that—yet put her in a place where she felt she could perform convincingly as that character—was for me magical. And this combination of the production design—which was Patty Norris, who was a costume designer—with the red curtains, and this blue, blue light, because David had decided that she really had to be in blue light some of the time. That’s the name of this particular song, as it happens.

What’s happening off camera is that Kyle MacLachlan and Laura Dern’s characters are sitting back at a table watching the performance, and at a certain point, since he’s seen it before, he knows that’s their cue to leave because he’s going to sneak into the apartment that night, right? So, he’s got the whole thing timed out, but the scene is really about Laura Dern: Dern watching Kyle’s character watching Isabella. And it starts here, in the club, a thread that’s really integral to David Lynch’s story.

To capture that moment, we did the take a couple of times. And in just one take, when the music ends, she turns into a profile, and the light goes out at exactly the right moment where you have just her dark silhouette against red curtain. It really only happened once that we got it to perfectly fall like that, and it was by accident—we didn’t design it. But that’s the one that’s in the movie. So, for me, that’s what makes these dramatic moments work. And it was the perfect cut to Kyle in the car.

RS: Chance was a collaborator.

FE: Chance is always part of it. And for me, that was really brought to light by working with John Cassavetes, because he wanted it. He created situations where that could happen, where something could unfold and the difference between this take and that take was often markedly different because he pushed things in a different direction and something new happened that we hadn’t quite expected. But that’s the fun of moviemaking, the magic—some of which you plan, some of which you don’t.