Wish You Were Here

An Interview with Olivier Assayas

By Eric Hynes

Narrative cinema, as well as literature, operates on multiple levels. There’s text and subtext, a present, past, or future tense of the material simultaneous to the present tense of the viewing, images both materially recorded and spectrally projected. In that light, ghost stories are particularly native to the form, as the narrative echoes the alchemical process of creation and presentation. With Personal Shopper, Olivier Assayas does more than rely on this idea—he compounds and interrogates it, crafting a work that operates on several planes of existence simultaneously.

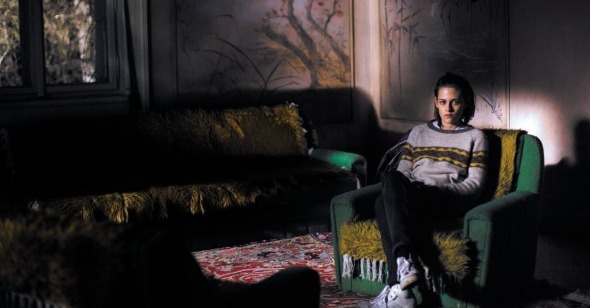

Maureen, played by Kristen Stewart, is both a spiritual medium and a personal shopper to a famous fashion model. It’s worth noting that as mediums go, she’s a deeply skeptical one, and she finds personal shopping frustrating and demoralizing. In both modes, she’s dealing with absence, conjuring or trying to locate presence and meaning from the reluctantly departed and the willfully scarce. To all of this, Assayas layers two historical iterations of ghosting that serve as provocative analogues: the contemporary experience of technologically dependent, physically disembodied communication via text messaging and Skype calling, and the late 19th century/early 20th century wave of spiritualists who sought to connect with the afterlife. The way in which these two eras are linked—while transiting through the city, Maureen watches YouTube clips about Victor Hugo-led séances on her iPhone—is pure Assayas in its deceptive banality, its nonjudgmental deployment, and its in-the-moment layering.

Olivier Assayas spoke to Reverse Shot at the 2016 Toronto Film Festival, the day after the film’s North American premiere.

Reverse Shot: I was really fascinated by your invoking fin de siècle spiritualism in this very contemporary story. It’s an analogy I certainly didn’t anticipate, but it’s stuck with me. How did you come upon it?

Olivier Assayas: I wanted to make a film about the tension between our inner world and the outer world. Especially within the context of living in a society that’s increasingly materialistic and rejects anything involving spirituality, or the imagination. I think that as much as we’re obsessed with materialism, the essential part of ourselves happens in our thoughts, in the weirdness of our inner world. So it was exciting to connect it to a moment in time when artists and people in general genuinely believed in the existence of some kind of other world. It was a short period of time, beginning in the mid 19th century and lasting until the early 20th century. And there’s a logic to it—it was a period of incredible invention and discovery. All of a sudden you could do things that were unthinkable throughout the history of mankind—flying, using the phone, X-rays, radio transmission, you name it. So this whole notion of things happening in an invisible world became a total reality. I used two striking examples. One is the art of Hilma af Klint, an incredible artist who was genuinely convinced that her hand was guided by an invisible presence—by ghosts or whatever you call it. It’s not a metaphor, it’s not a communication tool—it’s her life. She was a medium. And she was one of the inventors of modern art. Even the other painters, like Malevich and Mondrian, were theosophists. So the invention of abstraction has deep roots inside this notion of communicating with the invisible. And then there’s Victor Hugo—he was the opposite of a madman, he was the most rational writer. Yet when you read his transcripts, he was turning tables. They’re beautiful modern poetry, the fabric of a lot of what he wrote afterwards, and it’s based on the faith in the factual reality of another world. So I was interested in making a film that had some kind of dialogue with this moment when the presence of the unknown was a part of our lives.

RS: By invoking that other moment, and these notions of the beyond, you’re imbuing these things that are very familiar to me—texting, Skyping, the loneliness and disconnection of technological communication—with a bit of heft, some depth, and history. An easier move would be to diminish these modern experiences.

OA: Our interaction with screens, our interaction with texts—it’s always communicating with something or someone that’s not there, that is virtual. And that virtuality is what’s been left, it’s the rubble of our conviction in another world.

RS: You made me realize that texting is somehow more intimate than Skyping.

OA: I do think so. In fact I’m convinced. Because I believe in words. Yes, because I’m a writer, but also I think that with the intensity of the text messages, and their density, every single word we write is super charged. Not when you’re saying, “Sorry, I’m late.” But when you’re careful with words, the texts have an intensity that’s similar to that of poetry. And I think it’s more powerful than conversation. Because in conversation there are things you don’t dare say. There’s a certain brutality to text messaging.

RS: In the film you explore the power play of having to wait for the next text, or of making the other person wait by not responding right away. As with the spiritualists, you’re talking to entities that aren’t physically present. And cinematically you’re exploring the benefits and challenges of being in two places at once.

OA: That’s what I was interested in—representing with film this notion of two things happening simultaneously, and how whatever is happening in the text is more important than what’s happening as Maureen is traveling.

RS: Even though she’s passing through interesting places, she’s barely paying attention to the world she physically inhabits.

OA: You don’t see. You’re lost in your inner world. Which is sometimes scary. It happens to me once in a while. You get involved in practicalities, and start texting and sending messages. You’re at the airport, you’re traveling, you’re here and there, and when the conversation is over—well the conversation is never over, it goes on and on—then you feel like you’re emerging, that you’ve been underwater and going to the surface.

RS: You’ve been present and not present at the same time. Which is interesting in terms of Kristen Stewart because she has this amazingly strong presence. A quality that’s hard to always see or define, but it’s definitely there.

OA: She has an incredible physicality. She’s like a dancer. She has a way of moving onscreen that’s mesmerizing.

RS: But you’re working with it in a different way. We’re drawn to that presence, and yet for long stretches she’s less present than she might otherwise be. She’s seated, she’s staring at her little screen, she’s silent. How do you modulate and direct that?

OA: I hardly direct it. She directs it. For instance, if we’re discussing the scenes with the text messages—she has her phone [takes the reporter’s phone], and I’m here [points to the reporter] with this little screen, and I don’t see her phone. So in terms of pacing, I don’t know what’s going on. Or I don’t completely know what’s going on. I know that we are doing those three or four lines, but I have to try to understand just by watching her, by which line she’s actually reading when she’s reacting. And when you do five, six, seven takes, you’re completely lost, you have no idea what you have. I ended up only discovering what Kristen was doing in those scenes when I was in the editing room.

RS: I’ve seen you mention on numerous occasions that you felt you were being challenged and changed by Kristen, and as you just said, that she was directing you. Specifically how was she changing you? Because even casting her in these two movies would seem to imply that you were already moving in a different direction.

OA: It’s that she’s on her own. I can only compare it to what I was doing with Asia Argento. Boarding Gate is also a movie where the star is on her own for much of the movie. When you write dialogue scenes for two or three characters, you intercut. The rhythm of the scene, the structure of the scene is something you’ve designed. The actors have space to reinvent and give it their own pace, but still it’s pretty structured in that there are a few lines here, then they stand up and go over there. It’s a whole choreography that I’ve designed and controlled. Then in the editing room I can structure it the way I’d imagined it in the first place. But here it’s tracking shots, and often shots where she’s on her own. So she decides on the pacing. I have very little space to edit. The rhythm of the scene is something she’s inventing on the spot.

RS: And the camera follows along according to that?

OA: You’re adapting to her. If you’re doing a shot of her walking, when she hears something, stops, starts again, hears another thing, turns around—she has to feel those things. They have to build up inside of her. And you can’t command it. I was increasingly dependent on how those things happen inside of her, and she gives them a fluency. They don’t look fake. I can’t tell Kristen for those scenes to do it faster. It makes no sense. Because she’s doing it as fast as she can. She needs to sense things. Feel the space. What’s the use of having her do something that she feels is fake?

RS: I don’t want to be presumptuous, but I’m struck by your exploring belief in this. I’m assuming that you’re a skeptic to some degree, or have been in your life. And yet there are phenomena in the film, moments of the supernatural that can’t be rationally explained. I’m moved by it, but I don’t know how to reconcile it.

OA: I don’t believe. I would love to, but I don’t. But I believe in faith. I have faith in faith, if that makes sense. And I think that faith can be an important part of our lives. I genuinely think that there’s more to it than the material world, even if I’m not sure how to verbalize in what exactly I believe. But I do believe in something. And I think we all do. And so my belief in faith is very much a part of this film. With the ending, her vision of her brother comes when she’s lost faith. When he appears behind her in the kitchen it’s the moment when she doesn’t believe anymore. That it happens and she’s not aware of it is frustrating and sad, because he was there and she couldn’t see it. Then I needed an epilogue in which she rebuilds her faith, when all of a sudden it opens up.

RS: But it goes beyond appreciating the idea of faith, I think, in that you’re making visible the invisible, for the audience. And that’s a delicate thing to pull off.

OA: Oh, yes. It’s like a high wire thing. What I end up filming that’s the closest to the invisible is the glasses[falling]. The rest are visions.

RS: Meaning you can attribute the visions to her point of view?

OA: Yes, but even those visions need to have some kind of materiality. I had to show something at some point just to give reality to whatever was happening inside of her. And for that my inspiration was really spiritualist photography. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, mediums would be taking photos. Which is really fascinating. They’re very naïve and spooky also. I like the idea that those pictures were taken by people who had genuine belief in what they were showing. So I thought if I use the texture of those images to express whatever Maureen is seeing, it makes sense, it can work.

RS: But the sceneat her sister-in-law’s house is different in that she’s not looking in that direction, meaning we witness a supernatural manifestation. You make it literal.

OA: Yeah, because they actually break. They do fly, and they do break [laughs.]

RS: I can’t help but associate it with the finale of Stalker, and the shot of the glass sliding off the table on its own.

OA: Yes it’s true, I’d forgotten.

RS: Which is somehow immensely moving. The inanimate object as proof of life.

OA: Tarkovsky is the greatest. In terms of making movies that deal with the invisible, that touch those strange, dangerous areas, no one is better than him. In The Mirror there’s that the moment when he’s sitting with his mother and looking at the wheat field, and you have the voice of the poem written by his father who had abandoned them, and all of a sudden the wind shakes the wheat field. I’m not even sure how he did it—perhaps with a helicopter—but it just breaks my heart every single time. I just start sobbing every time I see it. It’s genius.

RS: He’s using cinema to explore the miraculous, and in that moment perhaps affirming the existence of another world, or the beyond, without necessarily himself believing in that other world. It seems cinema is the realm where that’s permissible.

OA: Because cinema does film the invisible. You don’t have to believe in the invisible—it’s factual that film images capture something more than what you’re shooting. You think you’re shooting something, but in reality you’re shooting something else, something more complex that is inhabited by more than whatever you think you’re actually doing. And it’s something you realize when you’re editing, and when you’re discussing it with people who have watched the film. Film, for some reason I’m not sure I’d be able to completely verbalize, is intimately connected to perception, and our perception involves seeing things and feeling things. You see things that are there and you sense things that are not tangible. But they are not less real. The emotions that someone has, whatever someone expresses, it’s not entirely something that’s said. And cinema records it. Movie shots are always in the end more complex in terms of what inhabits them than whatever you initially imagined. And that’s the limit or the stupidity of a lot of filmmaking within the industry. They always think that everything can be controlled. They are obsessed with control. Control is like the opposite of whatever moviemaking is about. You should not want to control. It’s the highest goal in filmmaking to lose control. That’s why it drives me nuts when I have to discuss screenplays and, you know, “this is too long, and this is too much of that.” What the fuck? When the movie is on the screen it will be something else. They think they can control it. But they can’t control shit. Nothing. No one controls anything.

RS: Furthermore they’re killing it.

OA: They end up killing whatever can be exciting, beautiful, and strange about movies. That’s why you have such a sense of movies that have been devitalized.

RS: But conversely, you can’t really force excitement, beauty, or strangeness.

OA: You totally can’t force it. And eventually it does not happen [laughs.]

RS: But you have to try to set the terms, create the conditions.

OA: You need to try as hard as you can. It’s the only way cinema brings you back something that’s worthwhile.