Empty Rooms

The Films of Kalil Haddad

By Alexander Mooney

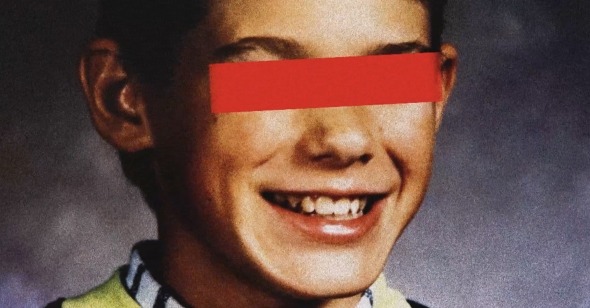

“Farm boy Steve needed to escape, so he sold the only asset he had: his youth.” The line is all too familiar, suspended between tragedy and fantasy. Steve, Michael, Adam, Sean, Jordan; in the2022 short film The Taking of Jordan (All American Boy), these teenagers blend and bleed together, united by their imagined fates—seduced, exploited, abandoned, murdered, martyred. Kalil Haddad’s soul-stirring cine-collage draws from a bottomless well of deathless imagery, suturing together snapshots of amateur porn shoots, casting couches, bedrooms, deathbeds, censored yearbook portraits, blood-smeared crime scenes, and hogtied children. It evokes the perils of sexual discovery for impressionable queer youths with no safety net, and the incalculable costs they pay for humanity’s unchecked desires.

The rest of Haddad’s filmography, showcased with the seven-part program “He Never Dies” at New York’s Spectacle theater and Los Angeles Film Forum through the month of July, is similarly committed to exploring the coexistent harshness and beauty of gay life. The Toronto-based experimental filmmaker has spent the past several years implicitly challenging what it means to “represent” queerness; his work makes no compromises or apologies in confronting the complex lineage of violence, abuse, and exploitation that lingers beneath the surface of physical passion for so many young people stepping out of the closet and into the wild. He often finds these undercurrents lurking inexplicit images disseminated by queer pop culture, and in the imagined plights of the sex workers who’ve been immortalized by them. His works traverse a wide range of subjects—from real-life familial traumas and fictive yearnings to abstracted archives of lovers, dreamers, and victims—but a mainstay in his filmography is the pall of an uncaring, and often predatory, world which queer adolescents are frequently forced to navigate alone. The notion that gay lifestyles are fundamentally lonely and perilous is, of course, absurd and antiquated, but this acutely provocative filmmaker meets such stereotypes head-on, exposing their roots, testing their limits, and probing their lasting impact on queer narratives past and present.

In the program's first entry, The Beautiful Room Is Empty (2020), Haddad conducts interviews with his aunt Marie, a retired high school principal. She reflects on her childhood, unravelling the knotted dichotomy between her lesbian identity and the demands of a feminine role in a strict Arab household. Haddad’s camera patiently surveys their family home, now vacant, waiting for the next owners. While her younger brother (Kalil’s father) mows the lawn one last time, Marie describes how her unwavering devotion to her family and their Palestinian roots coexisted with the fear of rejection by her parents. She eventually divulges that she was sexually abused by her older brother for several years. These parallel secrets would shape the subsequent decades of Marie’s life; her brother threatened constantly to out her to their parents (and once, to the board of education), while Marie was bound by a code of silence, wishing in spite of her own suffering to spare her family further pain.

Marie’s recollections, seemingly recorded over Zoom during COVID, are laden with skips, cracks, and glitches, imparting a sense of artifice that only pulls the audience in deeper—a contradictory effect that’s now crucial to the filmmaker’s detached, enthralling style. Our position within these tactile sites of anguish is equally unstable; static shots of window frames, screen doors, and various sunlit interiors are digitally manipulated to zoom in and out, drowning focal points in pixelation. This technique is deployed regularly by Haddad (a film editor by trade), whose tendency to inject kineticism into still frames and motionless camera setups befits his penchant for cobbling together narratives from forgotten fragments and disparate scraps.

These subtle aberrations pave the way toward his documentary’s most outwardly experimental gesture; a photo of eight-year-old Marie prior to the assaults is juxtaposed with another taken years later, her face blotted out by a white void at the center of the frame. As a steady strobe pulses cathode-blue light, we zoom into this blank face and zoom back out of what’s revealed to be a television set. The scene calls to mind two different images from Twin Peaks, another devastating treatise on the evil that can blossom in the margins of a loving household. Unlike David Lynch’s doom-laden feedback loop, The Beautiful Room Is Empty finds solace on the other side of the void; we finally see Marie as she is today, on a video call with her nephew, grateful for what she learned from these ordeals and for having achieved love and fulfillment on her own terms.

_(1440p)_4_.jpeg)

The central figures in the rest of Haddad’s films are not so lucky. The Beautiful Room Is Empty is something of an outlier for Haddad, whose works so rarely conform to the contours of real life, and even more rarely conclude in such a sanguine register. Three gloomy stories of abject longing follow it in the program: Vampires Drink Blood… I Drink Sorrow (2021), My Secret Boyfriend Died in a Mass Shooting (2025), and His Smell (2023). The first of these follows a soul-sick figure (played by Haddad) as he prowls the streets of Toronto by night, remembering his lost love (Josiah Dyck). This goth-tinged reverie walks a fine line between hyperbolic angst and palpable yearning—Haddad shoots his object of desire in sultry, swooning closeups, while his nocturnal wanderer is captured in isolating wides and long-lensed tracks as he broods through dark alleyways.

The film’s grainy, step-printed imagery would become a signature for the director going forward. His Smell—which observes a similarly long-faced yearner (Sebastian Neme) seeking fulfillment by proxy—finds Haddad using these lo-fi techniques for a softer, but no less sorrowful, tone. The young man eyes his roommate (a partial silhouette at the edge of the frame), who tells him it's time to move out and move on. In the roommate’s absence, Sebastian makes a phone call, smokes some weed, and remembers his first love, a high school friend who died in an accident. Infrared shots of the boys frolicking in the snow in their underwear are contrasted by present-day Sebastian’s impulse to fish a pair of boxers out of his roommate’s hamper and inhale the scent. “You could’ve never been him, all you ever shared was his smell,” he says, but he touches himself to the aroma anyway.

My Secret Boyfriend (his latest, which made its world premiere at L.A. Film Forum) is a doomed love story told through distorted stills from an erotic photoshoot. It begins with title cards—his preferred mode of exposition—typeset over crimson storm clouds, which set the scene of a teenager plagued by visions of the future. On a rainy morning, with parents out of town, his boyfriend comes to visit. These images—make-outs and handjobs on the couch, fellatio in the shower, tender intercourse on the bedsheets—are reframed, remixed, and recontextualized by Haddad’s virtual camera, with a dreamy score morphing from sexy slo-mo beats to an ethereal, piano-laced soundscape as an impending tragedy draws closer.

Screams and gunshots play atop an image of the two embracing at arms-length, strobing from black-and-white to deep red. “That night, as he lay in dreams between my arms, I decided I would never speak to him again,” hovers over the screen. Blood seeps through blurred, shaky footage of wounded bodies and first responders, ending on a freeze-frame of a man at the camera operator’s feet. This abstract portrayal of the preemptive measures the narrator takes to shield himself from a portended loss raises questions about the inveterate fear that courses through the elations of queer romance. We are inundated with narratives of hateful violence, taught to believe that we and our loved ones might be destined for such a fate; the narrator’s father also had visions, but they dissipated when he settled down with a wife.

These three stories of romance torn asunder by forces beyond their characters’ comprehensions seem quaint in comparison to the program’s final stretch. The Boy Was Found Unharmed (2024) tells the story of abuse survivor Jody Plauché in miniature. His father Gary famously gunned down his eleven-year-old son’s molester—the boy’s karate instructor, Jeff Doucet—in full view of a television camera. Footage of this event is soundtracked by audio recordings of interviews with Jody as an adult. This act of vengeance—reportedly executed without a trace of emotion—only drew more attention to Jody, whose father was widely regarded as a vigilante hero and managed to avoid jail time. The film ends with a series of screenshots from Plauché’s cooking channel, displaying comment after comment extolling his father. A message saying “comments are turned off” is followed by a prolonged shot of Doucet bleeding from his head wound.

“He Never Dies” concludes with The Taking of Jordan and its spiritual successor, Victim of Circumstance (2024). Though the former is likely Haddad’s most essential work (and currently his best-known), Victim of Circumstance is the culmination of his longstanding techniques and fixations. The ambitious project sets its sights on the failures of the gay liberation movement to protect its most vulnerable during the sexual revolution that accompanied it, wielding various artifacts of pornography’s so-called Golden Age for maximal distress.

Recounted through voiceover by Matthew Levak, the story follows two boys, Scott and Brandon, who meet in an orphanage. Scott describes nightly gang-rapes by the other boys, from which Brandon eventually rescues him. The two find a nudie mag in the woods and fantasize about the life they could have—“If you have the face, the body, and the desire, we have the management expertise and international connections to get you to the top,” reads one of the pages. Brandon ages out of the orphanage, and by the time Scott has escaped and caught up to him in Sunny California, his lover has vanished without a trace. Scott imagines the worst. We see excerpts from an article titled “The Traumas of Gay Teens,” in which the writer pleads for the gay community to better shelter and mentor its communal children.

A harrowing four-minute montage follows; pounding strobes accompany a wailing, discordant soundtrack as hardcore footage is crosscut with shots of a real-life autopsy. The sequence is overwhelming, assaultive, sickening—I have not watched it through once without crying. After another silent interlude of onscreen text (this one scrolling through dozens of personal ads), Victim of Circumstance ends with footage of a poolside orgy. The voiceover tells us that Scotty, like the twenty or so men in the movie, is competing for the prize of a brand new motorcycle. An upbeat song scores this fun in the sun, and in the final moments, an aural reference to The Wizard of Oz returns us to an uneasy, trancelike state.

The film has a bleak outlook on queer life, to say the least. Haddad’s work is destined to be taken to task for playing into negative tropes associated with the gay experience: sexual violence, pedophilia, the specter of AIDS, and a totalizing shroud of loneliness. But these confrontational films—through their many shattered taboos and brazen, brutal shock tactics—are composed with an unmistakable compassion, and a wisdom and perspicacity that seem beyond Haddad’s 27 years. These raw and unguarded works—brimming with passion and vibrating with anger—amount to a full-throated resistance to the systems of power, belief, and capital that have deluded and violated queer people ever since they were allowed to exist in the open. His attention to the politics and history of queer image-making gives me hope for its future.