This Must Be the Place

by Kelli Weston

Column 1: Bunny Lake Is Missing (London, West End Lane)

On the subject of her revolutionary designs, the Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi famously characterized her discipline as “an adventure in which people are called to intimately participate as actors.” She is describing how each of us invariably collaborates daily with the structures we pass through. At the risk of taking her too literally, whenever cinema restages our real world “performances”—the way we behave (or don't) at dinner, at church—the people on the screen often cannot afford to be so indifferent to their environs. In horror, the house may terrorize or, in certain extravagant cases, possess its dwellers; in melodrama, her walls may be a prison so burdensome that the characters psychically carry them everywhere. Outside the odd experiment (e.g., Ben Whishaw as Bob Dylan as Arthur Rimbaud in the spectral, white space vignettes of Todd Haynes’s 2007 film I'm Not There), where we are in a film almost always has something to say about the nature of belonging, and so, almost always says something about identity: how it’s made, broken, or otherwise disrupted. In cinema, we cannot escape the genealogical project folded into setting. Characters are helplessly in dialogue with the lineage of “place” on and off screen. The home is so perilous in melodrama and horror alike because the family is usually the first site of violence (psychological or otherwise); intuitively, at least, we all already believe in haunted houses.

Our imaginations forge our borders as surely as our borders forge us. Virginia Woolf demanded a room of her own, but Charlotte Brontë's lady in the attic might've had something altogether different to say about that. For ultimately we are the ones who affix meaning to place: a house becomes a school; a hospital becomes a theater; a cinema becomes a church; so on and so on. Children know this intimately: nudge a chair here, upturn a table there, and a room shapeshifts under a blinking eye. We—not transgressive, culture-defining architects like Bo Bardi, but “actors"—create place, socially and personally. In that way, the places we occupy are always transforming, even when nothing moves.

As someone woefully haunted by the houses where I’ve lived and all the many rooms I’ve only ever visited vicariously—from a plush red chair in a darkened room or half buried beneath tangled blankets in bed—I have always been a little distracted by passing environmental details. This ongoing column will explore those many, returning distractions, exacerbated by my late discovery of Reyner Banham, the architectural critic: for him—and he is not alone—architecture is storytelling; it is anthropological. The study of place is at once historical and prophetic. What follows is my own unschooled mimicry.

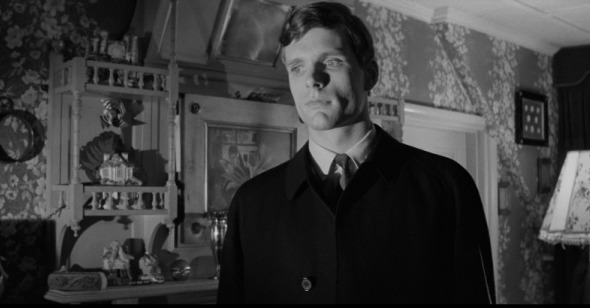

When I first watched Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), I had recently left London, where I lived for the better part of a decade. So I found myself surveying the background of Otto Preminger's strange melodrama even more than usual, scouring for all the places that had once been home to me, as they existed fifty years before I'd ever set foot there. The title does all the heavy lifting: Ann Lake (Carol Lynley)—single, unwed mother to “Bunny” (née Felicia) Lake—returns to the preschool where she has left her daughter only to discover the child has mysteriously disappeared. In fact, no one seems to recall seeing the little girl at all. There is no record that she was ever enrolled. Nor can Ann, newly arrived in London, where she joins her journalist brother Steven (Keir Dullea), produce any photographic evidence of Bunny's existence because most of their possessions—including, crucially, photo albums—have not yet reached England. By the time the police reach the Lakes’ new flat, none of the child's belongings—mug, bib, bathrobe, teddy bear, etc.—remain there, leaving only two conclusions: either they (and the child) were snatched (but who would go to such lengths?) or they were never there to begin with. Much of the drama hinges upon Ann’s teetering credibility. As far as the audience knows, for we have yet to see Bunny ourselves, the child may indeed be an invention. Resolving the mystery thus falls to the reserved and often inscrutable Superintendent Newhouse (Laurence Olivier).

Preminger famously despised the ending of the novel of the same name by Merriam Modell (writing under the pseudonym Evelyn Piper), which reveals a spinster schoolteacher, assisted by Bunny’s grandmother, as the kidnapper. “I found the villain, the old woman who stole the child, was uninteresting,” said the director. “It’s a completely arbitrary solution, and it doesn't make much sense.” Preminger could, by then, speak with some authority on the matter: His best noirs Laura (1944) and Fallen Angel (1945) were already behind him. In pursuit of his own—as it turns out, darker—vision, he cycled through predictable luminaries (Ira Levin, Dalton Trumbo) before finally landing on then-married screenwriters John and Penelope Mortimer. The Mortimers set about translating the material for the screen: Blanche Lake in the novel becomes Ann, and she is given a protective, peculiar older brother.

But the most significant change was in location. While Modell’s novel was set was set among the chic, aging brownstones of New York’s Upper East Side, Preminger wisely transported the tale to London, where he shot entirely on location. Soho, Trafalgar Square, and Maida Vale all make distinguished appearances. The scene of the crime, called The Little People’s Garden School in the film, is still standing (under another name) in Netherhall Gardens, near Finchley Road, Hampstead. Steven lives in the fictional “Frogmore End”—postcode NW3—in a house that is really Cannon Hall, the childhood home of novelist Daphne du Maurier. For years, I lived a stone’s throw away in the somewhat less fashionable end of NW that is Kilburn, driven there by lifelong literary romances (of which du Maurier is counted): Zadie Smith grew up ten minutes away from the cramped flat where I spent much of my twenties; and I was in walking distance of Keats House, where the poet John Keats resided in the years before his fateful voyage to Rome. Whenever I made the breathless trek to Finchley Road, I took the long way, through quaint West End Lane, studded with elegant, red brick affairs and pristine cafés dense with well-dressed families. That area of London is fairly affluent and, informally speaking, home to many foreign transplants (Americans seem especially drawn to the western hubs, e.g., Notting Hill and Holland Park).

It seems important that for all Preminger’s revisions, refined by the Mortimers, they preserved the central characters’ nationhood. Indeed, pesky cultural distinctions exacerbate the case. Ann and Steven are given—often fairly—to emotional excess, doomed to clash with the perfunctory graces of their new compatriots, whose reserve and lack of urgency unnerves them. In that way, the film is not just about the mystery its title proposes, but the physical (and possible psychic) displacement of an already “unconventional” family.

Naturally then, Bunny Lake seems especially preoccupied with location and the tension its characters bring. There is, notably, Ann’s flat, where she is beleaguered by her lecherous landlord Horatio Wilson, played with mustache-twirling relish by the playwright Noël Coward (who shares only one scene with best friend and frequent collaborator Olivier). When the moving men, one of them Black, carry furniture into Ann’s apartment, they are struck by a wall embellished with large African masks, which Wilson parades around like trophies. In another scene, Newhouse takes the distraught Ann to a Maida Vale pub (also still standing) where the English rock band, The Zombies, play on television. He leans toward her with a collegial smile. “Ever been to a pub before? Well, here it is. The heart of merry old England.” He is right, but not quite precise. If the pub is the heart, then Ann’s flat, garishly decked in its out-of-place masks is an image closer to the truth of England.

The school, obviously, offers the richest implications. We find the retired cofounder of the school, Ada Ford (Martita Hunt), tucked away in an attic room where she listens to recorded interviews of “children’s fantasies” for a book she is apparently writing. She adds, with no small eeriness, “I have all their little nightmares on my tape machine!” But Miss Ford turns out to be the most perceptive of all. When Steven threatens to call the police, she replies matter-of-factly, “It’s exactly what I should do myself were I the child’s father.” And when Steven explains that he's Ann's brother, she responds with a smirk and a chuckle barely concealed in her throat: “Curiouser and curiouser.”

This brings us to the “First Day” room, the last place Ann apparently saw Bunny. The first time we see Ann, she is leaving and shutting the door of this very room. But we do not see inside until the investigation begins. Everything we know about what passed there arises from her increasingly frenzied testimony. The “First Day” room, appropriately, looks like a nursery. It contains a crib, where Ann claims a toddler had been placed, when she left her daughter. There is also a swing, a rocking horse, and the walls are graced with sketched portraits of various items (nouns)—table, cat, chair, bed—and their corresponding names in bold block letters. Characters move in and out of this room, all of them adults, broadly oblivious to its embellishments. It is the seriousness of the happenings there that intensifies the childishness of the space. Here, Newhouse conducts an informal interrogation of Steven, who tells him about his childhood with Ann. Their father died in the second World War; their mother was highly religious and not much concerned with her children. We begin to get—pointedly, in this youthful space—a portrait of neglected childhood. Steven explains that he became Ann’s guardian and protector. It is rather clever storytelling, whether you find the chilling ending of the film satisfying or not, for it heralds the conclusion both narratively and aesthetically. In this sequence, Newhouse leans on the rocking horse and Steven idly dangles on the swing, designed such that he appears to Newhouse as if in the center of a triangle. Steven had confessed (though he later denies it) to Ada that as a girl his sister had had an imaginary friend, also called Bunny. Play is at the core of this set piece and more crucial than we yet know to this film.

Here are some curious thoughts that occur to me as Newhouse pursues the truth in the nursery: It is no accident, I think, that Britain's relationship to its former and even adjacent colonies slips so often into the film. Horatio tells Ann that one of his masks—“marvelous for fertility”—comes from Ghana; when we first encounter Steven, he is preparing for potential protests over the arrival of a Congolese diplomat. And however valid their distress, the Lakes are archetypically American—intrusive, overbearing, shrill, temperamental—leaving Newhouse an undeniably paternal (and patronizing) presence. Indeed, the key to the mystery, strangely enough, lies in the ship that conveyed the Lakes to London. Of course, the Lakes are white; and Preminger, on and off screen, possessed only a passing grasp of race and empire (despite wading repeatedly into its pyre) that keeps these themes undeveloped. But it is curious how much the nursery sequence brings to mind so many other unnamed thefts, abductions, and disrupted or else scattered lineages. For all this talk of children, we rarely see them; instead we have their trappings (dolls, teddy bears) and the places you might keep them (nursery, crib). In this room, peopled with adults behaving strangely, this glaring absence is central, a “missing” that begs to be filled. The very definition of a haunting.

The feeling that greeted me when I finally found what I was looking for in Bunny Lake—streets that were both familiar and yet not—was something similar. Everything looked like a memory, although I had never been to the Piccadilly Circus or Soho of 1964. What followed was something like grief for a place I could never really return to, except in my mind.