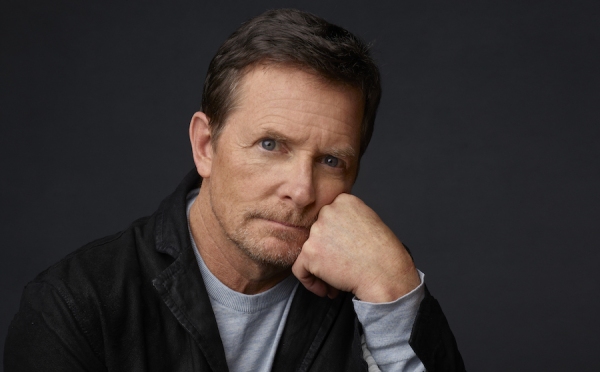

Our Guy:

Celebrating Michael J. Fox

By Greg Cwik

There are all kinds of actors: those who disappear, as they say, and in their place summon a living, breathing, bleeding, quivering human character. There are the enigmatic monsters, the Max Schrecks and the Lon Chaneys, and of course there are the students of Lee Strasberg or Stella Adler: the Brandos and Pacinos and De Niros and Day-Lewises, who allegedly stay in character during shoots, the kind of actors who tend to win awards. We have character actors, too, like Dennis Farina and Margo Martindale, always welcome, usually cast in supporting roles to erect a stable structure for the leads to play around in, actors you recognize who may not look or sound so different from role to role but possess an uncanny, compelling quality that is unmistakably their own. And then there are those rare actors who are just plain likable, the kind you trust to keep you entertained, actors imbued with an inherent magnetism despite their eccentricities, like Eddie Murphy or Tom Hanks.

Back in the day, when television and film weren't interchangeable, the most agreeable, affable actors often ended up on network sitcoms. As the episodes accumulate and you spend more time with them, they offer the comfort of familiarity, like the company of an old friend, reliable and loving, whom you see on a regular schedule. Michael J. Fox is such an actor, beloved out of the gate with his breakout role in the early eighties as the young Reaganite Alex P. Keaton on Family Ties, an epochal sitcom that probably wouldn't exist today, as it invites us to love a young man with reactionary politics. After this, he did something unusual: he established himself as a movie star, pervading popular culture for the next three decades. Fox is perhaps the sitcom performer who most successfully translated his innocent ebullience and endearing kineticism from television to film. (The fear of television typecasting is very real: while filming a particularly stressful scene in Brian De Palma's ferocious Casualties of War, Sean Penn went up to Fox and hissed in his ear, "Television actor.")

Fox remains underappreciated, even if his name is universally known. Though he has portrayed villains, complicating his genial presence with calm, collected menace on such TV shows as Designated Survivor and The Good Wife, it's as a charismatic nice guy, the reluctant semi-hero, for which Fox is still and probably always will be remembered. Yet he's played a variety of characters with myriad complications and problems. Good luck finding anyone who actively dislikes Michael J. Fox, but we have taken him for granted, maybe because the culture continues to favor actorly histrionics. You can't learn his kind of charm at the Actors Studio. As Marty McFly in Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future trilogy (1985–90), which began when Family Ties was at the apogee of its popularity, Fox captures the clumsy passion of teenage dreams and the difficulties of love (not to mention the threat of incest), playing matchmaker for his own parents, always finding the right note for the unutterable anxieties— including the fact that his dad is a loser but he loves him anyway.

Marty McFly feels like an intentional riposte to Alex P. Keaton; the kid who wanted to drag America back to the less enlightened ’50s has now been literally hurled back there, in very ’80s attire, finding himself aghast at the era's regressive uptightness and lack of rock 'n' roll. In the opening scene—slamming a guitar chord and blasting out Doc Brown's speaker, frantically skateboarding to school so late you wonder why he bothers—Marty is the kind of guy you root for before you know anything about him. Maybe it’s the puffer vest. And look at Teen Wolf, at the furry felicity with which his hound-boy plays air guitar to The Beach Boys atop a wobbly old van cruising along the tree-lined Nebraska streets. Imagine Lon Chaney, senior or junior, this boyishly effervescent.

David Thomson wrote in his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, “Today, McFly seems as quaint as Andy Hardy, but truly he is the 1980s version of that archetype, and one of the last examples of the principle that decent energy can make you a star.” Compare him to today’s blockbuster stars, with their bulging biceps and abs you could chip a tooth on. Fox doesn't do accents or vacillate between weights or slather prosthetics on his face. You always know it’s him. In Back to the Future, when Marty and Doc Brown go undercover at high school, he slicks back his oiled hair and takes big baby drags of a cigarette, the sickly gray shreds of smoke slipping out of his mouth. Fox doesn't look right like this; his charade is unconvincing. That's what makes it endearing. He's a kid playing dress-up as a kid from another era. (In Family Ties, he's also playing a kid masquerading as a man, a Republican pastime.)

In the wake of his enormous success, he was seen as a perpetual boy. He played teenagers until he was 26. So he started to take tougher roles, pretty much nailing all of them, even in movies best left forgotten. In the comedy The Secret of My Success (1987), he plays a smart, hungry young man who discovers the cruelty of corporate New York. It was his first “adult” role, and it cleared $100 million. The next year, he waded into serious territory with James Bridges’s 1988 adaptation of Jay McInerney’s cocaine-coated Bright Lights, Big City (the novel is notably written in an intense second person), shot by Gordon Willis with a beauty that both belies and captures the insalubrious behavior of young, dumb boys who will sip or snort or screw anything to feel alive. He partnered up with a pre-alt-right James Woods in the silly buddy cop comedy The Hard Way (1991) as a popular actor who goes undercover with a real cop in desperate pursuit of respectability. The film, a hoot, made almost $66 million, even if it has dissipated from public consciousness. In the same year's Doc Hollywood, he's surprisingly snarky and selfish at first, getting stranded in a small nothing of a town when his car craps out—finally he becomes the Fox we all know and love when he grows to adore the town and its everyday people. And as all millennials fondly remember, Fox, a prolific voice actor, lent his vibrant, affable cadences to a dog trying to traverse the dangerous wilderness in Homeward Bound (1993), and to the title character in the Stuart Little films.

It's tough to talk about Fox’s craft because it’s unshowy, always empathetic, and unencumbered by the obvious virtuosity of actors we tend to reward with prizes. Fox is perfectly cast “outside his comfort zone,” in Brian De Palma’s profoundly unpleasant Casualties of War (1989), a savage story about atrocities committed by American soldiers in Vietnam. When the film came out, Fox was criticized for being out of his depth. Thomson opined, "Admiration for Fox cannot cover up the fact that he was a narrow or limited actor who rarely rose to more demanding material." But there’s an honest, terror-stricken look on Fox’s boyish face, his skin flush from the red, hot blood in his veins as the war roils around him and he sees men—boys, really—giving in to their wickedest inclinations. Fox plays off Sean Penn's vulgar histrionics with trembling terror, his innocence shattered by the cruelty of reality. His wide, shell-shocked eyes shine with sweat and hot tears; he looks as though his heart is throbbing so intensely it may rupture out of his chest. In the end, confession is all that can ameliorate his pain—it’s all been a nightmare.

Fox’s versatility is underappreciated. He shines regardless of story and situation—sober severity for De Palma, and then silly spectacle in Peter Jackson's The Frighteners (1996). The film's computer effects have aged worse than the practical effects of Jackson’s Dead Alive or Brain Dead, but it thrums with wacky ardor. Fox brings an everyman normality to the role of a con man who can communicate with the dead and who talks three of his spectral buddies into “haunting” houses he then expunges for a modest fee. Here, Fox gets to play another regular guy in a surreal scenario who does (minor) things of a morally dubious nature but you like him anyway. That same year, Fox tested his likability as a smooth-talking, dog-hating news reporter who gets cucked by Pierce Brosnan's severed head in Tim Burton's Mars Attacks! (perhaps the only time you root against him), and, most happily, he returned to network television with the sitcom Spin City, a funnier proto-West Wing.

Fox was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 1991 while shooting Doc Hollywood. His initial symptoms included uncontrollable twitching in his finger. He was given a few years before he would be unable to perform, but he gave us another two decades of work. After going public about his diagnosis, Fox took a hiatus from film (though he did voiceover work), although he made notable TV appearances, as on the sitcom Scrubs, playing a severely OCD-afflicted and brilliant doctor who conquers his germaphobiaby using a toilet on the roof. He has become a tireless advocate for Parkinson's research and has tried unwaveringly to make the world a slightly better place. Though he appeared in the documentaries Drew: The Man Behind the Poster and Back in Time, he retired in 2021.

Fox has dedicated the last 20 years to researching Parkinson’s and sharing inspirational stories and advice. Speaking to Davis Guggenheim in the new documentary STILL: A Michael J. Fox Movie, Fox says, “Parkinson’s didn't just kick me out of the house—it burned the fucking house down.” But while the disease has limited the activities, even the quotidian ones, that he can do, it hasn’t sapped his spirit. He may struggle with a progressive disorder, but he refuses to give up control of his life. He rejects the easy allure of self-pity. STILL comprises an earnest, unadulterated interview with Fox and clips of his film and television performances of the ’90s, which bring attention to how careful compositions and props hid the tremors that would send his limbs into uncontrollable spasms.

Not everyone believed in Fox at the beginning. “I don’t think we’re talking about somebody who’s going to be on a lunchbox,” Brandon Tartikoff, the infamously powerful NBC president, once said of Fox before Family Ties erupted. Fox has graced many lunch boxes since. And shirts, backpacks, posters, blankets… In his book No Time Like the Future, Fox sums up his life outlook:

“When I visit the past now, it is for wisdom and experience, not for regret or shame. I don’t attempt to erase it, only to accept it. Whatever my physical circumstances are today, I will deal with them and remain present. If I fall, I will rise up. As for the future, I haven’t been there yet. I only know that I have one. Until I don’t. The last thing we run out of is the future. Really, it comes down to gratitude. I am grateful for all of it—every bad break, every wrong turn, and the unexpected losses—because they’re real. It puts into sharp relief the joy, the accomplishments, the overwhelming love of my family. I can be both a realist and an optimist. Lemonade, anyone?”

Photo by Mark Seliger