Behind the Screen

Conor Williams on It’s What Each Person Needs & Huahua’s Dazzling World and its Myriad Temptations

The films play together Saturday, March 18 at Museum of the Moving Image's 2023 First Look festival.

With so many contemporary sex workers live-streaming erotic shows to online audiences, or flirting with clients over video chats, the glass window of the peep show has transmogrified into that of the webcam or the cellphone screen. Sophy Romvari’s new short It’s What Each Person Needs centers on a young woman who straddles online sex work with another profession: elder care. Sitting at her computer in the neon valentine glow of a heart-shaped light, Becca Willow Moss mostly just talks to people. “Lonely people,” as she puts it to one client, “deserving companionship.” “It’s what each person needs,” states another client. What he needs is a blow job and someone to dominate. After her session with this man, who tells Becca he can’t spank her right now because he has to go pick up his kids, the film shows her speaking with an older woman over the computer. “You seem very genuine,” Becca tells her.

By shifting subtly between these two kinds of communication, Romvari’s film shows that elder care is not actually so dissimilar from online dating. (For a period of time last year, I tried working in elder care; I’d receive numerous emails from an organization with descriptions of clients and their interests. I never ended up finding the right old person for me.) Becca, meanwhile, is a much more patient and generous individual. She waits while her elderly clients figure out how to show their faces over Facetime. She sings Sondheim show tunes and classic Hebrew songs to them. “I lost everything, my husband, my house,” a woman named Yvonne despairs. Becca tries to encourage her. “You still have your memories!”

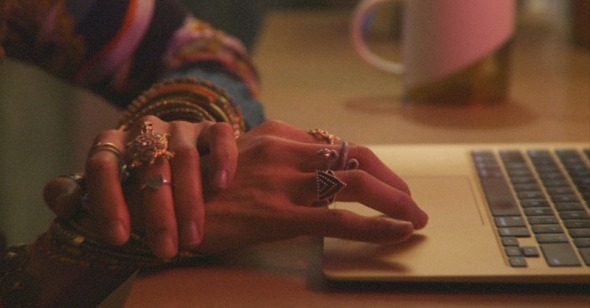

Cinematographer Maya Bankovic often contains Becca in tight close-ups. We watch her face and study it in much finer detail than her clients can through their cell phones or computers. Other times, the camera gets close to her jewelry—various rings, big gold hoop earrings, big bangles, bracelets. Romvari makes a reflexive swivel toward the end of her film, something she has done well throughout her filmography. Becca remarks that the piece they’re making feels sad. Romvari asks her, “What do you think this film is about?” Becca needs a moment to think about that, because as she puts it, she’s a “very curated person.” Again, the camera fixates on her jewelry. Her bright, alluring gems are now out of focus. As they gain their shape, Becca articulates her interpretation of the film she sits at the center of. It’s What Each Person Needs is a colorful, tender portrait of people in search of connection, and the performances people put on in order to make those connections.

Paired with Romvari’s short at MoMI’s First Look Festival, Daphne Xu’s feature-length documentary Huahua’s Dazzling World and its Myriad Temptations explores similar concepts within a different territory. Xu, like Romvari, is a Canadian documentarian, but her film takes place in China—specifically in Xiong’an New Area, a relatively new city formed in 2017 south of Beijing. Headlines tout the area as being “smart,” “green,” and “the city of the future.” “There are robots who can make cocktails,” a young woman says in the film.“ It’s super intelligent! It’ll be hard to find work in the future.” The “Dazzling World” that Xu’s subject Huahua resides in is that of the digital.

A gruff middle-aged woman, Huahua also makes a living performing for the camera, livestreaming, singing, dancing. She dances to a pop song that goes,

“Who says peasants don’t get tired? / The taste of a full day of suffering / Only peasants experience this / Wake up early and work until nightfall / Be exposed to the sun and the wind / Toil until the whole body is aged.”

Huahua grins. Her phone’s filters de-age and smooth her face. With this technology, she can eliminate signs of wear and age on her body. The app gives her a look that ostensibly connotes eternal youth, but it also looks eerie and sort of ghostly. Huahua’s phone is like an additional appendage. While dentists tinker around in her mouth, she holds her arm up to record it all on her phone. Huahua dances her heart out in front of a store, exclaiming to her followers the sales they can take advantage of. Decked out in black sunglasses, a hat, and a yellow sash, she throws her body around.

Huahua is illiterate, and we see her grandchildren are learning English. It’s clear she wants what’s best for her family. Speaking her mind on gender equality, she points out that women and men do the same jobs now. “The U.S. even has a female president,” she says. “Is that accurate? …No? There will definitely be one in the future.” Despite the hope Huahua speaks and sings about, Huahua’s Dazzling World is undeniably heartbreaking. She seems trapped behind the glass of her screens.

Facial filters can’t hide Huahua’s exhaustion or her deep cough, though they make for rather unsettling images. In one jittery, frankly terrifying sequence, Huahua and an older woman—maybe her mother—share the screen as a filter jumps restlessly between their features, frantically searching for what to modulate. The effect is like something out of Inland Empire. Toward the end of the film, Huahua monologues to different viewers because she can’t sleep. She talks about domestic abuse and complains about how tiring this constant livestreaming is. “It’s not good to keep watching. No matter how good my content is.”

Both It’s What Each Person Needs and Huahua’s Dazzling World and its Myriad Temptations make exceptional use of what’s left unseen. There’s Becca’s lustful men and sweet elder companions, and in Huahua’s Dazzling World, scenes are often punctuated with the off-screen sounds of ringing alarms, jingles, and the cacophony of cell phones. What’s off-screen seems to occupy the frame just as much as what we can see. Romvari and Xu are compassionate image-seekers, yet they also subtly interrogate the systems surrounding their subjects. In meeting these two women, generations and oceans apart, we can begin to see what effect the social aspect of our media has on our happiness, our relationships, and our livelihoods.