Have a Little Faith

Hazem Fahmy on Hail, Caesar!

This column features essays about films made in the twenty-first century that deal explicitly or implicitly with matters of American identity.

Since American capitalism can be understood as a national religion, where does one begin assessing the centrality of Hollywood evangelism in the 21st century? A mid-2010s movie set in a cartoonish version of the 1950s may seem an odd place to start, but it gets us there. In many ways, the Hollywood of today looks nothing like its classical counterpart as depicted in the Coen brothers’ 2016 comedy, Hail, Caesar! The contemporary American studio system is overwhelmingly global, its production radically less centralized, and it no longer primarily depends on theatrically released features for its revenue. At the same time, the Hollywood of the 2010s, and even more so of the 2020s, increasingly revives the past beyond its obsession with reboots and spin-offs. With the recent reversal of the Paramount Decrees, vertical integration is back with a vengeance, unceasing conglomeration means an unprecedented level of executive centralization, and the tirelessly successful model of franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, with its tightly controlled branding and multi-film talent contracts, is the closest thing we’ve seen to the classic studio system in decades.

The Coens’ Hail, Caesar! is perhaps not so much an underrated film as it is an under-examined one. As in their comedies like Raising Arizona (1987), The Big Lebowski (1998), and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), the brothers’ signature hijinks manipulate American mythology. More specifically, Hail, Caesar! skewers the theological role the film industry has played for audiences in the perpetuation of capitalism as a kind of faith-based culture. In returning to the filmic past, from a present of major industrial and cultural shifts, the movie sheds comic light on the cyclical nature of Hollywood. Everything looks different, but how much of it truly is? It’s tempting to think of the 1950s as a cinematically distant era. However, ours too is a time in which the studio system has been threatened by a new method of exhibition that has caused the movies to get bigger and bigger. Just as they eventually conquered television in the decade after its explosion, so too are the studios attempting to bend streaming to their will today.

Hail, Caesar! doesn’t reflect the contemporary state of American filmmaking and its relationship to the moment writ-large by being strictly “historical,” however. It is precisely the film’s exaggerated quality that makes it a fitting lens through which to understand the (often absurd) interconnected relationships between fantasy, faith, and capital. The Hollywood of Hail, Caesar! is one of half-truths. For starters, the true star of the film, Capitol Pictures, is at once a fictional institution, and yet is unmistakably MGM. The film-within-the-film, Hail, Caesar! A Tale of the Christ, is a hodgepodge of real MGM religious-historical epics, especially Quo Vadis (1951) and Ben-Hur (1959). One might be tempted to understand this pastiche as a kind of love letter to the era, but as Adam Nayman, author of The Coen Brothers: The Book Really Ties the Films Together, argues in his review in Reverse Shot, the film actually “functions simultaneously (and pretty much equally) as a critique and a celebration of the machinery of moviemaking.”

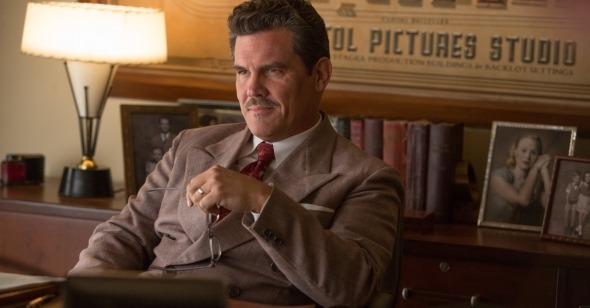

Though it’s an ensemble comedy, Hail, Caesar! primarily follows Josh Brolin’s fictionalized Eddie Mannix, a real-life MGM “fixer” who was responsible for ensuring the smooth flow of operations both on and off the lot. Eddie is stressed about the expensive Hail, Caesar! A Tale of the Christ, especially after the ditsy star of the picture, George Clooney’s Baird Whitlock, gets kidnapped by a group of communist screenwriters who believe they have been unfairly compensated by the studio. Hoping to make up for the royalties they say they deserve, they demand a ransom of $100,000 from Capitol Pictures in exchange for Baird’s safe return. While in their custody, Baird gets a crash course in communism and eventually returns to the studio disgruntled with its machinations. When he professes his newfound beliefs to Eddie, the fixer slaps and commands him to go do his job. The film ends as the production of Hail, Caesar! comes to a close.

In between Baird’s abduction and release, Eddie embarks on a kaleidoscopic journey across the studio and Los Angeles, encountering caricatures of prominent actors and filmmakers of the period as he attempts to put out other fires and get Baird back before word breaks out. From Scarlett Johansson’s impression of Esther Williams to Channing Tatum’s approximation of Gene Kelly, the cast embodies a vivid and satirical representation of the period, and the film reflects the feverish intensity of the Red Scare that defined the era. As a 2016 film about the 1950s studio system, Hail, Caesar! reminds us that Hollywood has always been a place of myth and self-congratulation, a dream factory that feigns progressiveness while serving national and hegemonic interests. The film is less interested in contemporary American identity itself than commenting on the executives and higher-ups who get to define and mold it. When Tilda Swinton’s frantic gossip columnist pesters Eddie to confirm the rumors about Baird’s kidnapping, he counters her demand that people know the truth by exclaiming, “People don’t want the facts!” They want a good story they can believe.

The Eddie of the movie is himself somewhere between fact and fiction. There was a real man by that name, but whereas the Coens’ version is a devoutly tormented Catholic family man, the real-life Mannix led a far less wholesome life. We may never know the true extent of his involvement in the often brutal control that studios such as MGM exercised over their employees, especially women, but it’s safe to say that Mannix’s tenure as a fixer intersected with some of the bleakest stories of the studio era, and he was even rumored to have been involved in the murder of actress Thelma Todd. Thanks to the work of historian David Stenn, we know that Mannix had a significant hand in one of the most mortifying and shameful episodes in MGM history, the cover-up of Patricia Douglas’s assault by an MGM employee.

The Coens’ Eddie is a man tormented by guilt, yet for all the wrong reasons. When we’re introduced to him, we learn that he goes to confession nearly every 24 hours, somberly telling the agitated priest that he has once again lied to his wife about his cigarette habit. He then drives to a house to retrieve a young starlet who was about to conduct an erotic photoshoot, slaps her repeatedly, and forces her to leave with him. As tame as that interaction is in relation to what the real Mannix actually did, there remains a distinct darkness to the Coens’ version, undermining the ostensibly romantic nostalgia of the overall story. This is, after all, a film about how filmmakers tell stories of themselves (and their country) through film. The Coens’ Mannix is a representation of the postwar studio system’s decay, as well as the violence its patriarchal leadership enacted behind the scenes. But his eclectic escapades throughout the studio are also a reification of Hollywood self-romanticism, an unsubtle reminder of the magnificent feats that machine was, and still is, capable of.

The tension between the nastiness of the historical Mannix and the relative gentility of the movie Mannix is but one meta element through which the film uses its semi-fictional setting to explore how the glamor of Hollywood conceals the machine whirring underneath. In their video essay on the film, “Hail, Caesar! McCarthyism, Metatextuality, and Why Movies Are Sacred,” Eric Sophia McAllister makes the point that there is little to no difference between the in-universe movie the characters are making and the real-world movie we are watching. It doesn’t even take that much time for viewers to note that Michael Gambon, the narrator of Hail, Caesar! A Tale of the Christ, is the very same narrator of the Coens’ Hail, Caesar! He brings an equally grandiose vocal register to both stories, eliminating any illusion that one is less cosmically significant than the other. A sense of the divine is intrinsic to the movies.

And yet that same sense is subverted and mocked. When Eddie watches dailies of Hail, Caesar!, the film is consistently interrupted by placeholder stills that read “DIVINE PRESENCE TO BE SHOT.” The divinity of the film is a work-in-progress––pending. Every time we seem to be on the verge of spiritual grandeur, the moment is deflated. At the end of the film, when the ransom is paid and Baird Whitlock is finally able to return to the set, he delivers the moving final speech of the Roman general-turned-Christian, only to fumble the last word: faith. This happens at the emotional climax of the speech, as the Coens’ cut between the film-within-the-film and their own. But rather than break the cinematic illusion of Hail, Caesar! A Tale of the Christ, this intercutting eliminates the distance between film and set, the Roman general and Baird. In reference to the self-evident holiness of his newfound God, he implores his fellow Romans to embrace the light, and in that moment he is also Baird addressing the rest of the cast and crew. However, before he can finish his line, before he can ask them to embrace “a truth we could see if we had but––”, the director yells cut and the moment crashes back into the mundane. Baird becomes the bumbling actor once again.

The film is constantly shuttling between irreverence and sincerity, and not just with comical supporting characters like Baird. Tonally, Eddie’s story reads more like a hagiography than a historical biopic. Some scenes present him as but one man, struggling heroically against the incompetence of those around him, an incompetence that isn’t so much rooted in a lack of professionalism as a lack of faith. When Baird comes back from his abduction, spouting communist rhetoric against the studio, Eddie, in true McCarthyite fashion, treats him less like an insubordinate employee and more like a member of a parish on the verge of apostasy. “You're gonna give that speech and believe every word of it!” he exclaims as he slaps Baird back to his senses. Eddie doesn’t merely demand that Baird do his job, but that he actively “have faith in the picture.” In using socialist politics to criticize Capitol Pictures’ structure and head, Baird committed not just an unprofessional, or even criminal, transgression, but an unholy sin.

The inseparability of American capitalism and religion is also defined in the scene when Eddie summons the clergymen to assess the “tastefulness” of the picture. It doesn’t take long for Eddie to let his motivations slip, confessing subtly that the holy men are there primarily to ensure the film does not get boycotted, an outcome the studio would not be able to afford. The whole meeting feels like a joke, its very premise a delirious setup: three priests, a rabbi, and a studio head walk into a room and discuss the nature of God in a motion picture. They bicker relentlessly, only to conclude that it actually doesn’t matter. They won’t picket the film. The studio head moves on.

Eddie does, however, seem tempted by an offer to leave the studio for the Lockheed Corporation, the weapons company whose bloody name today (Lockheed Martin since 1995) is synonymous with American military campaigns in the Middle East, including the devastating war in Yemen. Eddie’s conundrum, too, is framed in terms of faith. So pious is his commitment to the studio that he asks his overworked priest for advice on whether he should leave his job for Lockheed, framing it as a theological question. Would God forgive him if he walked away from his calling?

Eddie has no moral qualms with the actual operations of Lockheed. The guilt he incurs at the mere thought of leaving the studio is more rooted in his sincere belief in the divinity of the movies. The Lockheed representative mocks Eddie’s job, dismissing movies as “only make-believe.” Nayman put it best: “The decision facing Brolin’s efficiency expert is…between two industrial complexes: one devoted to the creation of fake worlds, and one whose endgame is the possible destruction of this one.” Yet Eddie himself does not deny his role as a craftsman of trickery, as evidenced by his assertion to the gossip columnist that people do not, in fact, want the truth as much as a compelling story. Eddie’s ultimate rejection of Lockheed comes down to his zealous commitment to that dream factory. He is not actually against what Lockheed does because his loyalty to the head of the studio is not so different from his commitment to the state. The only difference is he fights not to protect American territory, but American identity—or rather the studio heads’ conception of what that means. The man from Lockheed was right to identify Eddie as a qualified candidate for military work, but he failed to understand that he was asking a priest to leave the cloth to enlist in the army.