Immerse Yourself:

On Sensory Stories at Museum of the Moving Image

By Sean Flynn

Sensory Stories: An Exhibition of New Narrative Experiences runs through July 26 at Museum of the Moving Image. The exhibition was conceived and organized by Future of StoryTelling.

Before reaching Museum of the Moving Image’s core exhibit, Behind the Screen, which boasts media artifacts ranging from a restored Edison kinetoscope to the iconic 1990s video game Sonic the Hedgehog, visitors must pass through an angular white lobby accented with neon blue light. Rather than harkening back to the history of moving images, the space seems to invite us to dwell momentarily in their possible futures. Upon my visit, this impression is underscored moments after I check my coat, when I am greeted by the sight of a five-year-old girl wearing an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset, flapping her outstretched arms on an awkward mechanical contraption that looks like a cross between a bird and a massage chair. Behind her, a flat-screen monitor displays the stereoscopic first person view of her virtual flight over Manhattan. A few minutes later, the simulation comes to an abrupt end and the girl clambers down off the apparatus, grinning and bewildered.

It’s easy to speak in the abstract about the dramatic changes that digital media technologies have wrought in our lifetimes, but this scene reminds me that such long-term disruptions are usually made up of small, individual moments of discovery. For my generation, those moments include the first time sitting in front of a personal computer, playing a video game, browsing the Web, or picking up a smartphone. Will that girl remember her first experience with virtual reality in the same way? The “new-ness” of new media tends to fade quickly as certain technologies and forms become taken for granted in our everyday lives—particularly for those too young to remember a world before them. On the other hand, not all new media are predestined to reach the ubiquity of the smart phone. History is littered with what Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey Pingree have called “failed media,” innovations that either arrived before their time or weren’t able to create a market that facilitated their spread.

The “Sensory Stories” exhibit at Museum of the Moving Image is a playground for visitors of all ages to have personal encounters with emerging media technologies, novel interfaces, and experimental narrative forms that haven’t yet stabilized as familiar conventions. The basic premise of the exhibit suggests that technologies like virtual reality are in the process of transforming the way we experience stories, “bringing the body, mind, and senses,” in the words of the Museum’s executive director, Carl Goodman, “into a new relationship with the moving image.” The dozen-plus works on display throughout the Museum from now until July 24 represent a broad cross-section of developments in the rapidly evolving field of immersive media, including VR experiences, interactive films and installations, games, iPad apps, object-based interfaces, and responsive art works. The only thing uniting these disparate forms is their use of digital technology to invite more active, bodily engagements with media than “traditional” forms of storytelling like films, books, or radio.

Watching visitors’ reactions to Birdly, the VR flight simulator (which closes on June 7), it’s easy to see how such immersive media experiences can capture our attention, engage our senses, and even move us emotionally in ways that are not possible in other media. But do they help us tell better stories? Given the nascent state of the field, it can be hard to discern when techniques like interactivity and participation engage audiences more deeply in a story, and when they get in the way. At a time when “disruptive innovation” has become a sort of mantra, there is a greater risk of using technology for its own sake—a shortcut for generating buzz—rather than as a tool that meaningfully serves the needs of the story or the audience. Though “Sensory Stories” is curated by the organizers of Future of StoryTelling, an annual summit that explores these matters, the exhibition wisely avoids any straightforward predictions of what the future might hold. Rather, it suggests that storytellers working in immersive media are still exploring the possibilities and limitations of their new tools, searching for a language and grammar in which interactive interfaces might become natural, intuitive—even taken for granted—aspects of the “narrative experience.”

Following the pattern of other recent festival-based showcases of interactive storytelling, virtual reality seems to be the most popular attraction at “Sensory Stories.” On a sunny Sunday afternoon, a room equipped with four Oculus Rift VR viewing stations is crowded with a diverse mix of families and young couples waiting patiently for their turns to try on one of the headsets. In contrast to new media programs at festivals like Sundance, IDFA, and Tribeca, where growing hype around VR films has translated into queues that can last hours or days, my wait time for these films is typically 20 minutes or less.

Pulling on the headset for Chris Milk’s Evolution of Verse, I suddenly find myself a disembodied point in space, floating over a photorealistic 3D-rendered mountain lake at sunrise. A distant trail of smoke reveals itself to be a 19th-century locomotive, which emerges from the trees, turns directly toward me and accelerates across the water. Just before the moment of “impact,” the train dissolves into a flock of birds that swirl over my head, unfurling a tapestry of multicolored banners. Amidst a triumphant flourish of arpeggiated piano chords, I lift off the lake and fly through a tunnel in the sky that leads to the interior of a womb, where I briefly circle around the head of a larger-than-life unborn child. These somewhat heavy-handed allusions to both the Lumière brothers and Stanley Kubrick suggest that we are living through a moment analogous to the birth of cinema at the end of the nineteenth century—and that this new medium heralds a new era for humanity full of radical artistic possibilities.

Image: Evolution of Verse: courtesy VRSE / Future of StoryTelling

Milk, known for boundary-pushing interactive music videos like The Johnny Cash Project and The Wilderness Downtown, has certainly become one of the most outspoken proponents of virtual reality’s artistic potentials and its ability to foster empathy. At a recent TED talk, he described traditional cinema in antiquated terms, a medium comprised of “rectangles played in a sequence” that has remained unchanged in its basic structure since the days of Edison and the Lumières. “The frame is a window,” Milk explained. “I want you through the window on the other side.” In another VR film playing at the museum, Clouds Over Sidra, Milk attempts to take viewers “through the window” to the Za’atari camp in Jordan, currently home to 84,000 Syrian refugees. Following the familiar format of a human rights advocacy documentary, the film profiles a young girl living in the camp. We hear her describe her struggles and dreams, cutting between scenes from her daily life at home and in school. Rather than experience this world as a two-dimensional rectangular frame, the 360-degree video allows me tilt and turn my head to look in all directions, taking in whatever details of the environment interest me as the linear story unfolds. Contrary to the claims of some VR evangelists, I never fall under the illusion of heightened reality, immediacy, or “presence.” If anything, I remain acutely aware that my body is still sitting in a museum gallery in Queens, and that I am tilting my head and twisting my torso in full view of other museum visitors. At the same time, the freedom to choose where I look does seem to impart a more total sense of place than I might have sitting at the back of a movie theater. When the film ends, I am tempted to play it back again—not to re-experience the story, but to let my gaze wander to unexplored corners of this spherical world. Perhaps VR’s real potential lies more in this heightened experience of “fly on the wall” voyeurism than a feeling of “walking in someone else’s shoes” empathy.

In Evolution of Verse and Clouds Over Sidra, my only agency as a user is choosing where to look in a scene and my interactions ultimately have no consequence for the outcome of the story. Some immersive media projects, however, explore the potentials created by the Web and interactive screens to bring users into the story, asking them to make decisions about the path they travel through it or giving them some stake in the outcome. Possibilia is an interactive narrative film that falls into the latter category. Directed by the creative team The Daniels, the film depicts the angsty breakup of a young couple played by Alex Karpovsky and Zoe Jarman. As a tense argument unfolds between the two, a menu of thumbnails representing sixteen branching storylines expands at the bottom of the wall-mounted touchscreen display. Accepting the invitation to interact, I reach out and tap on one of the options. A beat later, the setting suddenly shifts to another room. This edit happens mid-sentence, but the dialogue continues seamlessly across the two scenes. The only difference is that the actors’ body language now seems more at ease, the emotional tone a bit lighter. Has my decision placed their argument on a path toward reconciliation? Near the end of the film, the branches of the narrative begin to collapse until we reach a final, seemingly inevitable, conclusion. As a user, there’s something rewarding about this “choose your own adventure” technique and the invitation to edit the film while watching it. The nonlinear structure also helps underscore the story of a breakup and its countless decision points. But I still find it difficult to make motivated decisions or know for sure if my actions have any effect on the outcome of the story, apart from changing the venue in which the couple’s argument unfolds.

*****

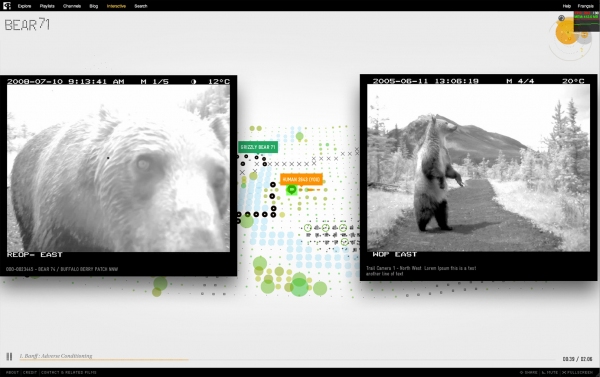

Many of the projects at “Sensory Stories” are built for the iPad. Unlike VR, a much-hyped but still largely inaccessible medium, interactive works created for tablets have an established distribution platform and tend to build incrementally on our engagements with existing media, like books, films, and games. 1979 Revolution Game uses game mechanics to recount a dramatic chapter in Iranian history, alternating between story sequences and game elements in which the user is asked to take part in unfolding events—for example, by photographing a protest from a rooftop. In John Lennon: The Bermuda Tapes, the user can advance the story of Lennon’s fateful sailing trip through a Bermuda storm using horizontal parallax scrolling, pausing to listen to Lennon’s recordings from the trip or moving on to the next chapter. Welcome to Pine Point and Bear 71, two web documentaries produced by the National Film Board of Canada that might now be considered part of the interactive storytelling canon, also use the iPad to add interactive elements to an otherwise linear narrative. Originally released in 2011, Pine Point tells the story of a now-abandoned mining town in Canada’s Northwest Territories, weaving together first-person narratives, archival photographs and video, and an ambient soundtrack into an evocative nostalgia-tinged multimedia scrapbook. At the core of Bear 71 is a linear, eighteen-minute audio story about a grizzly bear being collared and tracked in Banff National Park. Users are invited to navigate through an abstract, interactive grid of data points that represents the various ways the park’s animal life is surveilled by humans using digital technology. While these interactions have no impact on the story, the impressionistic design of the interface helps to underscore the project’s themes.

Image: Bear 71: courtesy National Film Board of Canada

Like Birdly, some of the “narrative experiences” at “Sensory Stories” place more emphasis on experience than they do on narrative. Mimicry, the interactive artwork by Emilie Tappolet and Raphael Munoz, features two framed digital displays with “paintings” that respond to the viewer using facial recognition technology. While viewing a mountain landscape, for instance, I can open my mouth to create a rainstorm or close my eyes to bring nightfall. As I approach the image of a sleeping baby, rendered in 3D, it awakens and creepily mimics my head movements and facial expressions. Though they don’t convey any explicit story, these responsive paintings point to one of the defining features of interactive media: at the same time they engage our senses, they are also sensing us, observing every click, swipe, tilt of the head, or change in facial expression.

The works at “Sensory Stories” demonstrate the myriad ways that new technologies can be used to surprise audiences, capture their attention, and in some cases, draw them deeper into a story. Yet these techniques also force audiences to make decisions about where to look, what to click, or how quickly to advance through a narrative. The central challenge with immersive media experiences, it seems, is that these modes of engagement place greater cognitive demands on users, asking them to simultaneously learn the interface and absorb the story. By attempting to transcend the limitations of traditional media forms, many of these experimental works run the risk of wrapping a story around the affordances of the technology rather than adapting technologies to the needs of the story.

Of course, these are not new problems. In the early days of cinema, the apparatus itself was the main attraction and audiences came first to witness the spectacle of moving images projected on a screen. It took decades before the techniques of montage and mise-en-scène matured into the cinematic conventions we now take for granted. Perhaps we need to move beyond the spectacle of the “apparatus” of immersive media technologies before we can use them to tell artful, absorbing, emotionally powerful stories. For that to happen, artists will need to find ways to make the technology disappear and design interfaces that become as intuitive and transparent for future generations as the cinema has been for ours.

Image at top courtesy Thanassi Karageorgiou / Museum of the Moving Image