Out There, In Here:

Genevieve Yue on the films of FIDMarseille in First Look 2015

Before We Go plays Sunday, January 11; I Touched All Your Stuff (A Vida Privada dos Hipopótamos) plays Friday, January 16; Our Terrible Country plays Saturday, January 17; Alone with My Horse in the Snow, Axel Bogousslavsky plays Sunday, January 18, at Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2015.

The First Look festival is the most adventurous program in the Museum of the Moving Image’s calendar, and its expansion this year, in number of films, geographical reach, and formal experimentation, indicates a healthy trend toward curatorial risk-taking. Part of its growth includes a selection of nonfiction films from FIDMarseille, co-programmed by MOMI Chief Curator David Schwartz, Assistant Curator Aliza Ma, and FIDMarseille director Jean-Pierre Rehm (following a carte blanche program Rehm organized last year). Though nominally a documentary festival, FIDMarseille seems chiefly concerned with challenging the form and the expectations that are brought to it. Often these are works that blur the line between fiction and documentary, shift the investigative or observational focus to unusual subjects, or in some other way complicate the relationship between the filmmaker and those being filmed. These are strategies commonly associated with the avant-garde, and if anything, the growth of both FIDMarseille and First Look speaks to the increasingly diffuse spread of avant-garde approaches into areas that were once more rigidly distinct, namely documentary film and the narrative feature.

This formal innovation is apparent in many works, including Before We Go, by Jorge Léon. The film is an extension of the director’s work at a palliative care center, where he hosts creative workshops for the patients, many of them terminally ill. For Before We Go, Léon relocated his therapeutic work to the space of the majestic La Monnaie Opera House in Brussels. Paired with actors, choreographers, singers, and artists, the three patients Michel Vassart, Noël Minéo, and Lidia Schoue wander the theater loosely charged with exploring the motif of death. Even if some elements are overly stagy—Noël is saddled with the allegorical companion, Death, or a tap-dancing Simone Aughterlony in a skeleton suit—the relationships between those who have entered the stages of dying, and the artists tasked to assist them in rendering creative form for their experience, are deeply felt and observed. In response to his deteriorated sense of perception from disease and drug use, Michel affixes color gels to the windows, aided by Benoît Lachambre. In a directly literal way, these panels offer a different way of seeing, literally coloring the street scene outside. The most powerful scene belongs to Lidia, whose illness makes it painful for her to move, and choreographer Meg Stuart. They begin their improvised dance together with hugs and caresses. As Lidia turns her head, or asks to be lowered to the ground, her expression is one of calm surrender. Here, art may not much resemble life—aside from a few early shots of Michel, Noël, and Lidia in their apartments, there’s little realism in the film—but neither does life try to resemble art. Instead, the opera house gives these lives, these performances, or the indistinct place between them, a frame, a place where we can marvel at the little “ah!” sounds Lidia releases with happiness as she stretches her arms.

Many of the FID picks could be called character studies. Alexandre Barry’s Alone with My Horse in the Snow, Axel Bogousslavsky is in some ways a more conventional portrait than that of the trio in Before We Go, though the individual it describes, the actor and hermit Axel Bogousslavsky, is hardly typical in any sense. The film is shot in deep blue shadows, an effect of the interior of Bogousslavsky’s cabin, though the surrounding winter forest is also cast in a darkened shade. This lends the study of Bogousslavsky a rarified and even surreal air, especially as he lies atop his horse. He speaks little, except in voiceover musings on nature, art, and solitude, during which time the camera carefully examines, in close-up, the contours of his ascetic world: a bowl for soup, a large wooden table on which he draws and writes, and a small stuffed animal that lies on his pillow. Though an old man, Bogousslavsky has a childlike air, his saucer-shaped eyes recognizable from a clip of his younger self performing in Marguerite Duras’s The Children. How he got from that film, or his twenty years spent in the theater with director Claude Régy, to this isolated woodland existence, is left unexplained. We’re given a hint of his former life, when he regards a photograph of himself as a child. Holding the small, scallop-edged image of a boy with the same saucer eyes, he wonders, “Why do things happen? Do they already exist before they occur? Maybe that’s what this little child is seeing.”

Maíra Bühler and Matias Mariani’s I Touched All Your Stuff (A Vida Privada dos Hipopótamos) also examines an unusual individual. Early on, the filmmakers explain that they are interested in prisoners convicted in foreign countries, in this case the American Christopher Kirk, who is being held on drug trafficking charges in Brazil. What distinguishes I Touched All Your Stuff from other contemporary documentary portraits is the seemingly limitless access they’re given to Kirk’s trove of computer files, including cell phone movies, photographs, emails, texts, and instant messages. It’s an overwhelming amount of material. Like many of us, Kirk archived every aspect of his life, but the question on which the film turns is whether these digital traces offer any true insight into Kirk. Though he’s described by friends as “the last innocent guy in the world,” there’s something shifty about him, something too rehearsed about his story, which he tells from within a Brazilian prison. The narrative involves a classic femme fatale set-up: seeking adventure, Kirk traveled to Bogotá and immediately fell into the clutches of the mysterious and alluring “V,” a Japanese-Colombian woman responsible for his demise. While they dated, various lies and inconsistencies began to surface, and, suspecting that V was involved in drug smuggling and prostitution, Kirk hacked into her email and confirmed his worst fears. If spying on his girlfriend seems dubious, Kirk drops other hints of his shady behavior, like his collection of books about con artists, and an IM exchange with one of V’s ex-boyfriends where they talk about her sexual demeanor. This is less a tale of amour fou than a defense of straight-up “nice guy” misogyny, where, in Kirk’s account, he comes off as clean while the corrupt and corrupting woman is “a crazy bitch.” It also fails to explain how, many years later, Kirk wound up in prison. The filmmakers admit that Kirk keeps “a kind of distance from himself,” but it’s one they’re unable, or unwilling, to bridge. The film’s title refers to a prank played on Kirk, in which one of his friends wrapped the interior of his Seattle apartment, and all its contents, save a photo of V, in aluminum foil, leaving a note that said “P.S. I touched all your stuff.” The line is sinister, but it’s possible that Kirk got the last laugh. Though he gives Bühler and Mariani access to all his digital stuff, he remains untouchable.

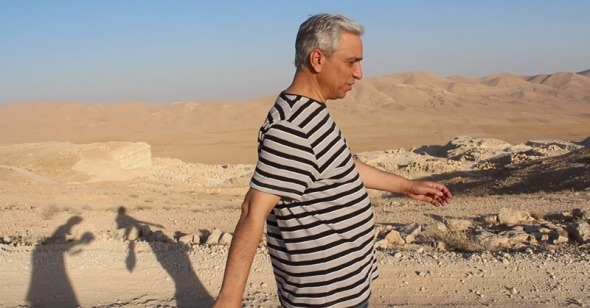

Our Terrible Country, by Mohammed Ali Atassi and Ziad Homsi, stands out as not only the best of the FID films (it won the grand prize award in the FIDMarseille International Competition) but also the most daring. It depicts the journey of the Syrian intellectual and dissident Yassin al-Haj Saleh as he travels from the liberated and decimated city of Ghouta to his hometown of Raqqa (now controlled by ISIS), and, finding it impossible to move freely through Raqqa, to Istanbul, where he awaits word of his imprisoned wife. His companion is the young revolutionary and one of Our Terrible Country’s filmmakers Ziad Homsi. Theirs is a journey without a set course. Saleh previously spent sixteen years in prison for his revolutionary activities, but the uprising that took place two and a half years ago, and the resulting civil war, was not the one he’d worked toward. Early in the film Homsi asks him: “Is this the freedom you want?” Saleh laughs. “I would have preferred a more chic and less costly freedom. However it seems this is the price we’re forced to pay.”

With Saleh’s constant and generous smile, it is sometimes easy to forget that Our Terrible Country takes place in the midst of war. As he traverses the country, he comports himself with gravitas, whether lying under a canvas tarp for shade, or answering a reporter’s questions via Skype. With a friend, he laments the ineffectual role of intellectuals in the revolution, now overrun with ISIS, or what he calls its “cancerous growth.” Yet Saleh is encouraged by the enthusiasm of the younger generation who might bring about another revolution still. This promise is carried by those like Homsi, though he, like Saleh, fears most immediately for incarcerated relatives. After a prolonged separation, Saleh and Homsi reunite in Istanbul, embracing each other and crying for the hardships both of them, and all Syrians, endure. For the moment, they wait and agitate from the outside. “I am part of the Great Syrian exodus, and of this Syrian hope of return,” Saleh says in voiceover as we see him walk through a leafy forest. “Even though it resembles a slaughterhouse today, this is our country, we have no other.” Our Terrible Country takes us to this impasse. But it is more than a vessel, and in some ways more than a film.

This is the best of what any film, documentary, fiction, or somewhere in between, can hope to do. Like Homsi and his comrades, who are “fighters and at the same time . . . journalists,” the film itself is a revolutionary chronicle, a portrait of solidarity, and a statement of hope that the obstacles encountered today might eventually be overcome.

Photos: Our Terrible Country (top), courtesy Bidayyat for Audiovisual Arts; Alone with My Horse in the Snow, Axel Bogousslavsky, courtesy Les Films du Taramin