by Damon Smith

A couple of weeks ago, the press officer for the Stockholm International Film Festival got in touch with me with a generous offer, wondering if I’d like to travel to Sweden at their expense and cover this year’s programming, an international meld of features, shorts, and documentaries, most making their Nordic debut. After a glance at the competition films (many of which I’d seen at the 2010 Berlinale or elsewhere) and sidebar sections (Latin Visions, Asian Images, Twilight Zone), I decided there was enough here to chew on: a dozen or so world premieres, works-in-progress by up-and-coming Scandinavian filmmakers, and plenty of entries from Cannes, Venice, and Toronto. Besides, I’d never been to Stockholm, a beautifully preserved archipelago city with cinematic associations stretching from Victor Sjöström and Greta Garbo to Ingmar Bergman and Stellan Skarsgård. Never mind that it would be wet and wintry, or that the sun sets sharply at 3:30 p.m. in late autumn. The thought of stuffing myself on foreign cinema and braised reindeer meat a few days before Thanksgiving seemed to be the only antidote to post-election November blues.

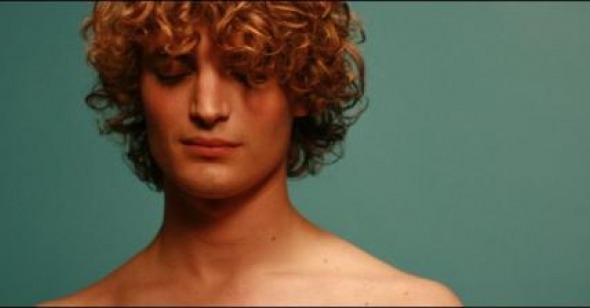

Twenty-one years on, the Stockholm festival remains dedicated to its founding mission under director Git Scheynius: the nurturing of fresh young cinematic talent from around the world. So Les amours imaginaires (a/k/a/ Heartbeats), the sophomore feature by Cannes-fêted Québécois wunderkind Xavier Dolan (I Killed My Mother), a mere tyke at 21, was a sensible choice for the curtain-raising competition film. A sensual and stylized depiction of obsessive, unrequited love, the film trails a pair of lovelorn friends, Marie (Monia Chokri) and Francis (Dolan), who fall hard for tow-headed Nicolas (Niels Schneider), a new acquaintance whose audacious Greco-Roman beauty (flashes of Michelangelo’s David are paired with his androgynous face in one dance-party scene) and carefree, bedroom-ready manner drive them into a stinging rivalry for his affection. While Dolan’s film will play well with those who savored the youthful drift and polyamorous anomie of Alexis Dos Santos’ Unmade Beds or Alfonso Cuarón’s megahit Y tu mamá también, any talk of a genetic redesign on Truffaut’s Jules and Jim is far too generous. (Blank to the point of vanishing, Nico is a foil for the turmoil that envelops his admirers, not a fleshed-out stand-in for Jeanne Moreau’s complex Catherine.) Undoubtedly, there is something to be said for Dolan’s precociously dazzling visuals and sassy, Almodóvar-esque color schemes, as well as his impeccable choice of music (Italian-Egyptian chanteuse Dalida’s “Bang Bang” energizes a series of bliss-out slo-mo sequences), but there is often less than meets the eye here, especially when all the flirtatious foreplay and anguished longing add up to is a sly, slow-resolving irony.

Self-bemused to an equally frustrating degree is Bernard Rose’s slap-happy Mr. Nice, which purports to be the rollicking life story of Howard Marks, the Welsh-born, Oxford-graduated drug smuggler whose illicit international dalliances with Kabul warlords and the IRA made him one of Britain’s most infamous countercultural figures from the 1970s to the early Eighties, when he was nabbed by U.S. authorities. (The film is based on Marks’s bestselling 1996 memoir of the same name.) As played by raffish actor/musician Rhys Ifans, Marks is a good-natured rogue whose life changes when he’s introduced to hash at university (Rose shifts the film from archival black-and-white to color after his first toke), then stumbles aimlessly into bootlegging after trying to make a go of it as a strait-laced teacher. (Okay, whatever.) Never mind the ham-fistedness of the tall-tale-telling conceit or Rose’s dumbfoundingly cheeky decision to cast the ragged, middle-aged rocker Ifans (who bears a striking resemblance to his real-life counterpart) as Marks at every stage of his life, including youth. If you forget all about film artistry (and really, you must) and surrender to the maladroit frenzy of scenes-from-the-life-of-an-unapologetic-dope-fiend, then you might find yourself intermittently entertained by such piffle. At least David Thewlis pops up for a scene-chewing turn as arms-dealing IRA soldier Jim McCann, a hot-tempered miserabilist with a penchant for porn and silly code names. Then there’s poor Chloë Sevigny, who, as Marks’s hippie wife Jane, materializes over a Go board to utter vacuously raunchy dialogue amid a blaze of spleef smoke (“What’s wrong with something that makes you want to fuck?”) and then—poof!— turns into her dull-as-Betty-Crocker wifely double on Big Love. Crikey!

Bringing us back to the real world in more sense than one is Bhutto, a Sundance 2010 entry that pays tribute to a soulfully courageous, yet troubled world leader screening in the fest’s Documania section. That is Benazir Bhutto, the Western-educated female politician who was twice elected prime minister of Pakistan before she was assassinated in 2007, presumably by political opponents. Although the focal point is Bhutto herself, eerily heard narrating important moments in her colorful and tragic life via a trove of scratchy sounding, previously unreleased audio tapes, the doc encompasses half a century of bloody regional conflict while revisiting the specific tragedies (murder, imprisonment, exile, assassination) that have befallen the entire Bhutto clan. Guided at warp speed through a short, informative history of the tumultuous Pakistan state in the film’s first half hour, we observe the Muslim nation’s transformation after the 1947 partition under the charismatic leadership of president Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a force of (mostly secular) modernization who once had the nerve to tell John F. Kennedy that if he were American, he’d be installed in the White House. The story then shifts to Benazir, a Harvard- and Oxford-matriculated student who returns home to campaign for democracy after her father is executed in 1979, following a military coup led by Gen. Mohammed Zia ul-Huq. Her determined resistance, skillful politicking, and rousing oratory are evident in the archive footage and television appearances, as well as in the testimony of Peter Galbraith, Condoleeza Rice, college pal Arianna Huffington, and especially close friend Mark Siegel (one of the film’s producers). Unfortunately, it doesn’t always flow smoothly in the editing, especially in quick-mix interludes early on, like the one that splices images from Bhutto’s student days with scenes of Sixties civil-rights protests. Such compression tries too hard to force the association, and the mawkish Cat Stevens hit “Wild World” only makes it worse.

Yet unlike most hagiographers in thrall to their subject, Duane Baughman and Johnny O’Hara do strive to complicate Bhutto’s mystique as a reformer and feminist, giving voice to those, like her niece Fatima, who maintain that Benazir and her husband Asif Ali Zardari (who appears in the film) ran a deeply corrupt administration, lining their own pockets with the spoils of lucrative, nepotistic business deals. (She blames them as well for the violent death of her father, Murtaza, Benazir’s more radicalized brother, who was murdered facing down his estranged older sibling in a return-from-exile political campaign.) Effective as an elegy and as a crash course in the knotted politics of Pakistan, one of only eight nuclear powers in the world, Bhutto memorializes a paradoxical, larger-than-life presence on the world stage whose family history was hand-wringingly Shakespearean, and whose legacy helps contextualize the chronic hypocrisy of U.S. policymakers toward this beleaguered nation.