The Right to Choose

By Farihah Zaman

Ex Machina

Dir. Alex Garland, U.S., A24

Though it is hardly the first film to tackle our society’s anxious fascination about the inevitable day that robots take over the earth, Ex Machina stands apart, largely thanks to a feminist agenda that sits alongside its more standard preoccupations with the nature of consciousness, what makes us human, and what rights, as humans, we are entitled to, regardless of origin. The film begins with Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a reserved young programmer at the fictional search engine startup BlueBook (clearly modeled on Google), winning a contest to visit the home of the company’s founder, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). The boss’ life is unique in a way that is both exciting and unnerving; Caleb is flown to an isolated location by helicopter, then unceremoniously dropped in the middle of a field and told to “follow the river” for miles. When he finally arrives at Nathan’s behemoth glass-and-iron complex, there are no windows in his sleeping quarters, and every door in the place opens (or, perhaps more importantly, does not) according to security clearance. Then there is the matter of Nathan himself, the kind of guy who thinks his success and genius entitle him to bully and provoke, and who spends most of his nights getting drunk alone and most of his days “detoxing” via exercise that has given him a stocky, intimidating boxer’s build.

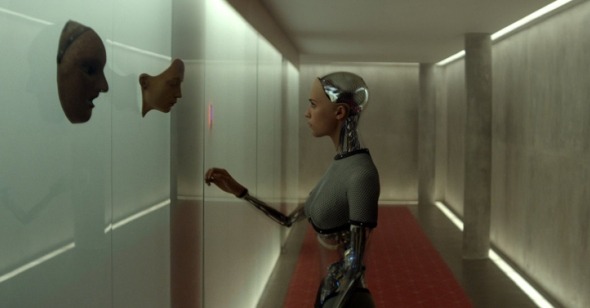

As it turns out Caleb was summoned not just to keep the mad scientist company but also to evaluate his latest project, an android named Ava, the most advanced piece of artificial intelligence ever created. Caleb is immediately attracted to the “machine,” a fact that clearly disturbs him. She is made visibly robotic, partially transparent, with some Apple-product-style sleek, shiny bits not yet covered with panels of synthetic flesh, and yet for Caleb her human attributes—the fact that she has hobbies, asks questions, feels anxiety, jokes, pouts, smiles, flirts—overcome the sensory reminders of her artificiality. Predictably, Nathan proves to be withholding and deceptive throughout the film, but it is unclear to Caleb whether he is merely secretive or if his intentions are far more sinister. As Ava opens up to Caleb—romantically, but also about her captivity, mistreatment, and the past models Nathan has disabled (or murdered, depending on how you look at it)—Caleb grows determined to help her escape.

Caleb’s sessions with Ava are loaded with a curiosity and wonder that give way to sexual tension, leaving the young man confused and perturbed. And the more Ava seems to desire Caleb, the greater is his belief in her humanity, as if he’s learned the lessons taught by stories from Pinocchio to The Fifth Element, which claim that the ability to love is what truly makes us human. Silly Caleb: Ava’s proximity to humanity lies not in her desire to learn and engage, as he initially feels, or even her ability to flirt or deceive, as he later coms to believe—such behaviors are easily mimicked, and conversely, not necessarily present in all humans. In Ex Machina, the robot’s humanity lies in the fact that she has her own reasons for exhibiting all of the aforementioned behaviors, intentions behind her actions that may even go against the nature of her programming. This idea—that consciousness resides in the ability to desire—is not wholly original either; that alternately thrilling and horrific moment when A.I. develops emotion or intention is a science fiction staple from 2001 to Bicentennial Man. But what Ava wants also differs from past iterations of this parable. She seeks not the liberation of her entire people, the survival of a new robot species, world domination, or human enslavement. She is not acting under the instructions of her overlords, and her desire is awakened by neither pure congenital malice nor the transformative power of love. She wants nothing more than freedom, and for no one but herself.

There have, of course, been other rebellious female A.I. in cinema, like Metropolis’ tellingly named False Maria. There have also been films that question (or perversely indulge in) the power dynamic between male creator and female creation, like Weird Science, and films that ponder the ethics of romance across a kind of owner/owned, organic/artificial divide, like Her. Perhaps the fixation dates back to the story of Adam’s Rib. What sets Ex Machina apart is that gender and sexuality constitute its primary focus; general questions of consciousness are merely threads woven into a tapestry about the politics of male-female relationships. It is of tantamount importance that Ava is a woman, that all previous iterations created by Nathan were women, and that they are, as conscious, female humanoids, under the subjugation of their creator, who doesn’t see this as problematic because he views them as less than. This is sadly not unlike many women’s situations IRL. Even with a sensitive, well-meaning guy like Caleb, there still exists an uncomfortable power dynamic, one that Ava might be evening out through the use of sexuality and manipulation, an equally uncomfortable prospect. These questions, and Caleb’s doubts regarding her intentions, would exist even if Ava were made of flesh and blood.

Ex Machina is the directorial debut of Alex Garland, the screenwriter behind 28 Days Later and Sunshine, so this man knows from sci-fi, having a built a reputation for well-plotted, action-driven films with an unexpectedly robust intellectual undercurrent. Ex Machina follows suit in both writing and direction. Garland was wise to set ninety percent of the film in one location, as it gives him a highly controlled environment, and the camerawork feels purposeful and precise. The film’s clean, sparse aesthetic matches its minimalist narrative, which hinges on just three characters. This means, of course, that the performances of Vikander, Gleeson, and Isaac are crucial.

Likely drawing on her background in ballet to imagine what the motion of a cyborg might be like, Alicia Vikander entrenches herself firmly in the uncanny valley, seeming just human enough to entice yet just robotic enough to unnerve. Gleeson, for his part, plays the guileless naïf and the quietly unhinged rebel with equal believability. Oscar Isaac steals the show (perhaps unfairly so, given Vikander’s subtler work) for his delightfully broad nerd-jock-hybrid. The only laughs of the film come from Isaac’s several perfectly delivered one-liners and visual gags, which usually combine a sense of levity with the grotesquely offensive, like when he performs a choreographed, Soul Train–inspired dance routine with his cyborg sex slave Kyoko while ignoring Gleeson’s horrified expression. (Isaac’s dance here brings to mind Sam Rockwell in both Charlie’s Angels and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.) While his breakout role in Inside Llewyn Davis saw him play a scruffy underdog, Isaac’s performances in Ex Machina and 2014’s A Most Violent Year have unearthed his potential as a morally complex movie villain. Nathan is a smug yet charming scumbag whose social gifts spring not from a love of the human mind but a keen, amused understanding of its weaknesses and vulnerabilities, a desire to experiment and manipulate. How telling that the one person able to re-create human life is himself missing traits we often most—and perhaps falsely—associate with humanity. It comes back to the idea that it is not the extent of our love or hatred that determines the extent of our humanity.

In some ways Ex Machina may be considered a feminist film by sheer dint of our low standards, the scarcity of stories that explore female desire beyond the realm of sex and romance. Disney’s Brave, for example, felt revolutionary in the animated princess realm solely because it is about a mother-daughter relationship rather than a romantic one. In the end of Ex Machina, Ava’s decision to leave her sweet, manipulated accomplice to rot in that Brutalist prison—an action upsettingly human in its calculated cruelty—completely shatters the film’s false construct as a love triangle; it was never about love to begin with. It also shifts perspective from the male gaze —Caleb watching Ava—to her view of herself and the options set before her. It highlights the possibility that even the viewer has failed to contemplate her intentions, consider her desires. And as in Brave, it pushes the narrative away from the expected question—which man will our heroine choose?—to the subtly subversive one: should she choose any man, and who will she be on her own terms?