Mon Oncle d’Amérique

Julien Allen on Unforgiven

When you glance for the first time at the original one-sheet poster for Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951) your occipital lobe should immediately detect a familiar pose. Kirk Douglas is bending over his co-star, Jan Sterling, as if he were holding her in his arms. Her head is plunged back, and her eyes are closed, as if she is anticipating his kiss; her body language depicts ecstasy, just like that of Vivien Leigh in the poster for Gone with the Wind (1939) or Audrey Hepburn’s in the poster for Roman Holiday (1953). But when you look more carefully you can see that Kirk Douglas is not kissing Jan Sterling, nor is he about to kiss her. He is in fact strangling her with a fox fur scarf.

Ever since I embarked upon the task of writing this piece, I keep finding myself re-watching American films that inadvertently contribute to the story I want to tell. And as a foreigner I watch almost every film about America through the same prism now. Wilder’s dark-as-coal exposé of post-war America is one of a dozen formative films that could have qualified as the subject of this essay, had they arrived in my life at the right time, had they produced the effect on me which Unforgiven (1992) did on first viewing. Lumet’s Twelve Angry Men (1957) made me a cinephile, but it didn’t flick a cultural switch for me, only a philosophical one; Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) speaks to me about America, but only in retrospect and from an outsider’s point of view; Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) bridges that chasm between Americanism and universality as all great American art does. The hardest question is how can I separate America from the America I see in the movies? How can I separate America from the movies at all?

***

In 1961, while a contract actor on TV’s Rawhide, Clint Eastwood sat one day in a Los Angeles theatre watching Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. His reaction—judging by his own typically concise account—would have been in keeping with the theme of this symposium: “Gosh, it’s like a western.” He was of course right: Kurosawa was a devotee of American westerns (as much as he was of pulp gangster thrillers, one of which—Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest—he used as the basis for Yojimbo’s screenplay) and no doubt enjoyed the irony of several his own samurai pictures successfully being refashioned as such. But beyond this, Eastwood was drawn to Toshiro Mifune’s character in Yojimbo, Kuwabatake. Not only because of his smoldering presence and martial arts brilliance, but also for what he perceived as the unusual way in which this protagonist was presented to the audience: a lonely ronin, disillusioned, selfish, crass, and unkempt. When faced with the prospect of starring in an English-language remake of Yojimbo three years later, Eastwood’s reaction was light years from Rick Dalton’s agonized soul-searching depicted in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (2019). The Italian-financed adaptation, A Fistful of Dollars (1964) was filmed in Spain and directed by Sergio Leone, who would become one of Eastwood’s directorial father figures. The 30-year-old Eastwood was tapped for the part after his Rawhide co-star Eric Fleming had passed and he did not hesitate.

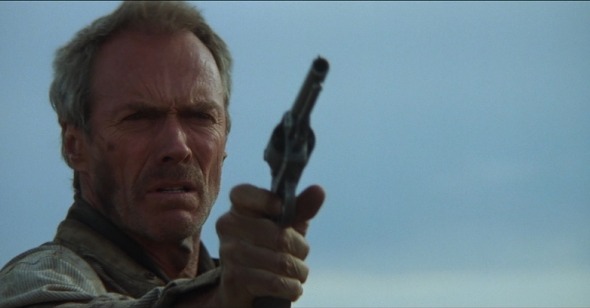

Looking back now, his seemingly uneventful but ultimately iconic transition from clean-cut, white-hat hero in Rawhide to unshaven cheroot-chomping black-hat antihero in A Fistful of Dollars would not only come to define the mythology of Clint Eastwood in front of the camera, but it would also serve as the structural foundation of Eastwood’s public persona forevermore. Over the years, an irresolvable dichotomy would develop between his humane, upstanding American decency and his apparent macho predilection for frontier justice. This would endure, through the Dirty Harry controversies, the debates in the ’70s and ’80s about Eastwood’s worth as a director, through his critical peak in the 1990s, all the way to the idiocratic tyranny of the 21st century’s Twitter landscape and its gradual, drip-drip extinguishment of moral and political complexity from the cinephilic vocabulary. Eastwood calls himself a libertarian (is there a more “Old West” concept than this?) while his favorite movie is William Wellman’s 1943 leftist, anti-death penalty rule-of-law classic The Ox-Bow Incident, starring Henry Fonda in a precursor to his role inTwelve Angry Men. It seems that when it comes to an artist thinking, acting and being more than one thing in America, a man’s got to know his limitations.

When I was growing up in the south of England in the late 1970s, my own limitations were mostly pecuniary. I never even imagined I would set foot in America. A close school friend was taken to Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and—bent double with envy—I dared not ask my parents to consider doing the same for me. America was too far away, and while we’re talking of limitations, I didn’t dare to dream. Cautious pessimism is all the rage these days, a home-made therapeutic technique for sensible adults in the age of Trump. But it’s certainly not recommended for children—in any era. “Dirty” Harry Callahan’s sardonic aphorism “A man’s got to know his limitations,” soon became a personal mantra (I missed the sarcasm and read it at face value), which served me well for a time but which I’ve long since struggled to cast aside even if—unlike Jeff Goldblum’s callow partygoer in Annie Hall—I’ve never forgotten it.

From a young age I thought I understood something of America, because like nearly all English kids I watched imported network television on weekends: Sesame Street on Saturday mornings, Starsky and Hutch and The Dukes of Hazzard in the daytime, Taxi and Hill Street Blues in the evenings. Hollywood—a European enclave with its industry constructed from the ground up, à l’américaine—would program my earliest cinematic experiences, but they were not especially American ones. Disney’s animated classics were a repackaging of quintessentially European literature (Perrault, Grimm, Milne, Collodi, Kipling, Andersen) while their live action output was a pure cultural soup, cherry-picking a little something from everywhere and signifying nothing. The dawning of the blockbuster (an American concept in industrial terms only) gave my parents American stories like The Godfather (1972) and Jaws (1975) but more formative for me were supra-cultural examples like Star Wars (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981): they told stories of fantasy and of outer space. They may have been made with American talent (and a good deal of British talent too, both being filmed at Pinewood Studios, about half an hour from where I live now), but they didn’t connect me, or any of the people around me, to America. As a teenager whose film education began in French (through my French mother) sitcoms like Cheers and, later, Roseanne opened significant American windows, but their formal artifice did not let in quite enough air. While America has always been superficially all around us in Britain—from our TV through our training shoes and breakfast cereal to our police sirens—back in the pre-internet age we still felt a bit like strangers, like two nations separated by a common language, per Shaw’s maxim. Friends who visited America in the 1980s would spin tall-sounding tales of being served burgers in your car by a waitress on roller skates and of a “home box office,” where there were hundreds of films on TV to choose from (as if that could ever happen). As a teenager I felt almost as culturally distanced from America as I did from Russia or Japan.

The only screen entertainments I can point to in retrospect which felt uniquely, supremely American, were westerns: repeats of Maverick, Bonanza, and The High Chaparral on the TV, and, occasionally, low budget B-westerns in the cinema, programmed before the main attraction. My TV set provided the grown-up versions too: Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954), Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), and John Wayne’s The Alamo (1960) were all enjoyed solo, on a 12-inch screen, lying on the floor of my parents’ bedroom. The violence in these pictures was primordial. Its threat seemed to hang in the air, such that whatever the tone of a scene, the promise of a sudden lurch was ever present. And the violence also made me feel grown up. The men were confident; the good guys were better at violence than the bad guys. It was the violence that distinguished films from television for me.

***

Unforgiven (1992) came at a time when American studios were scarcely producing westerns anymore. It wasn’t quite the first major “new western” of the period: Kevin Costner’s multi-Oscar-winning outlier Dances with Wolves (1990) had led the charge and signaled to the industry that westerns, while culturally unfashionable, could find audiences and critical acclaim. Nor did Unforgiven “reinvent” the western, certainly no more than dozens of other films such as The Left-Handed Gun (1958) or Soldier Blue (1970) which had been awarded that questionable accolade before it. French critics talk of “reinvention”, American ones of “revisionism”—terms too frequently used when describing original or successful genre films, when a more accurate concept would be “renewal”—and neither were really Clint Eastwood’s style. He had made a few moderately successful period westerns during the preceding decades—High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976),and Pale Rider (1985)—and to anyone not paying close attention (which, in critical terms, was most people) they could have been straightforwardly categorized as bland star vehicles, featuring Eastwood operating safely as actor-director within the creative environment that made him his fortune.

It was only in 1988, with his rough-hewn but sublime Charlie Parker elegy Bird, that he was elevated to recognized authorial status. To many European critics—notably Dilys Powell of the Sunday Times, whose reviews were of profound significance to my teenaged self—Bird was a consecration of Eastwood’s obvious talent as a director, but to some U.S. critics it still represented something of an overreach. (For Pauline Kael—hardly Eastwood’s most enthusiastic champion at the best of times—Bird was nothing less than an insult to the medium itself.) Nevertheless, Bird’s comparative critical sweep distinguished its reception from such earlier, unfairly overlooked personal films like Bronco Billy (1980) and Honkytonk Man (1982). In contrast to his mainstream fare—in which his lead characters were sometimes almost metaphysically superhuman—these personal films had the opposite fixation, telling poignant tales of lovable losers. This concern for the welfare of the little man on his uppers chimes strongly with the one pillar of American culture that was actually taught to me at school: Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Like Bronco Billy and Honkytonk Man before it, Bird—the story of a genius, tragically laid low—took in no money.

In returning to the western genre, Eastwood stepped up his ambition while resigning himself to a certain authorial insignificance. It seems peculiar, given his two dozen films since and counting, to think that at the time, he believed Unforgiven might be one of his last films as a director. Whether he intended it or not, one of the things he achieved with Unforgiven was to renew our acquaintance with a form of American classicism, while telling a story that could chime with modern sensibilities. At the dawn of the 1990s, after a decade of Reagan-era cinematic bloodletting via Carolco and Simpson-Bruckheimer action productions starring Mel Gibson, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Sylvester Stallone (franchises whose popularity could be directly traced back to the success of Eastwood’s own Nixon-era creation, Dirty Harry), Unforgiven seemed a quaint throwback to the Truman-era politics of Henry King’s The Gunfighter (1950), because in many ways it was. Eastwood dedicated it to his two creative masters, Don Siegel (the man who did most to encourage him to turn his hand to direction) and Sergio Leone.

Directed from an original screenplay by Blade Runner’s script doctor David Webb Peoples—not hitherto considered a writer of especial repute, despite his own fascination with art cinema—Unforgiven is the sanguinary adventure of an aging outlaw and killer, William Munny (Eastwood) who is persuaded out of self-imposed retirement by a visually impaired young gunslinger calling himself “The Schofield Kid” (Canadian debutant Jaimz Woolvett). In return for a fee, they are tasked with crossing three states to execute two cowboys who brutally disfigured a woman called Delilah Fitzgerald (Anna Thomson) in the town of Big Whiskey, Wyoming. Deputized to their cause is Munny’s old partner in homicide, Ned (Morgan Freeman). Standing in their way is the formidable “Little” Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman), the malignant sheriff and mob boss/CEO of Big Whiskey.

The lavish green plains and mountainous plateaus of Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming form a backdrop to this solemn, unrushed journey back into the heart of darkness—shot for the most part in the high country of Alberta, Canada and on the stunning flats of Sonoma in Northern California (an area of outstanding natural beauty I am delighted to say I have since been able to see with my own eyes). These landscapes are lovingly filmed with a pointed intimacy and slowness. The aesthetic approach is one of serenity and contemplation, enticing the audience into the space, to ride alongside the protagonists, all the better to experience what they are feeling. There is little sense of the epic, symbolically transcendental grandeur of John Ford’s The Searchers or William Wyler’s The Big Country, nor any of the relentless environmental hostility of Howard Hawks’s Red River or Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. The waxing tension at the center of Unforgiven is fully interiorized by the characters, while the open country stares back at them, oblivious. The “classicism” inherent in these gently unfurling images is simply constituted by characters who are given space to breathe and audiences who are given time to think and feel.

And this classicism is far from trite. Eastwood palpably understands that familiarity, citation, and reference are not sufficient. While some shots in Unforgiven carry deliberate visual echoes of classic western cinema—such as the slow static take of the young free-spirited Kid, sent on his way at first, riding off into the horizon as Munny, old and caged, watches him intently through the grill of his pigsty—most of the film’s compositions are more directorially understated: closer to the storytelling immediacy and rawness of a Siegel than the audiovisual fireworks of a Leone, whose own demonstrative style Eastwood chose to deploy only at the film's climax. By taking the time to let these characters and locations settle, Eastwood cherishes the memory of great western storytelling while creating a powerful symbolic backdrop for the script’s real thematic modernity.

A significant critical observation about Unforgiven (which really isn’t said often enough) is that it’s a man’s film in which women dictate the vital elements of the action. Women provide the spark to the tinder; and they fan the flames each time the blaze threatens to go out. Even if one discounts the opening epigraph attesting to Munny’s conversion to a peaceful Christian existence out of respect for his dead wife’s wishes, it is easily forgotten that the entire, incendiary plot of the film—which features misogynistic atrocity, political upheaval, revenge tragedy, torture, a devastating rite of passage, moral annihilation, and squalid, bloody murder—is ignited by a woman laughing at the size of a man’s penis. It is the women of Big Whiskey’s billiard bar–cum–brothel who are constrained to place a bounty on the aggressors’ heads because Little Bill—in a bout of political self-interest worthy of Pontius Pilate—refuses to administer adequate punishment. He orders Delilah’s attackers to pay a horse each, to the women and the brothel-keeper. The women wanted the men hanged. Instead of accepting their lot, the women, led by the formidable Strawberry Alice—played by Eastwood’s then wife, Frances Fisher—mobilize to administer their own reprisals.

The emotional positioning of attack victim Delilah—who, slightly disconcertingly, is the spitting image of the victimized Jan Sterling in Ace in the Hole—represents a prominent step forward in Eastwood’s authorial attitude towards women, within a body of work which constantly betrays his often-uncomfortable fascination with them. His directorial debut, Play Misty for Me is both a well-crafted wronged-woman revenge thriller in the mold of Adrian Lyne’s inferior later effort, Fatal Attraction, and a fine-granular exploration of men’s sexual anxiety, with an eerily compelling female antagonist, Evelyn (an extraordinary turn by Jessica Walter). From then on until Unforgiven, women who appeared in Eastwood’s films were nearly always placed in default positions of conflict and confusion vis-à-vis the principal male characters. So, while it is unquestionable that Munny’s decision to come out of retirement in Unforgiven is partly animated by his own inability to completely close the door on his former self, for the first time Eastwood’s antihero protagonist is irrefutably and unconditionally dedicated to the female cause: justice for the women of Big Whiskey.

It is the other men in the film—Little Bill, the cowboys, the brothel-keeper—not Munny, who are confused about where women fit in. To them, the treatment of humans as tradeable assets is part of the circle of life. Given that the status quo, however unjust, protects their way of life, it should be tolerated, not to say protected. Witnessing Munny’s loneliness, even Ned (Freeman) suggests to him at one point that he might go into town “and get himself a woman.” Munny demurs. “It ain’t right, buying flesh.” (An upsetting sequence later will feature Ned being whipped by Hackman’s Little Bill—its overtones of slavery prevalent but unmentioned, like Ned’s ethnicity. Almost as if one cause—racial emancipation—for all its obvious parallels, should not be allowed to actively get in the way of another: female emancipation). The bounty Munny is offered for the job plays no part in his decision; his ultimate sacrifice is for these women he doesn’t know. It will be a sacrifice more immense than he can have predicted.

In a lacerating scene towards the film’s climax, Munny and his “employer” Delilah finally meet. The power of this moment has nothing to do with politics and everything to do with the human instincts and emotions which should inform all of politics. The characters of Munny and Fitzgerald present as two tragic, lost souls: one metaphorically scarred, the other literally. This coincidence struck me on first viewing as the emotional centerpiece of the film. Munny—a ruthless murderer, a man of action—fumbles awkwardly in his attempts to reassure Fitzgerald that his refusal of her offer of “an advance on his payment” (sex) is not down to her disfigurement, but instead out of loyalty to his wife (whose death he keeps secret from her). In the 30 years since that first viewing, this exchange alone (“you ain’t ugly like me”) feels to me as raw and devastating as any single sequence I have seen in American cinema. It awakened me to what it can do that other art forms cannot (in terms of its holistic impact: aesthetic, emotional and intellectual), and to all the levels (from the superficial to the profound) in which it can reach down inside of us and grab us. Numerous great American movies (Johnny Guitar, Only Angels Have Wings, The Best Years of Our Lives) achieve this miraculous effect too, I can see this now. But for me, in 1992, Unforgiven was the film that first joined the dots: between American sensibilities and European ones, between action and contemplation, between mainstream Hollywood releases and the art house, between the “movies” and the “cinema”—it seemed to unite all motion pictures under one umbrella.

Incidentally, Eastwood would go on to direct three more films explicitly centered on women—The Bridges of Madison County (1995), Million Dollar Baby (2004) and Changeling (2008)—all of which attested to a clear relaxation of the macho attitudes he had displayed and explored up until Unforgiven. By the time his antediluvian character in The Mule (2018) arrives, unable to resist an arched eyebrow and a smile in the direction of a gang of leather-clad lesbian bikers, Eastwood is exercising the right to dip back into his subject by sending up his own defaced image.

But the modernism of Eastwood’s approach to classical western cinema in Unforgiven is not merely embedded within the film’s thesis, narrative pace, and cinematography. It is also there in the way the film treats Eastwood’s own cinematic and real-life persona. Stories create myths…and movies do so too, with remarkable efficiency. The Dollars trilogy, Kelly’s Heroes, Dirty Harry and its sequels—these forged the myth of Clint Eastwood. What Unforgiven does, finally, is to confront that myth with reality.

Eastwood, like Munny, is old (61 at the time of shooting); he is in the background; his notoriety and his way of life have essentially ebbed away; but his legend lives on undiminished, strengthened perhaps by the passing years but distorted and embellished, as legends often are when their progenitors are inactive or dead. “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” says Maxwell Scott (Carleton Young) in Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). In Unforgiven the character of WW Beauchamp, as played by Saul Rubinek, embodies this autochthonous western concept of “fake news”—famously explored by Wilder and Walter Newman in Ace in the Hole and by Orson Welles and Herman Mankiewicz in Citizen Kane—as a memoirist who accompanies the fraudulent “English Bob” (Richard Harris) and later simply jumps ship to Little Bill, after the latter has viciously expelled the former from Big Whiskey. Unforgiven is also about how dangerous mythology can be and how difficult it can be to shake off.

Even if the character of Munny represents a classical archetype, he exhibits many facets of Eastwood’s own real-life persona: his questionable reputation (as a person, as an actor, as a director) and his deeply misleading mythology, not to mention his fervent desire to do something different. Perhaps this desire for change is designed to influence the development of that very mythology (as his previous picture, White Hunter, Black Heart tried to do for John Huston, even if Huston’s own final film The Dead, had already thrown that mythology a curve). More likely, it is to get closer to something that Eastwood felt mattered. When interviewed in London at a public event organized by the Guardian newspaper in 1993, Eastwood spoke—in his inimitably unobtrusive manner—of wanting to make a film of violence where the violence meant something, on account of “too many of [his] films having used violence gratuitously in the past.”

In Unforgiven, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Faced with the need to kill, the players consider it at length, they act…and then whether they go through with it or not, something in them is forever changed. Part of Unforgiven’s classicism—its reliance on ancient dramatic conceits—lies in its quasi-Shakespearian focus on how man’s flaws direct their progress (Munny’s physical frailty, the Kid’s near-sightedness, Ned’s impotence when tasked with ultimately pulling the trigger). But here is also where its modernism surfaces. The primary raw material of American cinema has been violence ever since 1903, when Justus D. Barnes opened fire on the audience with a Colt 1878 Double Action in The Great Train Robbery, but rarely has it been so tangibly decorticated from a genre for which disposability of human life is almost a watchword. As the Coens reminded us recently with The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), the West may not be all of America, but it has always been America’s greatest storybook. Ken Burns’s elegiac PBS miniseries The West (1996) confirms as much, pinpointing it as “the place where America’s story is told.” The American West is a series of stories of belief and opportunity, drenched in violence. John Wayne said westerns were the only purely American art form. I sometimes think that maybe the movies themselves—the simple telling of stories on film for mass entertainment—are a purely American art form. And if we only think about it cursorily, even today, do we not always expect violence when we “go to the movies”?

A woman’s curse in Unforgiven is to be forced to deal with being a victim of violence. A man’s curse is to be forced to cope with being the perpetrator of it. It turns out that one of man’s biggest “flaws” is that killing doesn’t actually come naturally to him—it has to be taught and can very easily be unlearned. The insurmountable challenge in Unforgiven is for all to make their peace with the necessity and omnipresence of violence. Ned retires because he cannot carry out the contract: he is subsequently captured, tortured, and killed. In an excruciating sequence, the Kid does in fact kill one of the cowboys at close range (the Kid cannot see any further than a few feet) while his victim is on the toilet. After long contemplation, this character—the Kid—who has existed thus far in the story only to play up to his own image as a killer, decides he cannot face killing again. Munny, by contrast, presumes to have conquered violence by understanding it, normalizing it and leaving it behind, as if it were a relationship or a job. He tells the Kid as the latter reels from his deed: “Hell of a thing, killing a man. You take away all he’s got.” “Yeah, well, I guess he had it coming.” says the Kid, searching in vain for some moral comfort or absolution. Instead, he just gets Munny’s withering reply: “We all have it coming, Kid.”

Today’s America contains deafening echoes of the America of 1992. The Los Angeles riots erupted in April of that year, over the acquittal of four police officers for assault and excessive force on the person of Rodney King. King endured repeated beating: over fifty blows to his torso and face, the breaking of his leg and the apparently sadistic use of a 50,000-volt Taser TE86 stun gun to his chest, causing severe burns. All of this occurred as he surrendered peacefully following a suspected drunk-driving incident. The ensuing uprising in downtown Los Angeles led to over 60 deaths, 2000 injuries and 12,000 arrests.

Audiences—and certainly critics—would have undoubtedly felt an emotional correlation between Unforgiven’s deep thematic dive into violence and the scarring effect of the Rodney King uprisings, but in Los Angeles alone—even ignoring the rest of America—the message could just as well have resonated in 1943 (Howard Hughes’s The Outlaw; the Zoot Suit riots) and 1965 (Leone’s For a Few Dollars More; the Watts riots). Violence isn’t just a fundamental part of America’s history, it feels to me like an ever-present component of American life, expected, ingrained, protected by its Constitution. In January 2021, the Capitol’s invaders, whipped into violent combat with quasi-religious fervor by their calamitous wrecking ball of a leader, spoke of lynching their political opponents and thought of themselves as patriots.

American cinema at least reflects this reality and debate obviously persists as to whether it does more. Because of his status as the most prominent and unapologetic purveyor of American screen violence of recent times, Quentin Tarantino has been called upon so often to defend it that he has grown sick and tired of the question. His most quoted intervention evokes the persistently dubious distinction between fictional violence and real: “People ask me, ‘Where does all this violence come from in your movies?’ I say, ‘Where does all this dancing come from in Stanley Donen movies?’ If you ask me how I feel about violence in real life, well, I have a lot of feelings about it. It's one of the worst aspects of America. But in movies…violence is cool. I like it.” As glib as this sounds it is inescapable. The ending of Unforgiven addresses this philosophical conundrum head on, infusing the climax with horrifying ambiguity. Munny consecrates his own corruption, even after fulfilling his contract, by riding into Big Whiskey to avenge Ned by slaughtering Little Bill and his men. In so doing, he extinguishes whatever good conscience he had left by breaking the covenant he had made to his wife—a form of moral suicide when one considers what went before. In the final analysis he is weak; powerless to resist his own nature and more tragically still, mortgaging his hard-learned values to the overpowering sentiment of revenge, thereby denuding his life of what little worth it had left. But revenge is intrinsic to cinematic storytelling because it represents our most primal human expression of justice. Eastwood ultimately gives us, his audience, what we have always come to expect from the Man with No Name. In so doing he confronts us—without judging us—with the inherent moral deficit of the western genre and of the movies themselves: their natural, instinctive reliance on violence as entertainment, when violence is the ruin of everyone.

***

It is customary to talk of auteurs as having complete command of their subject, but sometimes too little respect is paid to those filmmakers who make great films in a manner that evidences the precise opposite—their absence of a comfort zone, their struggle…or in Eastwood’s case, just their humility. Eastwood once punctured an effusive Melvyn Bragg on a South Bank Show special on the UK’s ITV network with the withering line, delivered as politely as it is possible to imagine: “I’m a filmmaker, I’m not finding a cure for cancer.” Uncertainty is precious in filmmaking, as so many debut films attest, but Eastwood’s discomfort in Unforgiven is at the other end of the spectrum from the upstart innocence of the great American debuts like Citizen Kane, Blood Simple, Badlands, Duel, Eraserhead, and Reservoir Dogs. It is in the fear of the final film, of having lost what one once had; the fear of no longer mattering, of no longer weighing on the world; of no longer being able to pull the trigger.

Maybe what chimed most with the 21-year-old me was the Kid. When he visits Munny at the beginning, he is like a cocky but innocent film buff looking for a brush with stardom, or like a young writer or producer wanting to collaborate with a famous director whose reputation he reveres. But the icon is not ready and not sure. Consequently, one of the most beautiful things about Unforgiven for me—and we should really be urged to watch it in this way—is that it is not a confident film. In its direction, it is infused with self-doubt, caution, and uncertainty. It is stripped of demonstration and clamor, falling back on limpid, linear storytelling—the most precious essence of American moviemaking—and the belief, not to say the hope, that this will be enough. In the image of its protagonists, it proceeds with deep, heartfelt unease toward its devastating conclusion. Out there in the dark, as the rain hammers down, truth and meaning lie in wait too.