Simple Men

by Michael Joshua Rowin

W.

Dir. Oliver Stone, U.S., Lions Gate

Among the series of advertisements for Oliver Stone’s W. is a poster that reflects how the overwhelming majority of Americans currently imagine their president. It shows Josh Brolin as George W. Bush seated at his desk in the Oval Office, his hands a hammock of fingers supporting a demoralized, hanging head, his face darkened by shadow. In light of the unfolding financial crisis—where Bush has failed to display even a modicum of fortitude in assuring a worried populace about their country’s economic institutions—the W. poster accurately captures the Commander-in-Chief as an overwhelmed shell of a leader, caught in the headlights of a disastrous history he himself has helped create.

Only a single scene in the actual film replicates this poignant evocation of the farcical tragedy that is its title character. Toward the end of W., as the Iraq War turns into an unmanageable, chaotic, and deadly occupation, Bush is asked at a press conference to evaluate any mistakes he has made since 9/11. Bush stumbles in coming up with his answer, transcribed verbatim from the real one given on April 13, 2004: “I don’t want to sound like I haven’t made no mistakes, I’m confident I have. It’s just that I haven’t—you really put me on the spot here, John. Perhaps I’m not as quick on my feet as I should be in coming up with one. But, uh . . .” Stone refuses to play the scene for laughs. Scanning around the room of dumbfounded reporters and nervous members of the president’s inner circle, the camera reminds us not only of Bush’s arrogant lack of introspection, but how it has been perceived. The public has wondered in amazement how such a man could have ascended to this level of power—and been left guessing as to whether Bush’s obliviousness might very well be a pandering put-on—while his enablers have just hoped he could fool enough people to keep the charade going until things somehow pan out.

Not coincidentally, this is the only scene in W. containing traces of the long dormant style Stone practiced in the Nineties, the height of his controversial career. When Bush hesitates, Stone cuts to inserts of the character at a different angle and in an even more desperate pose, a sort of dramatic magnification slightly outside the linear narrative action. It’s a minor echo of the signature aesthetic that has turned many off to Stone, especially his more bombastic forays into hallucinatory montage such as The Doors and Natural Born Killers, but it’s the aesthetic that brought a uniquely kinetic sensibility to his other historical biographies, especially Nixon. In their colliding of symbolic and atmospheric cutaways, newsreel footage, and dramatic reenactments these films created multi-sourced portraits as dense and exciting as peak Nicolas Roeg.

The rest of W., however, is shockingly flat, both in presentation and in insight. A bright, sunshiny sheen, for example, accompanies the vast majority of this deceptively slight film’s images. Longtime cinematographer Robert Richardson, a vital collaborator during Stone’s heyday, is now clearly, sorely missed. Instead of the rich, mysterious shadows that draped Nixon in menace and paranoia, W., as shot by DP Phedon Papamichael, rejects moody atmosphere in favor of a conspicuous blandness that in turn places emphasis on performative mimicry (though only Thandie Newton’s Condi Rice could pass for the real thing) and obnoxious musical commentary (a finger-picking guitar rendition of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a non-Louis Armstrong version of “What a Wonderful World” that serves as an unwelcome reminder of the cheap irony of Bowling for Columbine). For all of the film’s muckraking pretensions, it’s the cartoonish Bush of a thousand talk-show host imitations that wins out, with Stone providing an appropriate but still embarrassingly one-dimensional visual correlative.

W. fares little better story-wise. Stanley Weiser, screenwriter of Stone’s Wall Street, has little to say about Bush that anybody who’s been paying the minimum amount of attention to events during his administration or who’s explored the background of our 43rd president doesn’t already know. Alternating between Bush’s first-term Iraq invasion and his transformation from callow frat boy and prodigal scion of an aristocratic Texan family to “improbable” born again leader of the United States, W. provides curiously haphazard biographical highlights that play more like punchless SNL sketches than the grand Shakespearean narratives of JFK and Nixon. Perhaps Bush doesn’t deserve such epic treatment—at the very least, there’s no proper “ending” that could serve as a definitive, cathartic capper—but even mediocrity demands elucidation, and in this sense W. is enormously bereft of ideas about Bush’s character and what he means to our national identity.

W. rests on the premise that Bush has forever contended with father George H.W. (James Cromwell, thankfully not trying to contend with Dana Carvey), who both reprimands and coddles Junior’s dissipated ways by getting him off the hook for his reckless behavior. Bush believes Poppy, as he calls the patriarch, favors brother Jeb (Jason Ritter, only seen in the early years) more than himself, a perceived favoritism that stokes petulant jealousy. Yet he’s also disappointed with dad’s gutless approach toward presidential matters, an approach he then corrects with a more bellicose handling of foreign affairs (channeled from the intermittent insolence and rage that overcomes him in moments of frustration, as when he rams his car into a garage door) once he moves into the White House. It’s an obvious Oedipal conjecture that overshadows the ideological motivations behind “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” while reducing a likely more complex family dynamic—Barbara Bush (Ellen Burstyn), naturally, wears the pants—to psychological clichés.

Brolin does his damnedest to make Bush human. He has the accent, the gestures, and the attitude down cold, but his too-handsome face unavoidably contradicts the character’s willful ignorance with a rugged stoicism only Bush’s supporters—or whatever remains of them—pretend the man possesses. What really sinks W., though, is Weiser’s lazy writing, with Stone acting as enabler. One would never mistake Stone for a subtle filmmaker, but there’s a difference between the sublime corniness of a director who can with a straight face include a line like “We took drugs to expand our minds—not to escape” (from The Doors) and the weak imagination of a director content with the run-into-the-ground Bushisms cut and pasted into nearly every exchange of W. The infamous “Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice . . . won’t get fooled again” is here taken out of context and grafted into a meeting among Bush’s cabinet, but for what reason other than to tickle the viewer with a familiar bit of idiocy? After eight years of Bush chuckling at his own ineptness, more probing tactics are in order.

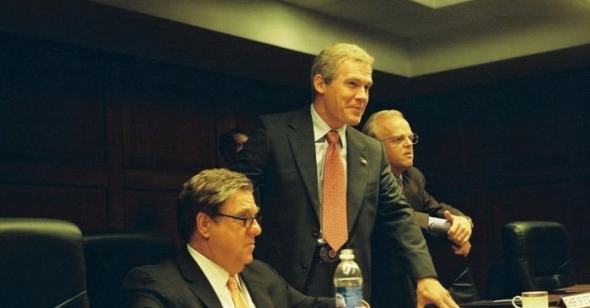

Weiser’s Bush-era greatest-hits samplings equally smacks of a blunt political consciousness. It’s next to impossible to take seriously the film’s attempts to uncover its antihero’s conservative convictions and often gullible susceptibility to influence (with Tony Jones’s revenge-minded Karl Rove and Richard Dreyfuss’s oil reserve-gobbling Dick Cheney playing devils on shoulders) when the pretzel choking incident receives screen time over the 2000 election, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, all notably absent. Formative interactions with other characters are likewise limited to demanding but vulnerable Bush Sr., understanding and nurturing Laura (Elizabeth Banks), and, in two sincerely handled scenes, spiritual advisor and born-again evangelist Earle Hudd (Stacy Keach), but other than that there’s not much exploration of the orbits circling planet W. War room meetings during the build up to the war play like high-school debate classes, with Colin Powell (Jeffrey Wright) the lone (and malleable) voice of reason against the predictable cabal of Cheney, Rove, and Rumsfield (Scott Glenn). Compared to these op-ed columns in screenplay form, Bush’s stubborn TV-movie determination on the path to the White House seems incisive and illuminating.

With Bush’s presidency drawing to a close, W. gets the first pop culture crack at judging his legacy—and lands a woefully soft punch. What Stone and Weiser fail to recognize is that Bush’s pratfall of power wouldn’t be so remarkable if it didn’t so conspicuously mirror America’s increasing conformity, proud isolationism, and unashamed mediocrity. Nixon ends with its disgraced protagonist addressing a portrait of rival-even-after-death John Kennedy: “When they look at you, they see what they want to be. When they look at me, they see what they are.” It’s a grace note hit perhaps too hard, but it nonetheless gets the point across—the country’s been implicated along with the president, for even if many of its citizens didn’t support him, it made him who he was and allowed him to reign. W.’s view of history, on the other hand, is insulated. Bush exists apart from us (unlike in Stone movies past, news footage inserts stand off in parentheses rather than interacting with original material), his good ol’ boy charm that apparently won over the crowds only named dropped in lifted phrases—“the kind of guy voters want to drink a beer with,” sayeth Rove—rather than explored in depth as the contemporary breed of political charade it is. Now that the country is hanging its head along with Bush, that image is obsolete, except in 95% of W.