Mule Variations

by Eric Hynes

Maria Full of Grace

Dir. Joshua Marston, U.S., Fine Line Features

Ever since Dickens metamorphosed realism into a metaphor, and class differences gave cause to document how the other half lives, the idea of authenticity has taken on an evaluative importance that often supersedes aesthetic concerns. Telling of dreams forestalled by economic and social inequalities, these are stories helmed by tragic heroines—characters both beautiful and damned. That their suffering is as symbolic as it is “true to life” is the signature paradox of realism: our (anti-)heroine’s suffering is both authentically real and typically tragic. Maria Full of Grace, a fine first film by Joshua Marston, is an effective and faithful child of the genre. Following the lead of contemporary realists Ken Loach and John Sayles, Marston explores the ways that poorer communities within and without western society shoulder the burden of certain demands of market capitalism. Marston’s film literalizes this pressure by focusing on Colombian drug mules: those recruited to transport ingested cocaine packets on commercial flights to New York. The human face for Marston’s dramatization of this dreadful practice belongs to—needless to say—a young woman named Maria. As embodied by newcomer Catalina Sandino Moreno, Maria graces nearly every frame of the picture, and our emotional investment in her plight relies almost exclusively on how we respond to her beautiful, blank face. As if shouldering familial, societal, and criminal (let alone gastro-intestinal) burdens weren’t enough, Maria also has to carry the picture.

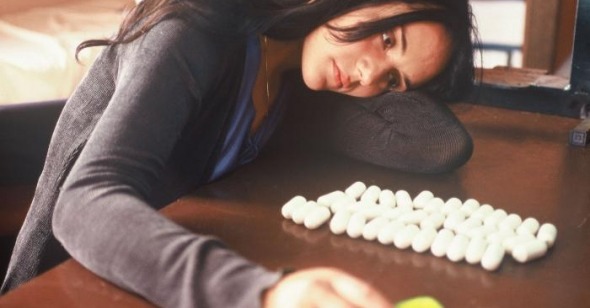

At the outset Maria lives in a small town north of Bogotá and works at a rose plantation as a thorn stripper. Though jobs are scarce and her position and its salary are enviable, Maria, already fed up with the tedium and finger pricks, quits when her superior refuses to let her use the bathroom (but not before the superior forces her to wash clean roses ruined by her own vomit). Unsupported by her mother and sister—both unemployed and unmarried with children—who rely on Maria’s checks to run the house, her rebellion only intensifies. She’s bored with her petulant boyfriend, feels abused by her family, and, like any 17 year-old, starts looking for her own way in the world. But she’s quickly confronted by unshakable realities: she’s pregnant, and her family really does need her to support them. Unwilling to marry a boy she doesn’t love, and unwilling to return to the plantation and swallow her pride, she instead hitches a ride with a charming stranger and they motorcycle to Bogotá. Instead of seeing about a cleaning job, she’s enticed by the stranger to consider being a mule; it’s easy work, he says, you get to travel, and there’s a wealth of money involved. Although it feels like Maria agrees a little too quickly to meet with the drug trafficker in charge, screenplay structure demands that Act 2 get started immediately, lest the audience grow restless. Only 30 minutes into the film, she, and we, are immediately faced with the prospect of ingesting prune-sized rubber-encased cocaine pellets by the dozen.

Though such narrative precision has a way of making decisions feel predetermined, Maria Full of Grace benefits from these jarring transitions, its point-to-point speed deepening our sense of Maria’s impulsive character. And it’s her actions, rather than expressed ideas or feelings (of which there are few), that endear us to her. Moreno’s blank, dignified gaze invites us to look along with her, taking in everything and figuring things out as we go. As schematic as social realist films are, most rely on deep characterization to garner empathy for their doomed women with bad judgement. But rather than a character study, Marston frames Maria’s plight more like a Mametian thriller of tension and headlong conflict.

Maria’s motivations for putting herself in such great danger and in such shady hands so suddenly are underexplored, but the particulars of drug muling are reported in minute detail. Maria stands before a mirror and teaches herself to ignore her gag reflex by swallowing oversize grapes whole. The cocaine pellets are packed and triple-wrapped in the fingers of rubber gloves and tied tightly with dental floss to prevent bursting in the body and killing the carrier. She fasts on the day before her trip so that the precious cargo doesn’t pass from her; when it does just that, mid-flight to New York, she retrieves the errant pellets from the toilet and spreads toothpaste over the rubber to swallow them again. Toothpaste as antiseptic gets a second cameo when the mules pass the pellets in safety and hand them over to squeamish drug running thugs. Since the film deals with a topical international crime scenario and we’re in the realm of anthropological realism, standards dictate that the success of the film depends on these details. I’ve no reason to question their authenticity. I only wish that the supporting characters—Maria’s friend Blanca and an older woman, Lucy, both recruited as mules on the same flight to New York—weren’t so clearly concocted to illustrate these details and dramatize the various consequences of volunteering for this work; I wish I didn’t know which characters—like partners in cop movies—were doomed at first sight; I wish I weren’t reminded of Top Gun while immersed in the Colombian underworld. But these wishes confront me with the paradox of the genre, and why should Maria Full of Grace be any different? That a unique situation should feel so familiar is perhaps the point. Some live. Some die, horribly. Some get through customs and some go to jail. Some learn from their mistakes and forge a new life for themselves. Others don’t, but films don’t get made about them.

Maria makes more bad decisions in Newark and then in Queens, but is fortunate to meet Lucy’s benevolent and wise older sister, Carla. Portrayed by Patricia Rae, whose brief but moving characterization energizes the last third of the film, Carla’s life represents a more mature approach to self-sacrifice, one that requires the slow, lonely immersion into a foreign country of greater opportunity. I’m glad that Maria doesn’t have to die for her sins; most contemporary realists have evolved the narrative this far since the 19th century. Though not as delicate, confident, or perfectly balanced as Paul Pawlikovsky’s Last Resort from 2000 (in my opinion the pinnacle of this brand of tourist realism), Maria Full of Grace doesn’t shoot at easy targets or even bother looking for bad guys. Although some characters are more full of grace than others, they all retain a certain dignity. Maria Full of Grace is a compelling film, and inside the entertainingly tense thriller and wrenching melodrama are depictions of lives and scenarios previously unseen in a North American film. I’m grateful, and better for knowing more about these people than I had previously known. I credit and admire Joshua Marston for this. So I hope I don’t sound dismissive when I ask: Who besides Marston—and me, the viewer, in my casual, personal-development way—really benefits from Maria Full of Grace?

Somebody anticipated this question, at least in part, because the press kit for the film mentions that locals were employed whenever possible and that old buildings were renovated for the sake of the production (though because of political unrest, the film was shot in Ecuador rather than Colombia). For all I know, every dime of profit is going towards developing the local economy in Colombia, or lobbying Congress to rethink the War on Drugs. I doubt it, but it’s not what I’m crowing over. With the exception of the Dardennes’ Rosetta , whose filmmakers covered territory much closer to their home and effected a major change in policy in Belgium, these tourist realist films seem to be for us and not for them. Marston’s project is praiseworthy, his film is very good, and he should be given the chance to make more films. But aren’t his subject and the people he depicts just another mule, delivering us a fresh take on an old story? We go looking for stories to tell, and even the noble projects, once packaged, are just stories in the end. I don’t know if it would help, and perhaps even fewer people would care to see it, but I think we should consider some new packaging. Dickens won’t know the difference.