Seeing Is Believing

by Chris Wisniewski

Standard Operating Procedure

Dir. Errol Morris, U.S., Sony Pictures Classics

Often when it comes to Errol Morris, the more you see, the less you know. Some documentarians aim to answer and resolve, but Morris is almost too content to leave us adrift in ambiguity, regardless of the political, moral, and epistemological repercussions. After a New York Film Festival screening of his last film, the Oscar-winning The Fog of War, the woman seated next to me was angry—violently, vocally angry—at what she perceived to be the film's sympathetic treatment of Robert McNamara (or should I say, its failure to unequivocally indict him?). I wondered then: why the vitriol? Was it because she disagreed with the film, or because it challenged something she had previously thought she knew to be true? Uncertainty can be an upsetting thing.

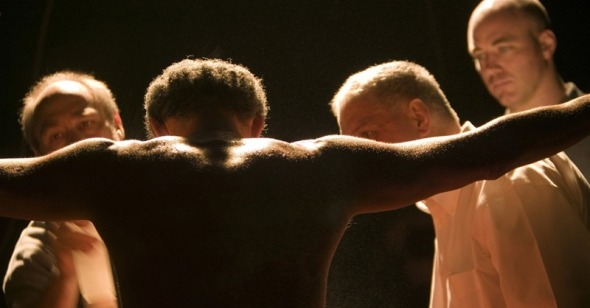

Morris's new film, Standard Operating Procedure, opens with a photograph of a sunset. Many photographs follow—of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib humiliated, abused, and dead. What could be more certain, more concrete, than a photograph? In Standard Operating Procedure, Morris relentlessly presents photograph after photograph, some of them graphic—a few pornographic—most of them nauseating. I am not sure, ethically, how I feel about Morris displaying these photographs of people humiliated and tortured for our edification, and I can certainly admit this was the least pleasant filmgoing experience I have had in some time, yet the movie feels vital. These images are undeniable and irrefutable; they exist, ontologically, as evidence of a wrongdoing (somewhere, a precocious undergraduate will write an A paper on André Bazin using this film as a case study). “That’s why I take the pictures,” explains Specialist Sabrina Harman, one of the chief inadvertent documenters of the atrocities of Abu Ghraib, “to prove the story I tell people.” But as the photographs of Abu Ghraib accumulate in Morris's film, there is an inevitable move from evidence to narrative—once we are confronted with the event, we must make sense of it and contextualize it. At one point, in fact, an investigator puts the photographs on a timeline, and as he arranges this photographic evidence “in time,” he seems to be doing the same thing a documentarian (and his audience) would do—to move from the footage (the documentation) to a chronology, a story, and, finally, an understanding.

Standard Operating Procedure is a twisted investigative documentary that purposely doesn't add up. Morris interviews the “bad apples” who perpetrated the disgraceful acts of Abu Ghraib; he shows the photographic evidence of their misdeeds; Sabrina's letters to her partner, written at the time, are read aloud as Morris's camera scans the text; investigators describe their investigations; lurid recreations of the atrocities play out as Danny Elfman's score obtrudes on the proceedings. But the power of the film rests not in Morris’s ability to create a coherent idea of Abu Ghraib through these disparate elements but rather in his ability to render such a master narrative impossible. Sabrina's letters are tortured, guilt-ridden, and sad. So how do we make sense of her smiles and thumbs-up to the camera in picture after picture? In her interview, Sabrina insists that she simply can't resist posing for the camera—but really, thumbs up next to a dead, decomposing body, just because you need something to do with your hands? Meanwhile, Lynndie England defends herself valiantly throughout her interview, but she still lets out a damning chuckle after recalling how one prisoner was made to masturbate at length in front of her. What—or whom—can we trust in this movie, besides the photographs themselves?

Morris has already drawn criticism for the overt aestheticization of his reenactments; such complaints don't so much miss the point as see the point, identify it, and then misinterpret it. Standard Operating Procedure sets up competing levels of discourse—the photograph, the letter, the interview, the reenactment—and then explodes them, rendering Abu Ghraib itself incomprehensible. Still, it's the need to make sense of Abu Ghraib that drives the film. We must somehow try to understand these events, which seem to stand in direct opposition to our self-image as a nation and our idea of our military. It is not enough to look at a photograph and admit what happened. By tracking and retracking the what, Morris leaves us contending with those most troubling questions: How and why? Uncertainty can be an upsetting thing.