Safety First

By Travis Mackenzie Hoover

Half Nelson

Dir. Ryan Fleck, U.S., ThinkFILM

I must profess a slight bewilderment at the widespread critical praise Half Nelson is currently enjoying. To hear these scribes talk—and not just the fluff critics but responsible writers as well—it represents something new, bold, and challenging. In reality, Half Nelson is the same old Indiewood drama with some extra surface noise both narrative and visual: while changing one’s perception of the old teacher-student mentor relationship and the problems of a crusading educator in his mission, it’s still just a bit of low-stakes liberal hand-wringing. Though there’s a minor amount of creativity in the visual style and a reassignment of how the players in this tired narrative can act, the characters are just as circumscribed in their movements as in any other film in the genre.

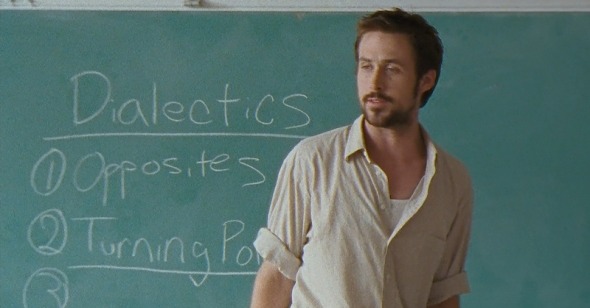

I’m informed that the relationship between white teacher and black student is complicated by the fact that the history teacher—ever so confused Dan Dunne (Ryan Gosling)—is addicted to crack and completely thrown by the job he’s assigned. This, allegedly, turns the balance of the relationship on its head: teacher is the one in need of guidance, and the student is likely to fill that particular void. Dunne also likes to tear off the shackles of conformity by tossing out the curriculum and teaching Hegelian dialectics, which, however badly he fails at the task, makes him an endearing figure to any educated audience member who chafed at the public-school mandate. He’s well-meaning but lost, intelligent but stymied by the enormity of his redemptive task—and as such he has managed to pull the wool over many a critic’s eyes.

While the Dunne character’s habits have been slightly tweaked, the nature of his mission has not. He’s assigned to clean up Dodge (or rather, he’s assigned himself the job), and he’s going to do it through the salvation of Drey (Shareeka Epps), the black student who discovers him freebasing in a locker room stall. While this might be seen as table-turning by some, it soon degenerates into the classic savior/saved relationship when it’s revealed that Drey is about to fall into the drug life. The dealer in question is Frank (Anthony Mackie), who is also designed to bust stereotypes wide open by being apparently kindly and not exactly “street,” but again it’s all window dressing when Dunne shows up to try and dissuade the man from ensnaring his young charge. That our hero doesn’t notice his compromised status only intensifies his martyrdom.

And Dunne’s martyrdom is really the name of the game. The genuine sensibility of Drey goes almost completely uncommented upon: beyond her no-bullshit demeanor and vacillation on the subject of whether she’ll deal, her character is ridiculously thin. Most of the movie belongs to Ryan Gosling and his issues: that’s him fending off the school curriculum, dealing with the return of an ex-girlfriend, romancing a fellow teacher, or feeling hedged in at a visit with his predictably oblivious family. We know so much about what drives his world because the filmmakers identify with him, warts and all; Drey is simply the medium for his good intentions, which of course redeem him from the hypocrisy of feeding the industry that preys on his student.

As befits its hero, the film’s style is meandering and ineffectual. The statement that an indie movie has a “documentary” quality is by now an eye-roller: Half Nelson is shot in jittery takes, features the odd jump cut and generally hangs around as it watches Gosling throw himself into his role. To be sure, the approach here is a tad more committed, based in some kind of quasi-Method attempt to capture the nuances of behavior rather than imposing some kind of smothering order. But order is what this movie genuinely needs. The film’s play at no-interference leaves a blank that has to be filled, and the lack of an opinion—visual, structural, narrative—means we have no guidance on what to do with the film’s events. We’re just supposed to take it as the proverbial slice of life, and not ask questions about why things are arranged the way they are. The style hides more than it reveals.

The filmmakers’ leftist bluff is called by the fact that it can’t imagine action that goes beyond one man magnanimously intervening on behalf of another individual. There’s no notion of collectivity, or just plain grassroots action, as that would dilute the spectacle of Dunne’s good intentions and perhaps make him more effectual than the self-pitying character (and filmmakers) would perhaps like. Take away Dunne’s individual efforts and one is denied a point of identification—and that point of identification is all the movie really wants. Half Nelson is about getting points for trying rather than figuring out a solution; instead of finding strength in numbers it wallows in the weakness of solitude.