Paris Belongs to Us

by Michael Joshua Rowin

The Complete Jacques Rivette

Museum of the Moving Image

Queens, New York

November 10 â December 31, 2006

Paris Belongs to Us would make a terrific title for a study on the French New Wave in summarizing that movementâs cultural and artistic ascendancy in the late Fifties and early Sixties if it werenât for two slight problems: its claim of a generational coup, and thus any romantic illusions of creative triumph, is directly contradicted in the film to which it belongs by the opening epigraph, âParis belongs to no one,â credited to Charles Peguy; and, even with the clarity of hindsight and historical perspective, Rivetteâs film is a well-intentioned failure. While 1959/1960 saw Truffaut, Godard, and Resnais each unleash epochal debut features that redefined the parameters of cinema and heralded the arrival of an era of fearlessly adventurous filmmaking, Rivette labored and labored as the second ever full-length New Wave film put into production ran into myriad delays and revisions, eventually released nearly three years after its conception having just missed the chance to sound the New Wave call to arms and emerging far too muddled to do so even if it could. Not that this was necessarily Rivetteâs goal. The least screened or popularly recognized member among the Cahiers du Cinema critics that went on to become New Wave legends, Rivette and his films have earned a sort of cult status since those halcyon days; Paris Belongs to Us, a first major effort of insufficiently rendered ambition and baffling results, thus shows the promise of an arcane, wide-ranging career that would only later discover its fulfillment.

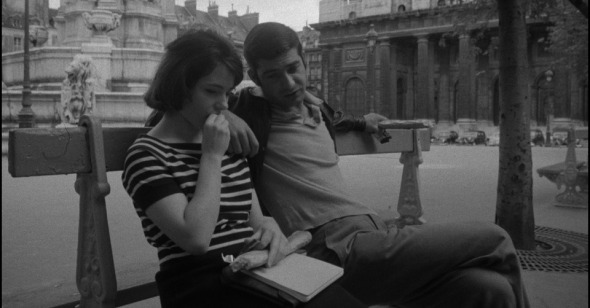

In Rivetteâs world circa 1957-60, Paris would belong to the new generation of the creative few if not for their paranoiac demons. Anne Goupil (Betty Schneider), a young literature student, falls in with her brother Pierreâs (François Maistre) Left Bank artist friends. One of those is Philip Kaufman (Daniel Crohem), a half-mad, half-bitter American Pulitzer Prizeâwinner staying in France to seek shelter from the McCarthy witch-hunts. At a party similar to the disaffected intelligentsia gatherings occurring contemporaneously in the films of Antonioni and Fellini, scenesters discuss the recent suicide of their bohemian musician friend Juan. Different theories about the death get tossed around, and Kaufman reacts violently. Only a day or so later Anne runs into Kaufman, who offers his own take: Juan was murdered as part of the plot of an ongoing worldwide conspiracy. The next to go, he states with certain conviction, will be Gerard (Giani Esposito), a theater director in this small but significant circle of friends struggling to put together a performance of Shakespeareâs Pericles. The common link between Gerard and Juan, beside their friendship, is Terry (Françoise PrĂ©vost), Gerardâs current girlfriend and perhaps Juanâs last one; a femme fatale, she is seen, in one of the few scenes not shown from Anneâs point of view, talking in secret and vague code with Kaufman.

Gerard has his eye on Anne, though, and recruits her for a part she is unsuited to play in Pericles. As sexual tension builds between the two Anne does some investigative work to track down the last recorded tape Juan made and which Gerard wishes he could use for his play. This leads Anne along many paths far enough afield of the main concerns as to elicit justified frustrationâif the first half of Paris stays on a steady, if often languid, course in coaxing the viewer with evocative clues and colorful incidents, the second half vanishes in a fog of dead ends and underwhelming revelations. Ironically, in contrast to the conventional arc of the conspiratorial thriller, as Anne questions more of Juanâs friends (including Godard, acting under the pseudonym Hans Lucas) and embroils herself in a possible underground political network, the allure of Kaufmanâs conspiracy erodes. This is in part due to the dialogue-heavy nature of Rivette and Jean Gruaultâs screenplay (their subsequent collaboration, the anomalous The Nun, was a significant improvement) and its often amateurish interpretation, but one could defend this fizzling energy by referring to the circumstances behind the film: Rivette created Paris Belongs to Us out of chaos, borrowing equipment, using leftover film stock, and asking for the spare time of his performers in order to fulfill his vision. David Thomson points out that Paris Belongs to Usâs âvicissitudes [are] subtly mirrored in the âstoryâ of the movieââincluding the constantly aborted stage production of Pericles that serves as a central metaphorâbut itâs a structural negative as much as an adherence to the New Waveâs guerilla-style, shoot-from-the-hip ethos. When Gerard asks Anne to give her opinion on Pericles, she states that itâs a disjointed work that makes sense on some other level of meaning. This is also Rivetteâs wink at the audience, no doubt, but one really longs for a definitive undercurrent to gather this mess into a coherent shape or else more poignant evocation.

I know, I know (altogether now): itâs not supposed to. Instead, the thinking goes, itâs enough that the major themes of Rivetteâs work exist here in an embryonic state: the collision between the life of theater and the theater of life, the real and imaginary conspiratorial forces that threaten the political left, the centerless, fragmentary void of modern existence. The allusions to Pirandello (Kaufman derides Anneâs participation in Pericles by attempting to show her that the lives of his fellow renters are more interesting than those of fictional characters, only to discover that a cast mate of Anneâs is one of them), Kafka (the endless labyrinth of The Castle), the Cold War (Juanâs music is referred to as âapocalypticâ), andâin a three-minute sequence lifted straight from the film itselfâMetropolis should theoretically concentrate the wayward storyline into something close to monumental and just beyond âpoetry.â Rivette expert Jonathan Rosenbaumâs lauding of Paris Belongs to Us rides on the filmâs role as a precursor to Rivetteâs own truly monumental Out 1 and Thomas Pynchonâs Gravityâs Rainbow in subverting and challenging the generic trappings of the conspiratorial thriller by offering ambiguity instead of resolution, the possibility of the characterâs solipsistic fanaticism in place of an explanation of the universeâs nefarious, seemingly uncoordinated designs. No doubt Rivette was onto something here, so much so that even as a director more likely to change styles and preoccupations than stay along the lines of auteurist constancy he would make a career exploring this macro-mystery. Perhaps then, writing âthe allure of conspiracy erodesâ as evidence of a lack of follow-through is akin to criticizing Pierrot le fou for having Belmondo talk to the camera. But Paris Belongs to Us falls in of itself for avoiding the possible rule that even a deconstructed conspiratorial thriller must be to some degree engagingâThe Castle is just as maddening and forever out of reach as Paris but pulls us in because of its author-surrogate protagonistâs unwavering obsession. Even with some scattered moments of genuine modernist dread and despair, Paris is too distracted and obfuscated to make the viewer care about its dismantling aims. Rivetteâs film takes on unnecessary sideshows when it should spring into a multidimensioned house of mirrors; it flattens into a dreary slog when remaining wishy-washy, as it does through most of its runtime, about abandoning its thriller cloak entirely.

To end at the beginning, then, comparing Paris Belongs to Us to New Wave debuts might seem unfair, but it ultimately vindicates its director. Those other films (and thatâs not including Cleo from 5 to 7 and Le Beau serge) immediately displayed their creatorâs talent in what turned out to beâto borrow a phraseâinstant classics, whereas Paris displayed Rivetteâs arguably richer potential (and definitely his greater difficulty) at the expense of solidified âquality.â Thatâs the way it is sometimes. Artists develop in their own way, at their own rhythm and by their own logic. Fortunately, though, if Pericles is to Paris Belongs to Us as Gerard is to Rivette, then at least Rivette went on to master his craftâat least we can see and evaluate this fascinating disappointment with its future payoffs excitedly in mind.