Pacing the Cage

By Nathan Kosub

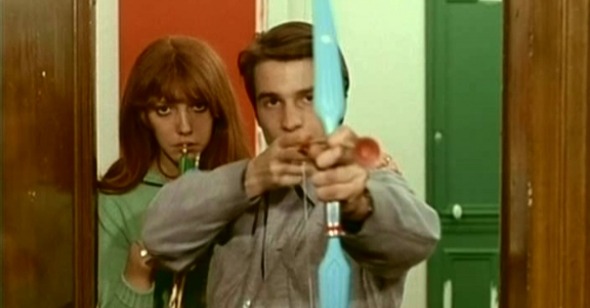

La Chinoise

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, France, 1966, Koch Lorber

For those of us who still think of Jean-Pierre Léaud as we first saw him, on library shelves in films directed by François Truffaut, La Chinoise is a gentle appeal. Without Jean-Luc Godard, would Olivier Assayas have still cast Léaud to drink from a comically oversized three-liter Coke bottle in Irma Vep? Would Tsai Ming-liang, his love for The 400 Blows intact, insist on Léaud’s large overcoat in What Time Is It There?, or on the physical gesture of a phone number passed on a piece of paper?

Léaud, with his easy exasperations, reacts. He asserts his nervousness instead of hiding it; his hands indicate an ongoing, unguarded surprise with his own disruptive emotions. Truffaut increasingly scaled the performances back, but Godard, like Luc Moullet with A Girl Is a Gun, egged Léaud on. With each new season, an old Godard film makes it back into circulation. La Chinoise should be ubiquitous. It anticipates not just the student riots in 1968 Paris but also the greatest in DVD supplements, the archived audition. Again, it was Truffaut who spliced Léaud’s tryout for The 400 Blows—an improvised question-and-answer—into the final cut. But where Truffaut courted naturalism through the unrehearsed scene, La Chinoise solicits the fleet-footed mechanics of invention. Léaud plays Guillaume, a student and Maoist, who pontificates at length, but only sometimes as Guillaume. Sometimes he is Jean-Pierre, sometimes he addresses his classmates, and sometimes he laughs at the crowd. If the audience is not us, it is Godard, who we hear, or maybe Raoul Coutard, the cameraman, who we see behind his camera.

Auditions are a way back to the real world. They blur actors and stars; watching them, we see just what caught the director’s eye, and then see it all around us. The world grows. Godard, it has been said, sees in cinema. Critics are right to call his gifts instinctive, but there is something natural in the artistic gaze that instinct can ignore. Instinct is regression to impulse and action. “Natural” is a quality of craft; grace is its gift, and grace is the line that divides Godard’s best films from the rest. La Chinoise, the chronicle of a group of student activists who engage in the communist upheavals of the era tangentially, and then in full, belongs unmistakably in the former category.

But La Chinoise is different from the others, which exult in the open air of Paris, in the liberties of traffic and daily life. La Chinoise is artificial, a set. Except for a brief montage at the end and a climactic ride in a train, the set is controlled. We are told of the artificiality—shown the clapboards for cues, the film stock, the cinematographer—but in feeling it is still very close to dancing in a Paris bar.

The inclination, perhaps, is to oversell La Chinoise, in the way that Godard’s previous film, Two or Three Things I Know About Her, was always oversold to me. That movie in particular, met with such heartfelt ovations upon its re-release, tempered so much of my curiosity for Godard. Godard found an aesthetic exhilaration in the transition from old Paris to new, in chaos and young faces. He was a wrecking ball with the lightest tools: color, hats, a jukebox. It is an early anomaly, a rare victory of impatience over control (not to be confused with complacency). Subsequently, Two or Three Things is a movie about parts of Paris that other directors have improved upon. In the Eighties, Eric Rohmer brought a real consideration to the suburbs, to Marne in Les nuits de la pleine lune, and Cergy in L’Ami de mon amie. Cergy and Marne were unlike the Latin Quarter streets where the Young Turks of the French New Wave watched movies. But Rohmer wrote characters who were not afraid to occupy these new landscapes—characters who embraced the man-made lake or apartment complex wholeheartedly and yet remained engaged with one another. In those films, Rohmer quieted the modern age as significantly as Playtime did. Once someone has done that—moved through the world and found the same people as before—old fears and apprehensions seem outdated.

Where Two or Three Things sounds alarms, La Chinoise lends an ear and eye. Anne Wiazemsky, the star of the film, married Godard. He liked to pick her up at the Sorbonne in his sports car. They saw movies together and talked politics. With La Chinoise and ever after, politics were paramount to the director; he looks old with his cigar at his typewriter in Histoire(s) du Cinema, haggard but not particularly tired. Still, any recap of the politics in La Chinoise would be, on my part, insincere. They are there, but obscured, deconstructed, thrown about like paint. Context is the hardest sell for political films—the cul-de-sac of appreciation. If La Chinoise prefaced student revolts that seemed outlandish upon its release a year prior, the film is free and clear today, not an artifact, still new.

In one scene, Léaud stands at a chalkboard where someone has written the names of famous writers. He takes a damp sponge—a heavy, oceanic thing—and erases the names one by one. In place of the names, he leaves water, applied thickly, like paint. The chalkboard becomes a palette, the sponge a paintbrush. The physical world is reimagined, even as Godard stays inside, away from sun.

In The New Republic last week, in a formal complaint against theoretical prerogatives, Jed Perl wrote that it is impossible to experience “an ordinary summer day” and not think of green as a primary color. Red is the color of La Chinoise, and if a summer day awakens us to the disparity between what we are told and what we see, Godard’s template—red book spines, red shutters, red lampshades and upholstery—is less a communist’s tone or commentary, and more a spendthrift’s stab at saturation: Technicolor on a budget. Instead of wasting Coutard on interior design, Godard frees a room from the parlance of efficiency and cost effectiveness.

He also separates himself from the cultural homogeny of the French New Wave by casting a black man as a guest lecturer on Maoist philosophy. It’s easy to believe, in movies like Breathless, that Paris in the Sixties was full of sailor-shirted bourgeois whites. How nice to see Godard begin to deconstruct his own worldview, or at least expand it beyond geopolitical outrage.

In fact, La Chinoise exemplifies Godard’s ability to make the image on the screen whatever he wants to see. Ever the contrarian, he is even elegant when he so chooses. On a long train ride, Wiazemsky debates insurrection with Francis Jeanson, a French intellectual who opposed the Algerian War. They sit in a dark green cabin, their voices soft and lovely to listen to. On the train, the dominating palette is countryside shades: grey sky, low slate rooftops, and spindled winter branches. France passes by like film through a projector, a comfort in contrast to what they say.

“Francis has the sense to know that an image isn’t anything but an image,” Godard said in a 1967 interview in Cahiers du Cinema. “All I ask people to do is listen.” Andrew Sarris, in a 1968 review for the Village Voice, made note of a character in the film eating bread with butter and jam while he talks about his defection from Wiazemsky’s Maoist cell. “Godard’s character,” Sarris wrote, “would rather eat than talk.” Jeanson discourages action for action’s sake, but Wiazemsky, who hears him out, acts on her impulse to kill. If no one talks and no one listens, impulse is all there is. Eating and assassination spring from the same well. Impulse is Godard’s secret; it’s how he makes Jeanson look old. But Léaud looks young, Wiazemsky beautiful, and La Chinoise, thank God, not a day past essential.