Zen Palette:

An Interview with Christopher Doyle

by Vicente Rodriguez-Ortega

“I want to be the Mick Jagger of cinematography. I dance a little like Mick…for about five minutes max…and then the Keith Richards in me starts screaming for a drink or an out…” —Christopher Doyle

Surrounded by washed-out and dirty rows of tiles in a kitchen somewhere in Buenos Aires, Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung’s bodies caress the impossibility of their love, daydreaming through the sensual notes of a tango that the world around them has frozen, their years of struggles and noisy verbal outburst are over, finding each other at last. The camera stays still, mesmerized, paying tribute to two bodies that learn to find each other in the course of an eternal second that is bound to tragically fade away. As the tango keeps wrapping the intensity of their emotions, their mutual grip goes tighter and closer, their mouths collapse into each other. The tango ends, their dance is suddenly tinted with the reddish palette of the Buenos Aires street life. A canted angle announces Leung’s solitude once again, sitting in the steps of a bar, drinking and thinking his moment of joy, his instant of love has slipped away. No more Happy Together.

A twentysomething woman moves frantically around a shoddy apartment somewhere in Hong Kong. She cleans up the dust, fills the fridge with beer, sets up a fax machine. We are in full-speed Hong Kong. Through the cracked glass of the window, we see a bullet train cruising by. The camera follows her, inspects her from top to bottom, handheld and lawless, maneuvering through every corner of the diminutive semi-private polyglot space of the apartment. As she exits the camera pulls back, makes a quick movement to the right, only to see another train passing by, carrying infinite souls, any one of which could be her. Fallen Angels swallowed by the labyrinth mosaic of Hong Kong’s cityscape.

Now, western Australia. Three little Aboriginal girls are taken away from their mothers, victims of the white men’s racial policy. A car blocks their way, a screaming soldier waves a paper in front of their faces. It’s the law. Now the three kids are locked in the car, their mothers lying on the yellowish earth, hardly able to bear the burden of their despair. A thousand-mile Rabbit-Proof Fence and the immensity of the Australian desert become a dark glass cage through which the three girls perceive the world that was theirs and is now left behind, trapped inside a bleak vortex of tears.

Such are the eyes and soul of Christopher Doyle: chameleonic, shifting, thick and excessive, like the multifarious textures of the infinite spectrum of images he composes. In his 25-year career, Doyle has worked with Edward Yang, Wong Kar-wai, Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou, Philip Noyce, and Barry Levinson, to name a few. His imprint is not necessarily distinctive but purely strategic. Rather than impose a deadpan recipe to his stories, he rejects the universal to capture the unbound space. His imagery triggers emotions, commands feelings, and then out of his high-contrast and saturated blues, drops calmness. He enables the unknown to unfold, expose itself, hide in the corner of a wide-angle distorted space, and then come back, dance before our eyes like a chanting canvas.

Doyle loathes prescriptions and embraces errors. He trusts his mistakes and makes them part of his impossible mise-en-scènes. Black and white do not exist, they creep into the story due to the unpredictable magic of film processing or defective film stock. He opens a crack in the image and throws himself into currents of unknown shapes and volumes, of a reality he doesn’t aspire to control but only to learn from. He offers to us wishes, yearnings, and fears, coloring our memories and catalyzing our imaginations.

On the occasion of the long-awaited American release of Zhang Yimou’s Hero and the presentation of Thai director Pen-ek Ratanaruang’s Last Life in the Universe in the 2004 Tribeca Film Festival (to be released stateside this August), Christopher Doyle visited New York City. Whereas Hero is a nonstop feast of audio-visual pyrotechnics, impossible choreographies of dancing sword masters and digitally saturated compositions, Last Life in the Universe is an edgy, acid, and provocative black comedy that allowed Doyle complete creative freedom and outright experimentation. On his way to present a photo exhibit in Seattle, Christopher Doyle shared a few words with Reverse Shot.

Reverse Shot: You recently said that when a filmmaker gets you, they get the complete package. You are not only involved in the cinematography but also in the re-writing of the story as you shoot.

Christopher Doyle: For better of worse, they do get the complete package. Although I’ve known Zhang Yimou for a long time, I got involved in Hero because of the producer Billy Kong. Originally I was supposed to shoot Crouching Tiger for him but I couldn’t since I was shooting In the Mood for Love and it kept going on forever. Zhang Yimou and I come from a very different culture, different filmmaking culture too. Lots of people seem to think filmmakers are similar and overlook this. Filmmakers might have similar intentions but the way they work is informed by their culture. The way the industry works in America is because Americans are like that, same in France. I’ve worked in China many times but it implies a different kind of engagement. It’s more formal. In Last Life in the Universe, because of the fact that Thai culture has a much more loose way of approaching things, it was an open collaboration. It’s another structure. This comes from the size of the films, character of people involved. For me, actually, on a very personal level I prefer working on films like Last Life in the Universe. I think you can see that, if you really look at it, you can see the person behind the film and you can see their pleasure. There’s not much else there! It’s a small story. Hero is a much more formal film, it’s a very structured film and the way it was executed is much more structured as well. As a filmmaker you have to try different areas and different places.

RS: Would you compare making Hero to Ashes of Time? Since the latter is also a martial arts film set in the desert, how did your experience in the former help you to work through the challenges of the latter?

Doyle: Yeah, I could not have made Hero without Ashes of Time. The desert really informs you. I’ve made five desert films. The desert has been one of the important learning platforms. It’s a place that has taught me a great deal about filmmaking because you can’t light the desert. You exchange, it’s temperamental, it’s like some relationships. It’s vast and beautiful and engaging. And yet there are a lot of details in the desert. It’s all there. The desert taught me to look more. To be more observant, more patient and to do less. Don’t intrude. Take what you have and make it what you need. The city of Hong Kong also taught me that. In Hong Kong the space is so limited and people move so fast and there’s certain kind of energy and all those things are reflected in Hong Kong–style filmmaking.

RS: What was the process of composing the mise-en-scène in Hero? You have these huge spaces and also this extremely complex choreography. In addition, there’s a wide spectrum of colors that define the narrative structure of the film.

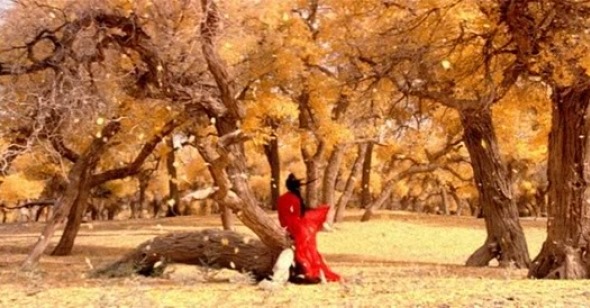

Doyle: Zhang Yimou is a cinematographer; he has a certain visual energy. I’ve done many films where we have avoided red and that was a very conscious choice; up to In the Mood for Love, there’s no red in Wong Kar-wai’s films. For Chinese, red has a very special significance. It means joy. It’s the color for marriages, temples…in many ways it’s the most beautiful color…and it’s a very auspicious color, with many associations in Chinese culture. That’s why we have avoided in the past. In Hero, we wanted all these cultural associations. The point of departure is color. You have a Rashomon kind of story. And then color. The easy one was red, red as passion. We were not sure about the others and that was the journey, specifically based on locations. Sixty percent of the film is shot outdoors, and, for example, you cannot change the color of the lake. We knew the lake and the forest with the yellow leaves were very important. So we searched for the locations and from them we reworked the script, instead of imposing a color to a particular location. I think this also comes across in Last Life in the Universe. The house is very much a character in the film. When we found that house I insisted on it, because it had such a presence that I felt the film would be three times better. In Hero, we were choosing colors depending on the locations. The most difficult one was the flashback, in the Emperor’s palace, when they almost assassinate the Emperor. We basically ran out of colors and we were not going to use pink! Green was the choice, it was the only color we felt comfortable with. I knew Fuji has an interesting green so we went along with it.

[Vittorio] Storaro claims green is the color of knowledge. It’s not as simple as Storaro and other people claim. It’s not a theoretical exercise; it’s a practical one. To say the stuff that Storaro says to the kids is really misinformation. It’s dangerous, it confuses people, and makes them think that film is a theoretical exercise. As a cinematographer you’re dealing every minute with weather, people’s emotions, technical problems. The style comes from the contingencies of the film and that’s very important to realize for younger filmmmakers.

RS: Like the black-and-white shots in Fallen Angels. They were the result of a problem…

Doyle: We fucked up with the film stock. It was old. We couldn’t re-shoot…so of course it was foggy in color. We said: “maybe this can represent something so let’s pick some other pieces,” and that’s what we did. Because of a mistake, a certain structure came out of the film and you can write a PhD about it if you want. What happened was that we gave it a system, so we made the most important parts of each scene in black-and-white. But that was a solution to the problem, not an original concept. We just appropriated the mistake and made it work. It’s a more intuitive, open, or, maybe, Asian way of working.

RS: Fallen Angels was completely groundbreaking. It’s a film in which the closer you get to the image the less you see. This is obviously very different from Hero, in which everything is supposed to be pristine and harmonic…

Doyle: Hong Kong and the desert are two very different spaces. Both films are totally informed by the location where they happen. In addition, Wong Kar-wai and Zhang Yimou are two very different filmmakers in their approach to the image and storytelling. Hero, above all, is a celebration of martial arts chivalry.

RS: Is it true that Tony Leung’s apartment in Chungking Express is your actual apartment?

Doyle: I still live there… it’s actually a Japanese tourist stop. Especially after the movie came out in 1995. They would take photographs of my house all day. It’s right in the middle of Hong Kong. As a result of this, everybody knows where I live. Just ask in the street. Downstairs, there are lots of bars. They all know me because I’m always in the bar.

RS: I’d like to talk about Gus Van Sant’s Psycho remake, on which you worked. Would you agree that contemporary cinema is, to a great extent, defined by an appropriation of other cinematic traditions, genres, visual styles? Wong Kar-wai once said that current filmmakers no longer make original works of art, they recycle what has been done before.

Doyle: No. I think the only time I see films is on planes. I take a lot of planes, so I do manage to see lots of films. But to me film is not the basis of my life, my creative energy comes from other things, usually music, or people, or the way in which I live. The people who decide to work with me know that. Therefore, what you mention is their job. Gus Van Sant knew that. Psycho is not a film but a conceptual artwork. I don’t think you need to see the film. It’s just a concept, a very expensive one. It cost $20 million to make and $40 million to promote. If you went to Hollywood, and tell them let’s do some performance art, they wouldn’t give you $60 million. They did in this case. My role in Psycho was not to know, not to remember the original film.

Same with martial arts films. Because of where I live (Hong Kong), the people I’ve worked with, I know the working details. In fact, I know better than Zhang Yimou the actual physical procedure to make a martial arts film. However, it’s much more his job to try to make his own film. That was a difficult thing for me to work with because Zhang didn’t know the procedure to shoot a martial arts film. Now, the West is taking over, The Matrix and all that…they are borrowing this style but they’re structuring scenes much more systematically…storyboards, all kinds of preparation.

However, Hero was shot like an old-style Hong-Kong martial arts film. To be honest, you don’t know what you are going to get while shooting. The martial artists don’t know either, but they make it up as they go along and they continuously try new things. It’s choreography. Which means the communication is quite difficult and the logistics are quite complicated as well. Basically, what you need to do is to try to direct the film in a certain direction and then take what you need. You’re dealing with very special people. Martial artists come from a very proud tradition and you know, they can beat the shit out of you…

RS: So in Hero, Zhang, the choreographer, and the martial artists planned a scene and then you adapted to what they were doing…

Doyle: Zhang Yimou tried but it’s much less planned than other forms of cinema. The wind is too strong so someone cannot fly, or, on the lake, it’s very difficult to get people in the air, you need wires…it’s a very slow procedure. Sometimes, you get two or three shots in a day. It takes a lot of concentration and collaboration. Even if you have a plan, then you have actors that are tired, or we are in a very high altitude, most of film is at 3000 thousand feet, physically it’s quite difficult to do. So it’s not a Tarantino kind of exercise, it’s much more organic. Zhang’s main reason to make a martial arts film is political. If you make a genre piece, you have much more scope than if you make a film about people taking ecstasy in Beijing. It’s much easier to get things across. There’s still censorship, and script supervision in China.

RS: The ultimate message of Hero seems to defend a kind of internal imperialism. It has been widely criticized as racist. What’s at stake in this film?

Doyle: There’s a really strong reaction for people who know Chinese history, especially in some areas in China and Taiwan. It’s a little bit revisionist for some people in terms of the white-washing of this historical character. There are many films about this period, like Emperor and the Assassin, so the jury is still out. There’s a debate about what this emperor really did. He was the first emperor of China; he did unite the country. How did he do it? He was an extremely ruthless man. Zhang’s intentions and personal relationship with the politics of his country are much more complex than that. I don’t know and I don’t think I have the right to talk about it. I don’t choose films based on the script but based on the person. If it was too disgusting, I’d stay away from it.

RS: After seeing To Live and Red Sorghum, which are very critical films, it’s surprising that Hero…

Doyle: You’re saying he sold out, right? I can’t judge, but many people say that…I can’t judge. By the way, Zhang is a very rich man…I have very rich friends in China and I’m not really sure…I’ve seen the way society is evolving now…it’s going in a direction I don’t personally like…but look what they come from…look at the shit they’ve been through…At a personal level, I can reject certain aspects the way China is changing. But I don’t think I have any right to criticize them because they’ve gone through a hell I don’t truly know, I don’t have any right, or precision, to be critical. Zhang has to evolve the way he wants, that’s his choice.

RS: In Hero, calligraphy is represented as an artistic process, having an organic relationship with the individual psyche and also his abilities as martial artist. In the end, this same calligraphy is used in order to offer the unity of China, “Our Land,” as an ideal and to endorse the Emperor’s slaughtering practice.

Doyle: In Chinese it’s slightly different. The ideogram Tony Leung writes, on the one hand, means “Under Heaven”; it means there is a god. It also means “Under the Emperor.” Of course, it still has this implication that this is our place, also that it’s a gift, given to us by Heaven, it’s a unified place but it’s a gift. It’s not quite as heavy as “our land.” You have to take into account that China means “Central Country.” Chinese people have a very centralist worldview.

RS: In the trailer of Hero, the film is introduced as “Quentin Tarantino presents…”

Doyle: Oh really?

RS: According to what I’ve heard, Miramax was hesitant to release the film and Tarantino volunteered to make it happen. Though his intentions might be good, Hero is being sold to audiences as a Tarantino product with Jet Li created by the producer of Crouching Tiger.

Doyle: To me it implies that they want to trick everybody into seeing a martial arts film and make all the money in the first weekend and then they don’t give a shit. Hero is not a martial arts film as Crouching Tiger is. If you go to the film, expecting back-to-back action, you’re going be disappointed. Crouching Tiger, because of who Ang Lee is, has a more American background. This doesn’t have a user-friendly American narrative structure. It’s much more literary. I think it’s the wrong angle to promote the film.

RS: How would you compare the work of Zhang and Wong Kar-wai to that of Tarantino, who is a great appropriator, combining different film styles and traditions?

Doyle: He’s like that in person too…He never stops talking. Quentin is quite fun in a bar…. I think that, in a positive way, he references enough stuff so people go to see the other films. Tarantino promotes a certain vision of cinema that is different. However, I do think his intentions are good. Personally and most of the people I’ve worked with, we come from a different place. Whatever you’re appropriating, you’re absorbing it, it’s filtered through your unconscious and it comes back as something else. Wong and I reference multiple things, but we’re not repeating them. The opposite, we usually avoid repetition. It’s impossible not to repeat other things. Nothing is original, but it can be very personal and the angle, the intention can be very personal.