Those of us who survived the year 2017 with our minds and bodies mostly intact might not have much to show for it, cinematically speaking. Throughout the last 12 months, it often seemed like there wouldn’t be enough quality movies to fill out our annual top ten at all. But the usual amount of festival holdovers and winter debuts helped bring our poll to a mildly rousing conclusion. Ultimately, there was enough passion to go around to make the film in our number one slot a surprising landslide selection, sitting very comfortably in the lead—in fact the title of that film defines its unexpected come-from-behind placement. Otherwise on the list, we have some films you may have heard about: a frank and complex gay love story, an exciting breakthrough from an important new female filmmaker, a fleet drama about young people in over their heads committing violence, an exhilarating story about the precariousness of childhood performed by a vital cast of young newcomers, a brilliantly conceived tale from a cinematic whiz-kid taking place in three discrete space-times. But no, we’re not talking about Call Me by Your Name, Lady Bird, Good Time, The Florida Project, or Dunkirk—top picks in most other polls, and which didn’t quite crack our list. We’re glad to point you toward some films that thrilled us, often because they existed outside of trends and consensus.

As always, our films were determined by soliciting top tens from our frequent contributors from the past year. Each writer’s top-ranked film received ten points, their second getting nine points, and so on.

[Capsules below written by Julien Allen, Ashley Clark, Matt Connolly, Michael Koresky, Chloe Lizotte, Nick Pinkerton, Emma Piper-Burket, Jeff Reichert, Imogen Sara Smith, and Chris Wisniewski.]

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Though they are separated by over a century, as well as an ocean, their gender, and their principal artistic medium, Emily Dickinson and Terence Davies, the British filmmaker who reimagines the American poet’s life so brilliantly in A Quiet Passion, have much in common. Both have suffered from being woefully underappreciated by their contemporaries, and both have deep attachments to family, soul-stirring conflicts regarding religion, and deep skepticism, bordering on hostility, towards the mundane trappings of their social environments. Perhaps this explains how Davies manages to create such a sympathetic and human portrait in his elliptical and intimate biopic. As embodied with wit, intelligence, and vulnerability by the astonishing Cynthia Nixon, A Quiet Passion’s Emily is neither a dreary recluse nor simply a tortured artist. She steals late nights to write her poems; hurts at bad reviews; weeps for dying parents; flirts with a married pastor; rages at an unfaithful brother; dotes on a beloved sister; and scolds her family’s servants, then begs their forgiveness—all with the strident self-confidence and thinly concealed vulnerability of a genius made of flesh and blood.

Davies’s film owes much to Nixon’s performance, and to Dickinson’s poetry, read quite beautifully by Nixon in recurring voiceover. For the glorious filmmaking, though, he can surely take credit. There are breathtaking shots and sequences throughout—working, as the movie wears on, in an increasingly confined setting, he uses cast shadows and intrusions of sunlight through windows to define the home that becomes Emily’s refuge and prison—but his coup de cinema may come early on: no single shot I saw this year floored me quite as much as the languorous 360-degree pan around the family’s parlor that brings them each, for a moment, into close-up. With A Quiet Passion, one of our greatest living directors has turned in his finest work since 2000’s The House of Mirth. Davies’s film has generated only modest attention in the year-end roundups that have proliferated over the last several weeks. It’s no matter. If Dickinson’s legacy teaches us anything, it’s that genius endures far longer than any artistic fad. In the best possible ways, A Quiet Passion is a film worthy of both its maker and its subject. —CW

2. The Human Surge

In recent years, many films have frustrated obvious classification by consciously and deliberately blending established modes of making. More fascinating, though, has been the emergence of shape-shifting works like Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge or (see below) By the Time It Gets Dark, which seem blissfully unconcerned with arguments over form, allowing themselves to do whatever, whenever they please. Thus Williams, in his debut, is able to string together a movie from gangly, roving handheld shots that move viewers seamlessly from Buenos Aires to Mozambique, then down into an anthill and out the other end to land in a Filipino village on the opposite side of the world. The Human Surge feels at times like observational nonfiction, yet doubles back to certain contemporary questions with such regularity that one can sense an underlying, constructed design. These questions—of youth and work, sexual capital, and the myriad varieties of screens and devices we use to keep a handle on or express all of these things—are so enmeshed in his scenarios of underemployed youths that it’s some time into the film before it becomes clear what Williams is pursuing. The film’s circulating concerns, along with Williams’s unobtrusive, nearly ambient approach to filmmaking, conjure a hazy, oneiric spell that recalls Apichatpong, perhaps the most peerless exemplar of bounds-free filmmaking we have, without ever feeling anything less than its own beast. The Human Surge is a film that casts a critical eye on our moment—characters across scenarios are in constant search of connectivity or places to plug in their devices—that’s too artfully done to devolve into a broadside. It’s the most laid-back movie of grand ambition to come along in some time. —JR

3. Personal Shopper

Supernaturalism, art history, technology, and life on the peripheries of celebrity culture intersect in director Olivier Assayas’s second collaboration with Kristen Stewart after Clouds of Sils Maria. Personal Shopper is posited as a thriller, yet the dramatic plot turns become mere side notes to the internal journey of its disaffected young protagonist, Maureen, a role written for and superbly brought to life by Stewart. In her own words, Maureen is in Paris “waiting”: on the surface, she's waiting for a sign from her twin brother, who died there months earlier from a heart abnormality that she also has, but in a deeper sense Maureen is waiting for her own future to reveal itself, perhaps to find out if she has one at all. The rhythm of the film fully embraces this state of suspension, so that when real drama or trauma occurs (and it does), it is quickly subsumed back into the stasis of Maureen's daily routine as a high-end personal shopper for a spoiled A-lister. The constellation of detailed moments creates the suspense and mystery of the film: Maureen experiences the presence of a ghost in her brother's house, later she hears an offhand comment about technology being a conduit for the spirit world, so when she receives a knowing text message from an unknown number it feels entirely plausible for her to reply, "Are you alive or dead?" Nothing is overplayed here, instead each development evenly unfolds, building upon what came before. The film itself is a timely study of the tension that exists between the tedious minutiae of tasks at hand and the deeper existential questions beneath it all. —EPB

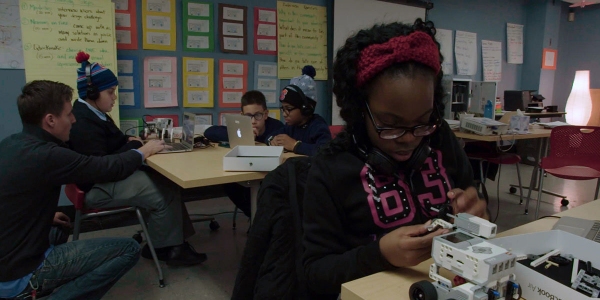

4. Ex Libris: The New York Public Library

Frederick Wiseman has for 50 years made films that, through the exhaustive survey of individual institutions, document the world as it is. This makes him invaluable as an American chronicler. Within those deceptively matter-of-fact, encyclopedically in-depth chronicles, however, one can catch glimpses of the world as it might be, or as it ought to be—individual human potential as it struggles and strives for expression within the cosseting framework of institutions, flawed as any human endeavor must inevitably be. This makes him invaluable as an American poet. Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, though deceptively dry in method, is an exalting work of cinema, profoundly respectful of the intelligence of its subjects and in thrall to the power and pleasure of ideas—a highlight is a reading of the “Declaration of Independence” through a sign-language interpreter, which gives that document a renewed, resounding ring. A work of serene mastery, which not only leaves one resolved to do and be better, but certain that such a resolution is possible. Excelsior! —NP

5. BPM (Beats Per Minute)

The characters in BPM (Beats Per Minute) are facing death, so they are frightened. But the film itself is frightened of nothing. Rambunctious and impious, laughing at death and crying at life, BPM is a war film, in which the enemy is ignorance. Drawn from soft-spoken director Robin Campillo’s former life as a blood-bag-wielding activist for the 1980s Parisian AIDS-awareness pressure group ACT UP, this Cannes prize-winner ignited the French box-office despite making not a single concession to mainstream sensibilities. In this war, strategic plans are laid; offensives—against public authorities and AIDS drug companies—debated in open forum by allied forces (homosexuals and hemophiliacs of every stripe and creed) to rid France of its indolence and shame. Within this dirty Utopia, Campillo alights on a smaller struggle: that of neophyte activist Nathan (Arnaud Valois) and the dying Sean (phenomenal Argentine actor Nahuel Pérez Biscayart) to find a common thread amid the conflict, to love and die with dignity. The clock is ticking for all its players, but their sacrifice in the cause of a better world is perfected in BPM’s greatest aesthetic pledge: like the Sibyl’s prediction in The Aeneid, Campillo’s own Tiber—the Seine—runs red with blood. —JA

6. Phantom Thread

At his best, Paul Thomas Anderson specializes in structural ambiguities—but unlike other artists he never lets these ambiguities collapse his narratives into ciphers; instead his films offer precarious energies that suggest new interpretive directions. With Inherent Vice, this elusive quality became a neo-noir device, its possibly dreamed logic dissolving into a bad trip through an irrational late sixties by way of Pynchon. Phantom Thread sees Anderson confront this tension in both form and meaning: he turns a Gothic romance into an investigation of a human need for mystery; of how there might be a fueling nourishment in superstition, even if we’re aware of its artifice. With a precise blend of comedy and light surrealism, it refracts Du Maurier’s Rebecca into the story of a spouse and sister’s management of a fragile male ego; Vicky Krieps and Lesley Manville anchor the film in beguiling, nuanced depths. Just as Daniel Day-Lewis’s character sews hidden messages into garment linings, Anderson implies dormant secrets through his mesmerizing slow zooms—a worthy heir to recurring dreams of Manderley. —CL

7. Nocturama

A chic and shocking shadow play on contemporary terrorism as an abstract tangle of intent and effect, Bertrand Bonello’s controversial Nocturama finally emerged in U.S. theaters in August almost a year after its 2016 Toronto premiere. Bonello grants only mere flashes of motivation—a snatch of Marxist chatter at college here, a glimpse of economic disaffection there—for the incendiary activity (a series of bomb explosions across Paris) that is meticulously planned, then executed, by his gloomily gorgeous young cast of characters in the film’s mercilessly suspenseful first half. This metronomic segment thrums with a scurrying, ferrety energy, and makes terrific use of both Bonello’s expressive electronic score, and roving tracking shots indebted to the work of late British maverick Alan Clarke. (Before shooting, Bonello hosted a screening of Clarke’s 1989 Steadicam masterpiece Elephant for his cast and crew.) If there is scant space for the viewer to breathe in part one, there’s almost too much in part two: a lengthy, baroquely conceived set-piece in which the perps hide out at night in a cavernous, empty, high-end shopping mall, hopelessly and increasingly enraptured by its shimmering totems of consumerism. So much for the revolution. One can see why Nocturama was accused by some critics of trafficking in dilettantish provocation—by conventional standards of exposition and characterization, it is deliberately opaque and packed full of hyper-stylized, self-aware flourishes. Yet such charges are rendered moot by Bonello’s incisive, non-didactic observance of the myriad, often unspoken ways that class, sex, race, and gender inform the group's dynamics; and by the sheer emotional force of the conclusion, in which state-sanctioned violence rears its brutally ugly head, forcing the viewer to confront anew questions of entrenched societal power structures and the placement of our own sympathies. In an era where artworks are increasingly expected to exhibit unambiguous—if not utterly righteous—moral clarity, genuinely thorny and unsettling cinema like Nocturama must be encouraged. —AC

8. Wonderstruck

Like a cabinet of wonders, its central motif, Todd Haynes’s Wonderstruck is overstuffed with marvels, meticulously arranged with an unabashed determination to enchant. Brian Selznick adapted his own novel, which alternates between two parallel stories of runaway children set fifty years apart, plots that eventually fit together like an intricate puzzle. The 1927 story of Rose, a spunky deaf girl who loves silent movies, is cleverly shot in black-and-white without sound. No less loving is the recreation of Manhattan in the glorious squalor of 1977, rich with Kodachrome golds, jostling crowds, and festering garbage, where a motherless boy, struck deaf in a freak accident, arrives alone to hunt for the father he never knew. With its emotional heart nested in the dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History and the Queens Museum’s miniature panorama of New York, the story uncovers not only the sense of wonder but also the loneliness and ache of loss that underlie the curator’s—and filmmaker’s—desire to collect, preserve, and re-create. —ISS

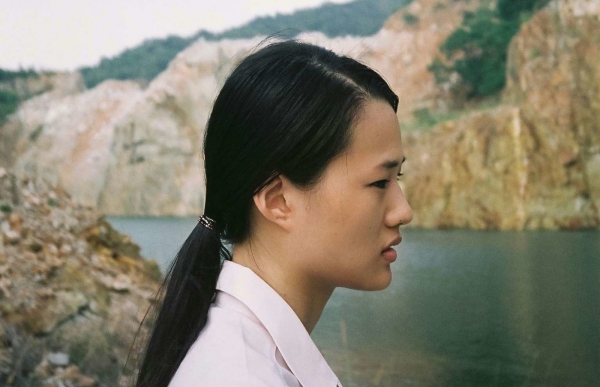

9. By the Time It Gets Dark

Many of the terms that can readily be deployed by critics to help describe Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong’s By the Time It Gets Dark—“cinematic memory,” “historical representation,” “hybrid forms”—are likely to scare most viewers away from a remarkably singular experience that is category-defying in the best, least aggressive manner imaginable. Suwichakornpong’s second feature finds her embedding a narrative of contemporary political disillusionment within a larger, gently metacinematic superstructure that allows for varying types of visual expression and narrative invention. Broadly: a young filmmaker is writing and directing a movie about the Thammasat University massacre, a horrific chapter in Thailand’s political history in which the government military attacked students protesting the country’s dictatorship—and which took place in 1976, the year Suwichakornpong was born. Yet her film grows increasingly internalized as it spirals out from this, incorporating multiple narratives and digressions, some of which one might expect to find (interview sessions with a middle-aged woman and former Thammasat student who insists “I’m not living history. I’m just a survivor”; clips from the eventual film within the film), others (a passage following the days and nights of a pop heartthrob; a consistent returning to a the shifting workaday routines of a young woman who always seems to have a new job) that serve not to fill out the central conceit as much as to create an overall sense of memory and perseverance as a free-floating, collective national reality. All are equally integral to the film’s structure and rhythm, and Suwichakornpong—clearly a true film artist—makes every shot in some way surprising or ravishing or both. Perhaps most gratifying is that she has made a completely undemonstrative work of shape-shifting ephemerality, which allows its characters to be introspective, self-aware people rather than pieces to be moved around a game board. —MK

10. Faces Places

Agnès Varda and JR’s unassumingly capacious documentary touches upon many ideas— creation, memory, legacy—but it’s perhaps most affecting as an ode to the vicissitudes of artistic collaboration. The delightful duo drive through the French countryside, photographing the largely working-class denizens they meet and plastering enormous versions of these portraits on the sides of local homes, farms, and public squares. That Varda and JR take the time to understand the quotidian rhythms of their subjects’ lives makes these monuments to the everyday all the more moving. With its exhilarating associative montage and quicksilver shifts of tone and subject, Faces Places is unquestionably of a piece with Varda’s legendary body of work. Still, the 89-year-old filmmaker’s odd-couple pairing with the 34-year-old photographer points to her continued investment in the joyful possibilities (and painful limitations) of working with another. Both are on display in Faces Places’ stirring closing scenes, with the callous absence of Varda’s storied cinematic colleague leading to the revelation of the film’s final face—an act of self-disclosure that Varda treats with the sensitivity of an artist and the tenderness of a friend. —MC