Moments of Truth:

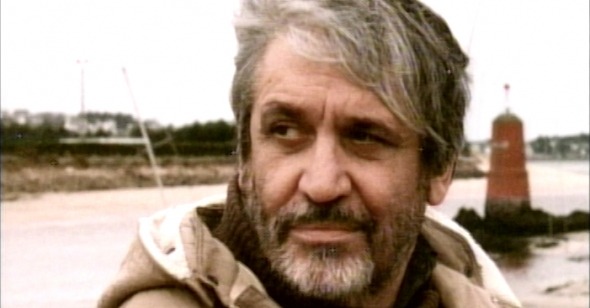

Maurice Pialat (1925–2003)

by Julien Allen

Museum of the Moving Image’s series Maurice Pialat, presented with support from Unifrance, the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, and Institut Français, ran from October 16–November 1, 2015.

“Realism isn’t what’s happening today, or what happened yesterday. When the camera rolls, there’s no present, there’s no past . . . there’s just the moment we’re rolling. You have to get as close as possible to the truth of that instant.” —Maurice Pialat

Near the end of Maurice Pialat’s most emblematic film, À nos amours (1983), there is a somewhat banal dinner table sequence, wherein a family is gathered to discuss, amongst other things, the merits of Picasso. The scene is then interrupted by the return of the family’s forbidding patriarch (played by Pialat himself), who was thought to be long gone from their lives—and from the narrative. This intervention is shot and edited, like the rest of the film, unremarkably, without musical or camera cues designed to mark the moment out in any way. To the audience, this is an incidence—albeit a low-key one—of narrative upheaval. To the confounded actors in the scene itself, it is something else entirely. None of them had been told that the Pialat character was going to return and their reactions are all real. The remainder of the sequence—unquestionably one of the most electrifying in the history of French cinema—is fully improvised, forged in a crucible of utter confusion. Pialat turns on his actors, offering insults and judgments on their characters, which are in some cases veiled references to the actors’ own lives and behaviors. He is like an ogre, come to consume the entire film in this moment. He asks his screen daughter (Sandrine Bonnaire) whose side she is taking. His screen wife (Evelyne Ker) strikes him. He throws her against the dinner table. No one emerges from a Pialat film unscathed. Least of all the audience.

A Life in Films

Pialat came to cinema late, like Robert Bresson, only shooting his first full-length feature Naked Childhood (L’enfance nue, 1968), after his 43rd birthday. He was born and raised (and would return to rest before his death) in a small village in the Auvergne, a verdant and unspoiled region in the center of France. In his youth he was an accomplished painter, but as with many of his peers and betters in the art world was unable to earn a living selling his work. Instead, he spent the 1950s in various sales jobs, for the likes of Olivetti computers and Volpi shampoo. In 1955, having abandoned painting as an artistic vocation, he tried his hand at writing plays and acting in the theater, a venture that briefly sparked, then fizzled out. Throughout this period Pialat owned a 16mm Bolex film camera and from time to time would shoot amateur shorts, some vividly experimental, others of the slapstick variety, but frequently emanating from scenarios of darkness or pain. He met Claude Berri in 1954 and they made ambitious plans, which were never fully realized, to collaborate on numerous film projects (Berri would write and act, Pialat would direct). In the end, Berri would become an Oscar-winning behemoth of French cinema (directing Jean de Florette and producing for Roman Polanski, Milos Forman, Bertrand Blier, and Jacques Demy), by which time he and Pialat had long since gone their separate ways.

This narrative of struggle and frustration—an experience of arguably greater value to Pialat’s work than any of his early artistic endeavors—would continue throughout Pialat’s career, even during his periods of success. His uncompromising (bordering on cruel) approach to his craft, his deliberate manufacturing of disorder and tension on film sets and his voracious personal craving for the love and respect of his collaborators would eventually lead to his falling out, at one time or another, with almost everyone he worked with—and with only one or two exceptions, irreparably so.

Pialat also spent most of the 1960s, the decade in which his filmmaking career gradually came to life, feeling isolated and mistreated in the wake of the noisy attention being paid to the French New Wave; he felt completely excluded from this movement and openly ridiculed it. For Pialat the provincial artist, the New Wave directors were petits bourgeois, Parisian rich kids making insubstantial films about their little problems, while neglecting the legacy of those they trumpeted (notably Renoir) and pompously rejecting some (like Marcel Carné) whose talents were more formidable than theirs. In Pialat’s eyes, Godard was proud to be better known for what he said than what he did; Malle was a straight-up incompetent; Truffaut (who kick-started Pialat’s career, a moral debt Pialat resented) was fortunate to be making one a year, as his films were so ordinary. His loudest public ire was reserved for Jacques Rivette, whom Pialat considered a monumentally self-important blowhard, whose quest for some sort of verifiable legacy in the face of Godard’s and Truffaut’s success was accomplished by making aggressively boring films. Pialat once cattily told his recurring collaborator Sandrine Bonnaire that she was “good for about three minutes” in the title role of Rivette’s Jeanne La Pucelle (a film that runs over five hours). The acclaim the New Wave directors attracted—and the high ground they claimed for themselves in contemporary French culture—was a source of endless bewilderment and frustration to him.

Furthermore the young turks of the New Wave were the patron saints of cinephilia: an abject concept for Pialat, synonymous with turtle-necked narcissistic fakery. He resented the “rats of the cinématheque,” asphyxiating film’s restorative potential in a poison gas-cloud of turgid chatter. In later life Pialat half-relented (“I should have just kept my mouth shut”), but the extent to which he was jealous, sincere, or ultimately right (or wrong) in his judgment on the value and legacy of the New Wave is far less important to film scholarship than the contribution that this very public estrangement made to his own career. In the final analysis his films belonged apart, because Pialat needed them to.

Indeed, the turbulence of his life and relationships—professional and personal—was wholly indissociable from Pialat’s body of work. His ten features (not counting the dozen or so shorts and one TV miniseries, La maison des bois) constitute from beginning to end a series of autobiographical portraits, throughout which the act of autobiography itself—of laying oneself open to the world—is deconstructed and filleted into its most basic elements. At its crudest level, We Won’t Grow Old Together (1972) is forensic autobiography: a blow-by-blow account of Pialat’s own punishing break up with Colette, a woman twenty years his junior. The quasi-pathological exactness of his approach meant that sequences were shot in precisely the same locations in which Pialat and Colette had slept, eaten, and fought, and he even sought the use of duplicate costumes, right down to the thickness of the stripes on lead actress Marlène Jobert’s bikini. The follow-up, The Mouth Agape (La gueule ouverte, 1974) is a lacerating portrait of his mother’s death from cancer, less anchored in pure fact than We Won’t Grow Old Together but designed to dramatize the same feelings of anger and impotence Pialat himself experienced in the face of his mother’s physical degradation and his father’s cold neglect. With L’enfance nue and Graduate First(Passe ton bac d’abord, 1978), Pialat stepped back from his own specific life stories, but trained his camera on the emotional elements of a childhood struggle which he himself had once known.

As Pialat’s career took flight, with Loulou(1980), À nos amours, and his widest commercial release, Police (1985), he started to take his own history out of his films, while simultaneously ensconcing himself further into them, in more complex ways. His first collaboration with actor Gérard Depardieu, in Loulou, represented the end of his search—after Jean Yanne and Phillippe Léotard—for the ultimate screen surrogate, one he would never contemplate replacing, so perfect was Depardieu’s cinematic persona as an incarnation of Pialat’s combination of softness and rage. Despite this, Depardieu would never play any version of Pialat himself. Loulou is based on a story that happened to Pialat (his girlfriend and close collaborator, screenwriter Arlette Langmann, had left him for a working class yob), but in the film Depardieu plays the ruffian, not the Pialat character. Repeating the dissociative trick with Under the Sun of Satan (1987), Pialat appears opposite the conflicted priest played by Depardieu, as his mentor: as if stepping outside of and protecting this incarnation of himself. In À nos amours, Pialat himself appears onscreen as the father, and elements of this masterpiece—in particular the scenes with Sandrine Bonnaire, then a young debutante —begin to resemble live autobiography, in that they are being lived on camera. His final career pinnacle would be Van Gogh (1991), a towering portrait of the artist he idolized from his youth, allowing him to renew a long-regretted acquaintance with the art world, whilst drawing heavily on the manifold vicissitudes of a creative life which he himself had both engendered and endured. His autobiographical project would culminate in his last film, Le garçu (1995), the title being the nickname Pialat gave his father.

“La method” Pialat

The challenge—and part of the joy—of discovering the cinema of Maurice Pialat has less to do with the fact that there is no outwardly discernible aesthetic “method” than with understanding the reasons why there was no method. For Pialat, cinema itself was its own worst enemy—this did not apply merely, as the New Wave critics would have it, to a certain type of “quality” cinema, but all cinema since the days of Louis Lumière (who in his humility and calculated artlessness, might have got closest to what Pialat himself was attempting). Cinema was simply incapable of achieving what it had wasted most of its efforts striving for, the reconstitution of the emotions and sensations of life. Cinema could only ever imitate them, or loosely illustrate them, but for Pialat it could never get close enough to reality. It used to bother him that even Lumière’s factory workers could not ignore the camera that confronted them as they left work. Pialat’s quest was to abandon this muddy, overtrodden cul-de-sac of reconstitution, and seek out something more artistically valuable and emotionally direct: a cinema of genuine immediacy and truth, a cinema from which fragments of real life could erupt from the screen, where moments could simply exist, freed from the yoke of their context or origins. A cinema where explanation, familiarity, or even understanding were no longer the catalysts for a powerful emotional response to the events being depicted, because the events themselves would carry their own meaning.

In order to achieve this, he put his cast and crew through trying challenges, changing scenes halfway through without warning, ordering take after take until something clicked, without being able to satisfactorily explain what it was he needed. This was not a matter of creating his characters through steady work-shopping in the manner of Mike Leigh: more like the antithesis, rejecting preparation or over-thinking—closer to Cassavetes’s actor-led productions, but denuded of all Cassavetes’s collaborative instincts—instead doing whatever he needed to draw out something unpredictable, when actors were off guard, under pressure, or momentarily lost in their characters. Today, directors reminisce fondly of spontaneous moments on film shoots where something out-of-left-field occurred, which they resolved to retain in the final cut. For Pialat, without this phenomenon occurring on numerous crucial occasions during the shoot, then there was quite simply no film. To choose one powerful example amongst many: The Mouth Agape’s attic sequence, wherein Nathalie Baye and Philippe Léotard read out snippets of letters to one another; the scene seems to drag, until Baye, weighed down by the pain of the scenario and the ordeal of the shoot, overwhelmed by the words she is reading, begins to weep.

Pialat would always force the camera to let what it was showing tell his story, not what it was doing. Critics often talk of long takes in poetic terms (for example, The Mouth Agape—photographed by Nestor Almendros—contains only ninety shots: a fraction of the average number for a feature film), but for Pialat this was nearly always a function of the need to focus on what was being filmed, rather than how. He was equally fond of shot/reverse shot when it served the same purpose (see À nos amours). He’d force his actors—often leading to vociferous disagreements and walkouts—to locate within themselves and offer up to the camera something frequently intangible at first, but of necessity more valuable than what was simply written in the script. Jean Yanne, superlative in We Won’t Grow Old Together, objected constantly to this methodology, as well as to having to portray such an obnoxious character (i.e. Pialat himself) and refused to attend the Cannes Film Festival ceremony to collect his best actor prize, never speaking to Pialat again once filming had wrapped.

Pialat would also teach his audience to forego the trappings of conventional narrative filmmaking, the white noise distractions of exposition and narrative logic that they had come to rely on, in order to bring them closer to a more pertinent, unvarnished—and by necessity simpler—truth. Because of this, many academics and writers would seek to place Pialat in the same lineage as the New Wave, as children of Rossellini (whose neorealism was undoubtedly at the root of such ideas), but the crucial difference is that the New Wave filmmakers deliberately evaluated and conceptualized Rossellini’s approach before taking their cues from it. Pialat, by contrast, was no reverent acolyte of any canon; as a viewer he picked and chose films rather than auteurs (Renoir’s La bête humaine was one of his great favorites, but he considered Le testament du Docteur Cordelier “unwatchable shit”). If his films frequently recalled the best of Rossellini—the couple from We Won’t Grow Old Together could have been George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman from Voyage to Italy transplanted; the sacrificial physicality of Depardieu’s Father Donissan in Under the Sun of Satan owes much to Aldo Fabrizi’s suffering priest in Rome Open City—then there is a strong sense that Pialat arrived there by independent means.

This and his singular (lack of) aesthetic method are some of the reasons why it’s so hard to satisfactorily associate Pialat with any movement or group of other directors. The most convincing—though still not wholly helpful—attempt was made by the film professor and Cahiers critic Joël Magny, who bracketed him with Jean Eustache and Jacques Rozier, unflinching pursuers of the real. Despite superficial similarities, the political tracts of Ken Loach (in their specificity of purpose) and the social dramas of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (who seek a higher, almost metaphysical truth in meticulously recreated “realism”) are quite removed. Rohmer’s “absent camera” invites a comparison that dissolves on contact when you consider the importance of the screenplay to Rohmer’s work. By the time of À nos amours, Pialat was practically ready to work without a screenplay altogether.

True/Truer:

Turkish Shorts; Naked Childhood; We Won’t Grow Old Together (pictured above); The Mouth Agape; Graduate First

When Pialat made Naked Childhood in 1968, it was not quite a debut. He had already made the six films that would come to be known as Turkish Shorts, all of them shot on “borrowed” film stock (stolen, in fact, from Alain Robbe-Grillet who was shooting L’immortelle at the time) with the collaboration of Pialat’s lover Colette (who would run the sound and who would become the subject of We Won’t Grow Old Together) and his cameraman Willy Kurant (who worked with Godard, Welles, and most recently Philippe Garrel; he who would return to Pialat two decades later for À nos amours and Under the Sun of Satan). With these shorts, alternating the movement of Turkish street life and static camera shots, which, in their luminescent composition, approached still photography, Pialat would hone his skills as a documentarian and an observer—rather than a commentator—of the real. The narration on perhaps the most striking of the six films, Maître Galip, is soft-spoken, strangely lyrical, and respectful, giving way in the final moments to images left in silence, which grab the heart.

With the opening shot of Naked Childhood, depicting a CGT teamsters rally (of no narrative consequence to the story, but perfectly placing it into the France of 1968), he continues precisely where he left off stylistically with the shorts, with the only change being the transition to color. In fact Naked Childhood had been devised as a documentary on foster care in France, but during development, Pialat recognized that he needed to reclaim control of the narrative: to extract his truth out of a fiction, rather than risk creating a fiction from within the strictures of factual documentary. In this sense, the personalization of his cinema had begun in earnest. Shot with nonprofessional actors, Naked Childhood depicts the young François (Michel Tarrazon) being returned by his foster family to the social services and rehoused with an older couple, the Henrys, who do everything they can—in vain—to curb his antisocial tendencies (mischief, violence, disobedience). The occasional brutality of the boy’s actions is left unexplained and never condemned: in its place, there is shattering documentary interview–style testimony by Mme. Henry to the social services (the “actress” having been encouraged to take from events in her own life pertaining to her own mother). The nakedness of the title reposes not just on the rawness and savagery of François but also in his objectification (always “he,” never “you”) and lack of the protective clothing of parental love. There’s no question of comeuppance or salvation: the harshness of life is in its lack of resolution. Here is where Pialat finds poetry, carefully avoiding the more prosaic realms of critique or elucidation. The shoot was a constant battle. Pialat had stage fright and doubt at first, delaying production, and later refused the diktat of his production team (Berri and Truffaut, plus Mag Bodard, legendary producer of Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar and Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) that it be edited by a professional, insisting on using his inexperienced friend Arlette Langmann (Berri’s sister) so he could retain control. A useful companion to Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Naked Childhood was a commercial failure, but remains a film of red, raw power and was a vital, now recognized influence on French filmmakers of today, such as Xavier Beauvois and Olivier Assayas.

Pialat was invigorated by having completed his first feature, but he felt stung by the professional conflict involved in the process. He was next awarded a television commission (La maison des bois) in 1970, which he was able to complete with relative creative freedom. With his next feature, We Won’t Grow Old Together, Pialat developed an almost experimental obsession with reproducing the actual events in the breakdown of his relationship with Colette as they occurred, an unsustainable process he would abandon soon afterwards and which makes this film a magnificent outlier. By depicting himself (in the character of Jean Yanne) so riddled with defects, Pialat created a cathartic confessional, apparently exhibiting a directorial self-absorption wholly in keeping with his character’s behavior. Where the film triumphs—and crushes accusations of solipsism—is in its unapologetic rendering of the sheer, damaging onerousness of ending relationships, and in its exposition of French sexual politics of the era (Yanne’s easy ability to “possess” Jobert means he develops a terror of letting her escape). His actors, who experienced the shoot in states of violent dissatisfaction (Yanne) and general bewilderment (Jobert), are nevertheless overwhelming. The candidness of their confrontations is so unusual for major film stars that one senses the ordeal they endured on the shoot has stripped them of all self-consciousness and confidence, both of which would have mitigated the film’s power. Yet Pialat (despite a healthy commercial success, a Cannes prize, and critical recognition) was still unhappy with the results, saying: “In a certain way, someone did manage to make We Won’t Grow Old Together and that’s Jean Eustache with The Mother and the Whore. That’s what I should have done: a four-hour film, a real catharsis which allowed me to puke up my guts. And I should have told those film stars and their sterilizing effect where to get off.”

One can see in The Mouth Agape (about death, but also the impossibility of cohabitation) and Graduate First (about the uncertain future facing French teenagers in the 1970s) bullish retreads of the themes of We Won’t Grow Old Together and Naked Childhood. Pialat pushes the misery, suffering, and pessimism further without approaching exploitation or exaggeration. If he keeps the camera rolling longer than other directors, it’s simply because he’s hammering home the reality that life’s vicissitudes are ineluctable. We don’t get to look away; we don’t get to decide when we’ve had enough.

The center ground:

Loulou (pictured above); À nos amours; Police

A strong desire of Pialat’s was that he not be seen as a marginal director. He sought commercial success like all narrative filmmakers and he coveted critical appreciation more than most, but above all he believed his filmmaking belonged in the center ground: that it should become the way films in general were made. His discovery of Gérard Depardieu took him somewhere close to his wish. Loulou, the story of an incongruous affair between a middle-class girl and an unemployed layabout, was a Gaumont studio effort with big stars, guaranteed a strong commercial opening. Nevertheless Pialat would operate in the same turbulent manner, which meant knocking his stars down a peg: Guy Marchand, as the jilted lover, felt completely ignored by Pialat; Isabelle Huppert was repeatedly told she was hopeless but was not being fired because she was romantically attached to the producer (Gaumont’s Daniel Toscan du Plantier); and Depardieu (the “Loulou” of the title) was leashed by the director to do numerous retakes, as Pialat angrily refused to accept he was giving all he could. Because Depardieu rapidly came to an understanding with Pialat, this last conflict would soon turn to complicity as Depardieu and Pialat traded filthy jokes about the female costars, strengthening their relationship at the expense of Huppert, who stormed off the set (reportedly walking twelve hours through the night to her home) and had to be persuaded by Toscan du Plantier to return.

The resultant work—whose screenplay, such as it was, could not actually be completed, as Depardieu and Huppert had other projects to work on—is more fractious, fragmented, and narratively oblique than his previous titles: a film for which the audience must build up its own response to a mystifying but engrossing sexual relationship based on an accumulation of individual snapshots. Another notable dinner table sequence, this time exterior (a single shot lasting nine minutes, taken with Jacques Loiseleux’s handheld camera), is a remarkable centerpiece that reminds us of Pialat’s taste and eye for the details of simple, provincial French life—the Pastis and oysters, the dog sitting up at the table, the coughing, the furtive looks. What could have seemed like social commentary becomes something more formally vital: a living testimony of the moment itself, with nothing chopped, cleaned, or edited in postproduction.

With À nos amours, Pialat introduced to the cinema—under the eerie, percussive strains of a contralto arrangement of Henry Purcell’s “Cold Genius” aria—the extraordinary Sandrine Bonnaire. An iconic figure in French cinema, Bonnaire occupies a unique place of her own; she was then a working-class teenager with no previous acting experience, whose casting came about because she had accompanied her sister to an audition. Because Pialat was to play her father and because he became captivated by Bonnaire’s talent, his bond with Bonnaire was as intense and ultimately destructive as any other creative relationship he would have. The famous sequence in the film where Pialat remarks that Bonnaire appears to have lost one of her dimples when she smiles (improvised from an off-screen conversation the previous day) and in which Bonnaire for her part remarks that Pialat’s eyes look bloodshot, illustrates their unique closeness while foreshadowing their eventual falling out. Their parting at the end of À nos amours (while having no tragic dimension in itself) is as emotionally staggering as it is understated, provoking in the audience—through Pialat’s refusal to tidy the background noise or compose the images to reflect the scene’s colossal emotional importance—a sense of burning emptiness, unique to the director’s work. Pialat would treat Bonnaire vengefully on his next film, Police, as he could not abide her desire to work with other directors after he had launched her into the business; he gave her the ungrateful bit role of a whore, while Sophie Marceau (whom in reality Pialat had little time for) took the lead. Though they revived their collaboration with Under the Sun of Satan, in which Bonnaire gives a remarkable performance, their ultimate estrangement in the wake of her stratospheric ascension would always heavily on both of them.

Police is notable not just for being Pialat’s only attempt at a purely commercial venture (a procedural) and for Catherine Breillat’s tireless work on the screenplay (immersing herself in the world of Parisian vice squads), but also for containing Depardieu’s least feted, yet perhaps most liberated Pialat performance, as a cop who falls for Marceau’s unwitting femme fatale. Where Loulou shows Depardieu being put through the ringer by Pialat, and Under the Sun of Satan finds him stretching—sometimes with difficulty—toward a more classical performance, his Detective Mangin in Police is a rare example of an actor wrestling control of the role from his director. It certainly helps that this is a rare Pialat film with a strong screenplay, but Depardieu’s juxtaposition of violent machismo and utter impotence is one that would come to characterize his career. One can be permitted to see in it an impertinent half-portrait by Depardieu of Pialat himself—one partly indulged by the director, so daunted was he by the actor’s talent.

The consecration of a master:

Under the Sun of Satan; Van Gogh (pictured above); Le garçu

Under the Sun of Satan was another eyebrow-raising departure for Pialat after Police, regardless of Pialat’s outspoken reverence for writer Georges Bernanos. (Robert Bresson, one of the few masters Pialat truly revered, had also adapted Bernanos in Diary of a Country Priest.) After all, what could Pialat possibly expect to do with this hallowed literary material—a story of God and the Devil, whose metaphysical dimensions were worlds away from his usual earthly concerns—which could place it in the register of À nos amours or Naked Childhood? As it happened, the pressure of the text would engender a chaos and a paranoia all its own. On one occasion, producer Daniel Toscan du Plantier arrived on set to find the cast and crew effectively held hostage, as Pialat had locked himself in a room and forbidden anyone to leave: his door was forced open and he was dragged out. As always, Pialat had made his actors and crew suffer, but also, on this occasion, himself. The sacrifice made by Depardieu’s priest, Donissan, in the service of the salvation of a young girl, Mouchette (Bonnaire), was being mirrored in the sacrifice Pialat was making of his own health, for the good of the film. As a matter of record, he had decided to make the film because he saw in it an opportunity to win the Palme d’or at Cannes, which he duly received, under a rain of catcalls and whistles. Stung by this cruel reception, he addressed the crowd: “You may not like me. But you need to know that I do not like you,” and raised his fist in defiance.

His adaptation was one of violence toward the text, scrapping swathes of plot and removing temporal elements, speeding up the book, multiplying the confrontations. Retaining only Bernanos’s plot, Pialat reduces the story to the realities and experiences of key figures Donissan, Mouchette, and Depardieu’s character’s mentor, who cautions him against the untrammeled vigor of his faith and is played by Pialat. His physical grappling with Depardieu at a climactic moment reminds us how often Pialat films the pathetic clutching and brawling of bodies, when words ultimately fail his characters: in À nos amours, of course, but also Loulou, where the friends gang up on the irascible Thomas, who has brandished a rifle to shoot a supposed love rival, and right back to the almost unendurable sequence of Naked Childhood in which the kindly M. Henry and the stepbrother wrestle François to a standstill in silence before thrashing him. The reversion to the physical, for Pialat, is both a tragic inevitability—an admission of defeat—and at the same time part of the lifeblood of his cinema: bodies constantly in a state of magnetic attraction or repulsion, striking each other, clawing and pulling. In their brute strength lies a palpable, lamentable weakness.

Before returning to direct autobiography for his final film, Le garçu, in which he would directly take on his vexed relationship with his father, Pialat had one more project, decades in conception, to complete: Van Gogh. Understandably appalled by the prospect of making a conventional biopic of the artist—a point of view many directors could since have benefitted from—Pialat made Van Gogh one of an ensemble cast and chose to elide almost all sequences of actual painting. Incarnated by an ascetic Jacques Dutronc, the painter himself does not need to appear constantly onscreen to be the subject of the film: secondary characters (his brother Theo; his host and doctor, Gachet) allude to him constantly, even when apparently discussing something or someone else. For Pialat, if Van Gogh was a genius whose impact on the following century was immeasurable, he didn’t know this and wouldn’t have cared if he did. Pialat was more interested in the artist as a witness to the period in which he lived—which is arguably what made him great. So Pialat reverts, as so often, to the quotidian details of life during a spell of convalescence Van Gogh spent at Auvers-sur-Oise (actually shot in Richelieu, fecund location of Roman Polanski’s Tess, Raúl Ruiz’s Time Regained, and Olivier Assayas’s Les destinées). Another table scene, with diners humming the French folk song “Le temps des cerises”; one of the characters describing her dead child; the piano teacher singing Lakmë in the bar—all these moments combine to create the expressive canvas of Pialat’s film, a breathing work of art.

It’s a story like his own—of an artist who inspired awe, but who never enjoyed a sense of his achievement while alive. Pialat himself died in agony of kidney failure in 2003, having broken contact with Bonnaire, Yanne, Dutronc, Jobert, Toscan du Plantier, Berri, Huppert, and a string of other collaborators. Only Depardieu, of his professional partners, was there at the end. Pialat wasn’t aware how much the others revered and loved him, because he had pushed them away. His thirst for discord in his work had spilled into his life, because he could not separate them. All of his art grew from the pursuance of ideas and methods that many others would have abandoned as injudicious or cruel: he worked in the “now,” and regrets could wait—but they always came.

A word you will never see used to describe a Pialat film is “perfect,” because for him an artist was one who created to pursue a treasure that was within him; and what was within Pialat was imperfect, and what was outside him even more so. In his quest for a canvas from which, at any moment, light and truth could explode in the spark of an instant, he sought out the tears in the fabric of life, the battlegrounds, and the dying light of doomed relationships. His films are replete with yawning gaps and cracks between the vivid, precious moments of truth—and all that can fill them is an inexorable, inescapable sadness.