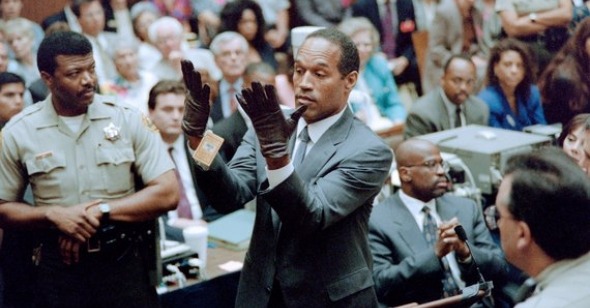

Best ESPN Miniseries: OJ: Made in America

This mesmerizing, multilayered production from ESPN for its 30 for 30 documentary series was a continually regenerative and revealing investigation into OJ Simpson as both man and symbol, while never losing sight of the larger societal and sociological forces that both created his public identity and conspired to allow him to get away with murder. This television show, nearly eight hours in length but made digestible for home viewing because it was divided into five segments of approximately ninety minutes each, is a marvel of editing and dialectical inquiry, endlessly searching yet confident that the indirect lines it’s drawing between the decades of racism and urban unrest in Los Angeles in the second half of the twentieth century and the lead-up and public response to the beloved African-American athlete’s acquittal in the murder of his long-abused wife will bear dramatic fruit. After watching this absolutely penetrating, perfectly structured episodic television study of this era-defining event, which passes from OJ’s childhood to his football and post-sports entertainment careers and on to, most extensively, the televised courtroom drama that became a part of nearly every American’s living room in the mid-nineties, any attentive viewer will no longer be able to think of the murder trial as a contained event with its own beginning and end. This devastating television miniseries reminds you that history—personal or public—exists on a continuum. Check it out on ESPN or Hulu or other channels for your television. —Michael Koresky

Best Ending: The Lobster

Yorgos Lanthimos’s move into the international coproduction arena proved bitterly divisive among critics both when it bowed at Cannes in 2015 and during its theatrical release this year; a few high-profile writers treated the film with the same abject, arbitrary cruelty that they perceived in its story of singletons signed up (or is it forced?) into elaborate mating rituals in an isolated hotel at the edge of a fairy-tale forest. To which I say, fair enough: like its namesake, The Lobster is so cold and spiky that it’s pretty hard to love, and yet no final scene this year left me feeling as complex a mix of emotions as Lanthimos’s finale, which finds lovers-on-the-run Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz hiding out in a diner and planning their next move. Weisz’s character has already been blinded by anti-monogamy activists, and when Farrell excuses himself to use the washroom, we know it’s because he’s considering taking out his own eyes—a play on the idea that “love is blindness.” In Dogtooth, Lanthimos contrived a similar moment for the express purpose of depicting self-mutilation, but here he holds the camera on Weisz while we wonder what her partner is up to. Is he trying to level the playing field between them, or is a relationship something that can only be entered with eyes wide shut? Or has he run out the back door and left her in the dark? The ambiguity here isn’t simply a matter of open-ended narrative gamesmanship, but the culmination of a movie that scuttles agilely and elusively between plausible pathology and stark, fable-like abstraction. —Adam Nayman

Best Hitchcockian Cameo: Kenneth Lonergan in Manchester by the Sea

Deep into Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea, Casey Affleck’s Lee gets into an argument with his orphaned nephew, Patrick (Lucas Hedges), as they walk to the car. A passerby catches a whiff of the spat and blurts out, “Nice parenting.” Lee, who’s more than happy to throw down with anyone, almost gets into a fight with the stranger—played by Lonergan himself—but Patrick breaks them up and the man walks away. Scene over—but not quite. For a few more seconds, the movie cuts away from our protagonists and follows the stranger up the sidewalk as he takes a quick look back. In Lonergan’s movies, the world on the screen is always spilling over; micro-stories and hinted-at lives branch out like tributaries from the main narrative. (Another favorite moment: that shot of the back of Matthew Broderick’s head—you can feel his ears burning—as he walks away from being ridiculed by two stoned students in Margaret.) A stranger walking into a scene can be just a catalyst for action; staying with him after his purpose has been exhausted suggests a recognition that there are other stories out there. It’s a paradoxical thing: a director keeping the camera on himself being a sign of generosity. —Elbert Ventura

Most Unflinching: ’Til Madness Do Us Part

The epically scaled films of Chinese documentarian Wang Bing are beginning to win the recognition they deserve in the U.S., but they still remain underscreened. This past year New York’s invaluable Anthology Film Archives gave a full week to Wang’s four-hour trip into the hell of a Chinese mental institution, and those who ventured into the theater likely left its tour of horrors different viewers. This is not merely due to the events on display, which run the full gamut, and more, of what one expects to see in mental institutions. This one, we’re informed at the film’s end, is typical for the Chinese system in that dissidents, political operatives and small-time criminals are imprisoned with patients suffering from actual mental disabilities, and you can almost feel the saner patients deteriorating as the film goes on. What’s perhaps most shocking is not what we see but how we see it, via Wang’s bravura, long handheld takes, some of which seem like they stretch for hours as he follows the subjects wandering the halls of the facility. His camera places us right there, in ways few documentaries allow themselves the leisure to do. We’re so immersed that when the film leaves the institution for a time late in its third hour, the result is an unlikely epiphany that lasts for a few moments until Wang plunges us right back into the inferno. He’s a filmmaker who doesn’t believe in half measures or looking away. We all could use to see more of what he sees and how he sees it. —Jeff Reichert

Foulest Trailer: Deepwater Horizon

Did you know the “true story” of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill—you know, the worst ecological disaster in U.S. history, whose months-long belching of oil, estimated to be near five million barrels, would ravage a coastal region for decades to come? The truth actually concerns the courageous exploits of a single man, who, as the trailer tells us, is a “real life hero”? The kind of guy who remembers to save an excavated dinosaur tooth to give to his daughter, and whom Kate Hudson calls a “good man” on a Skype call, and who is respected and smiled at by his co-workers? In between shots of digital pyrotechnics and the building strains of the truly execrable song “Eye of the Storm,” the trailer offers this solemn, all-caps platitude: “In our darkest hour, courage leads the way.” Right out of the theater, one can only hope. —Genevieve Yue

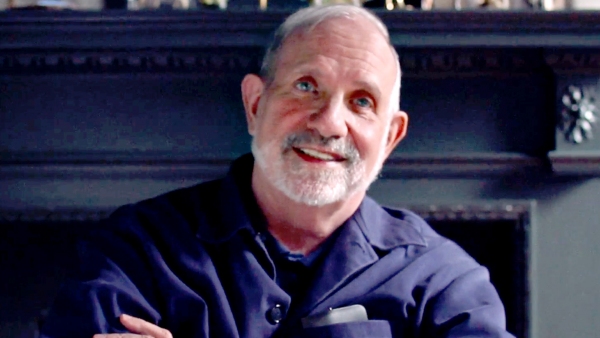

Worst De Palma Critic: De Palma

Take it from a staunch Brian De Palma addict: Brian De Palma is the person you least want to hear talk about le cinéma de Palma. Sitting awkwardly before a fireplace mantle in Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s talking-head doc, the now enormous De Palma holds court, going through his films chronologically, one by one, relating some terrific anecdotes, and overall being a surprisingly genial guide. The result is an aesthetically impoverished documentary about a great visual thinker—a disconnect hard to get over—but more detrimentally, his perspective on his own work’s merits is mostly tied to financial success (as is the case with many American filmmakers, including Spielberg). Thus, De Palma reiterates that his greatest accomplishments are benchmarks Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Scarface, The Untouchables, and Mission: Impossible, while such relative box-office disappointments as The Fury, Raising Cain, and Femme Fatale get short shrift—especially the latter, which barely rates any screen time even though any true De Palma fan knows it’s a career-defining masterwork. There’s a purity of vision and concept to Baumbach and Paltrow’s approach for sure: wind up the man and let him talk. But if there’s any filmmaker whose work is worthy of a more dialectical approach it’s De Palma, one of our most hotly debated, divisive directors. Like any artist, his work benefits from considered, serious criticism. (If you really care about De Palma, read Chris Dumas’s brilliant recent book Un-American Psycho, an engaging and endlessly revealing political and aesthetic study.) De Palma provides us with a rare home visit with an elusive figure, but its anti-critical approach left me thirsty. —MK

This Must Be the Place: Homo Sapiens, The Illinois Parables, Cameraperson

For at least three 2016 documentaries, location, location, location was everything, or most. All three foreswore talking heads and straightforward narratives, and placed “the space” above all else. But humanity of various stripes was all the more conspicuous by its absence. Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson has plenty of people in it, but some of its strongest moments are strung-together shots of places: in one striking montage Johnson identifies in each an atrocity that occurred there. Most remarkably, it manages to be an autobiography of sorts, even though Johnson only visibly flits by once. In The Illinois Parables, Deborah Stratman forges an eccentric history of that state mostly by just shooting the places where history happened, filling in just enough information where needed (and in one instance, a starkly funny assassination recreation acted out by barely there, zombie-like stand-ins). But with Homo Sapiens, Nikolaus Geyrhalter gets at the heart of the matter with his title alone. His film is a series of stationary shots of developments and structures (strip malls, rollercoasters, temples) constructed by men but since abandoned, and the (beautiful) unpeopled frames only serve to highlight the indelibility of humankind’s imprint on the world. Homo Sapiens’ worldview might be a bit bleaker than the other two, but it shares a belief that a place’s history is never just its past. It’s almost a belief in ghosts. —Justin Stewart

Biggest Missed Opportunity: Aquarius

Without the support of a major mini distribution company or an indie studio branch, Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho’s astonishing Aquarius more or less went unheralded outside of small cinephile circles upon its theatrical run from tiny Vitagraph last October. While the company that released it should clearly be commended rather than criticized for ensuring the release of one of the year’s very greatest films—a stirringly political film that also manages to be an internalized character portrait—it’s hard not to fantasize what a well-funded marketing campaign from, say, Sony Pictures Classics or A24 might have been able to do with it. There was controversy to mine: upon its premiere in Cannes, Mendonça became the target of conservative attacks when he spoke about the forces conspiring against eventually ousted President Rousseff back in Brazil. There is a mesmerizing central performance by a legendary grand dame worthy of awards: 65-year-old Sonia Braga, magnificently sensual and cerebral as a retired music critic standing up to the ruthless real estate company trying to force her out of her beloved seaside apartment to convert it into a luxury condo. There is a political message of the importance of resistance that feels particularly crucial in our nightmarish Trump era. On top of all that, it’s as accessible and crowd-pleasing as an artistically significant art-house release is going to get. Despite this, it had barely a push, and many critics who write for this publication didn’t even bother seeing it; despite that, it still made it to the number five slot on our top ten list, a testament to the high-ranking passion its supporters feel for it. Surely it will find its audience. In the meantime, let’s keep debating who should win best actress: Fox Searchlight’s Natalie Portman or Lions Gate’s Emma Stone. —MK

Bad Dad, Movie Edition

Because I have a five-year-old, I have become something of an expert on the contemporary kiddie movie landscape. And I am here to tell you: Illumination Entertainment, makers of those damned Minions, is a blight. This year, Illumination dropped two movies that combined made a gazillion dollars and my daughter happy: The Secret Life of Pets and Sing. Both are wretched products, unashamed about their laziness and lack of ambition. If Pets wasted its premise by going the slam-bang theme-park route, Sing is a soulless revue that plucks the lowest-hanging pop fruits (and drops them anyway). The output from the Disneys and Pixars, not to mention Laika (though my daughter is too young for the terrific Kubo and the Two Strings—that one I saw for myself!), has not been uniformly great, but there’s a baseline of invention and creativity that I have come to expect and appreciate. A kindergarten docent into cynical mass culture, Illumination has fooled this dad for the last time. —EV

Cred Herrings: La La Land

Fans of La La Land simply won’t hear it when heartless cynics—or, better yet, “disaffected” critics—imply that Damien Chazelle’s film is anything less than totally lovable, and far be it from me to tell people that they’re wrong for liking or not liking something (that’s for fans of La La Land to do on Twitter). Instead, I’ll pose a question: can anybody who truly adores this movie account for why Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) never exchanges a single audible line of dialogue with all the venerable black jazz musicians he moonlights with in between his solo piano-man gigs, or the black revelers dancing so ecstatically to the songs he’s playing?

It’s at once a real critical imperative and sincerely risky business to bring up racial politics in film analysis in 2016, when the question of who gets to write about movies (and for which publications, and for how much money) is a rightful topic of debate and reform right alongside who gets to make them, and also when issues of identification and representation can just as easily close off discussion of a movie’s contents as open them up. It is probably unfair to impute any ill intention to La La Land’s blindingly white Los Angeles backdrop. At the same time, the way that Chazelle narrows his narrative focus following the opening ethnic-panorama production number points to a Hollywood status quo being rather unimaginatively upheld—and the conventionality is exacerbated by the fact that the director’s gently charming 2009 debut Guy and Madeleine on a Park Bench wrapped its low-fi song-and-dance numbers around an interracial romance. In La La Land, African-American musicians are rendered (as in Whiplash) as measuring sticks for an ascendant white performer’s monomaniacal notions of “purity,” while African-American actors are either used as benign props—as when Sebastian encounters a sweet (and totally mute) old couple while singing to himself at the end of a pier—or else as signifiers of authenticity (Gosling’s exuberant club-land buddies) or a lack thereof (John Legend’s smoothie sell-out, who may not be the villain of the piece but doesn’t make much sense as a character anyway).

In a present-tense film whose featured lovers both long, in ways tacitly endorsed by Chazelle’s fetishistic retro aesthetic, for a return to the eternal showbiz verities of boy-meets-girl enchantment, the near-total effacement of the host city’s actual demographics and social makeup—as opposed to the knowingly phony studio-lot sets that act as backdrop for several scenes—has (purposefully or not) a reactionary aspect. It’s not about asking one poor, defenseless little Best Picture front-runner to solely bear the weight of systemic industrial issues so much as examining what is suggested by its near-consensus standard-bearer status. And if the best that can be said is that it’s no worse than most other American movies in this regard, let’s just say that I’ve seen better reasons for celebration. —AN

Best Tag Teaming: Sunset Song

When word came out a couple years ago that Terence Davies not only got funding to shoot one of his long-gestating dream projects, but that it would be shot in part on 65mm film, any right-minded cinephile had reason to be excited. And indeed the sweeping, outdoor vistas, mostly shot in New Zealand, are wholly glorious (especially when watched on the massive scale of an IMAX screen at the Toronto International Film Festival—a once-in-a-lifetime memory to cherish). But the exquisite surprise was that the digitally shot interiors are perhaps even more breathtaking. Davies said he was inspired by the work of Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi in fashioning these intimate sequences, some by evocative candlelight, others with afternoon sun streaming expressively through windows. The handoff between film and video becomes a one-upmanship game of sheer beauty—one thrilling composition after another that leaves you believing in the power of digital as much as the glory of film. That’s a win for everyone. —MK

Hardest to Read: Golshifteh Farahani’s Laura in Paterson

She stays home all day. She cooks and cleans. She plays guitar and paints. She’s supportive and sweet, unfailingly encouraging her husband to write his poetry and follow his dreams. Does Laura, the girlfriend of Adam Driver’s bus driver in Jim Jarmusch’s intoxicating ode to the importance of the creative spirit and seeing the world and people around you, represent an outmoded type of woman, a traditionalist image of a homebody inhabiting strictly feminine domestic roles, as many detractors have claimed? And is her art, including goofy paintings of the couple’s bulldog Marvin, “bad”? Is her cooking, such as a Brussels sprouts and cheddar cheese pie that Driver for some reason can’t seem to swallow, actually terrible? Is her taste in black-and-white patterned décor adorable or awful? Is she an unrepentant dilettante or does she have the soul of an artist? That none of these questions can be easily answered by the film, which is driven by Driver and Jarmusch’s respective brands of detachment, reminds the viewer that much remains in the eye of the beholder when you watch a movie, especially in movies that take matters of taste and art as central motivating forces. —MK

We Don’t Need Another Superhero: Batman v Superman

The sheer disorientation of watching Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice is such that it’s possible to mistake Zack Snyder’s sloppiness for something unusual and even visionary. The film has a few absolutely striking images, like Henry Cavill’s Superman touching down amidst the revelers at the Mexican Day of the Dead—a pensive, diffident God amongst the mortals. Snyder’s skill at sketching superhero pietas is formidable (as it was in Watchmen), but he’s utterly hopeless as a storyteller, to the point that basic character motivations are rendered unrewardingly mysterious and subplots alternately overwhelm the narrative momentum or grow moldy with neglect. In trying to bridge several different comic-book properties—not just Batman and Superman but also Wonder Woman and, in one bizarre interlude, an entire pop-surrealist dreamscape’s worth of lesser DC Comics denizens—he flunks the world-building assignments aced by lesser stylists under contract to Marvel. BvS comes at us in big, unwieldy chunks of exposition laced with grandiose juvenilia, the latter personified by Jesse Eisenberg’s incessantly Millennial Lex Luthor, whose plans are so simultaneously vague and convoluted that the arrival of some blurry monster or other to enact destruction comes almost as a relief . . . that is until his rampage eats up what feels like an hour of screen time on top of the protracted, eponymous bout. —AN

Best Omniscience: Right Now, Wrong Then

Worst Omniscience: 11 Minutes

The bifurcation and replication Hong Sang-soo employs in Right Now, Wrong Then gives the sense that not only the filmmaker and his audience know how badly things played out in the film’s first half, but also that the movie and its characters know too, and act accordingly to much different results in the second. With everybody in on the gag, authorial omniscience results in agency for all—we’re free to ponder a multitude of different relationships between the film’s two halves. Right Now, Wrong Then as a viewing experience feels a culmination of Hong’s accumulated experiments at twinning and doubling back. Meanwhile, the constant splitting of Jerzy Skolimowski’s 11 Minutes across its many scenarios over 11 minutes in their lives not only grows tiresome, but seems little more than manipulation once the climax, in which all the stories intersect, is reached. I’m sure Skolimowski could mount a reasonable case for why, at this late date in his career, he’s aping early Tom Tykwer, but that still wouldn’t save the film. —JR

A New Mope: Rogue One

Legend has it that the working title for the third Star Wars franchise movie way back in 1983 was The Revenge of the Jedi until George Lucas suggested that vengeance was unbecoming of a gallant order of galactic knights. In trying to figure out why I had such a dismal time at Rogue One, I wondered if it was because the film is, at its core, a revenge story. Heroine Jyn (Felicity Jones) has an axe to grind against the Empire because it enslaved her father to help build the Death Star, and so her campaign to lead rebel forces on a kamikaze mission is equal parts personal and political—less a call to adventure than a settling of accounts. It’s not that grit and grimness don’t fit in the Star Wars universe so much as they have to be carefully blended in to the overall palette, and Gareth Edwards goes way too gray-scale with the material. The modest but real charm of The Force Awakens lay in the expressions of surprise and delight between the actors (John Boyega and Oscar Isaac, especially)—the same rascally attitude conjured up long ago/far away by Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher. Rogue One is wholly po-faced and comes off as a slog, right up to that CGI-drenched would-be grace note that ironically only serves to remind us of the humanity absent from this act of brand extension. —AN

Moonlight MVP: Ashton Sanders

The middle child always gets ignored. There is a wealth of extraordinary talent onscreen in Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight, but it’s been frustrating to see Ashton Sanders, who plays high-school age Chiron, get lost in the shuffle. For this viewer, Sanders—with his crumpled physicality, his body always seeming to fold in on itself—was the true face of Jenkins’s gorgeous coming-of-age film, his entire bearing evoking both the universal experience of growing up feeling different and the very specific experience of growing up as a gay, African-American male in Miami. It’s this cultural and psychological specificity that makes Moonlight such a special film, and Sanders, with the slightest of gestures, expresses it in every moment. —MK

Best Raging Bull: Robert De Niro in Dirty Grandpa

Like many other worthy comedies distributed in the drippy doldrums of late January, Dirty Grandpa was stomped on by cruise-controlled critics who took its release date and narrative scenario—a mouthy old horndog tries to re-enact Spring Breakers with his grandson in the name of inter-generational bonding—as indicators of de facto badness. Au contraire: this second film by the Oscar-nominated Ali G and Borat scribe Dan Mazer is a work of surprisingly clear-eyed vision: it’s a 90-minute leer in the general direction of Zac Efron, whose good-sporting, essentially decorative presence—i.e. stumbling around a police station lockup in an orange crop top reading “Stop Staring at My Tits”—gently redirects the masculine thrust of the material. The satirical key is the contrast between Efron’s hard-bodied blitheness and De Niro’s spirit-is-willing/flesh-is-weak intensity as the titular Grandpa; the way that the older man simultaneously resents, envies, and competes against his genetic inheritor is funny and truthful in ways that transcend the drab formalities of the plot. To some extent, Mazer is exploiting his gleefully slumming star’s aura, but darned if De Niro doesn’t seem more liberated than in any role in recent memory. This is what committed comic acting looks like. —AN

Best Landscapes, Big Sky Edition: Certain Women

For someone whose movies are known for their quiet scenes and murmured truths, Kelly Reichardt has given us some of the most indelible landscapes in American movies. In Certain Women, those mountains in the Montana distance don’t evoke western freedom so much as loom over the figures on the ground, walling off possibilities. Denizens of a downbeat America, Reichardt’s women are among the sharpest evocations of contemporary loneliness in the movies. Life has never seemed so limited, and the frontier never so oppressive. —EV

Clunkiest Line: Mountains May Depart

“It’s like Google Translate is your real son!”

Best Musical: Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping

Clocking in at a very respectable seven out of eleven on the This Is Spinal Tap rockumentary meter, Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping also moves the needle forward on the Lonely Island’s forays into feature filmmaking. In lieu of the goony stupidity of Hot Rod and the intermittently undisciplined Golan-Globus pastiche of MacGruber, co-directors Jorma Taccone and Akiva Schaffer delivered a slickly packaged critique of music industry fickleness and fecklessness—both nicely personified by the group’s frontman Andy Samberg as the professionally inauthentic “Conner 4Real”—that failed to entice audiences used to consuming the group’s work for free in three-minute doses on YouTube. The MTV-clips-within the film are mostly hilarious, especially “Equal Rights,” which features a reluctant Pink singing the gay-and-proud hook in between Connor’s cluelessly counterintuitive alpha male boasting (ditto the Kanye West-esque, Adam Levine assisted “I’m So Humble”). What makes Popstar so enjoyable as a musical, though, is its insistence on the importance of collaboration, more joyous and less pious than the last-angry-jazzman rhetoric of La La Land. The agony here isn’t over “selling out,” which in this—much more realistic—La La Landscape is a given for every professional (even Chris Redd’s outrageous Tyler the Creator manqué, whose killer track is titled “OJ Plympton”). Instead, Samberg slyly and affectionately self-allegorizes his anxieties over his own breakout stardom at the expense of his long-time bandmates. Conner’s climactic decision to reunite and perform with his old bandmates, the “Style Boyz” (played by Taccone and Schaffer), instead of advancing his own solo brand underlines the communal joy of music-making, even when the music in question is a) really dumb and b) features Michael Bolton. “Incredible Thoughts,” that one’s called, and while the joke may actually be on the Style Boyz for mistaking their neural firings (“What if a garbage man was actually smart?”) for mystical insights, I’d like to remind you of something that a wiser man than you or I once said: there’s a fine line between stupid and clever. —AN

The Herman G. Weinberg Award for Contributions to New York Film Culture

The award goes to Brooklyn-based collective Mono No Aware, for raising enough contributions to open the country’s first nonprofit film lab, and for hosting—on the occasion of its tenth anniversary—one of the year’s best film series: an eclectic month of screenings that mixed revelatory rarities by Gordon Matta-Clark and Carolee Schneemann with work from young moving-image artists like Erika Jane Barrett and Tzu-An Wu. —Max Nelson

Weirdest Riff: Miles Ahead

Don Cheadle’s heart was undoubtedly in the right place when he chose to co-produce, co-write, direct, and star in this kinda-biopic of Miles Davis. Cheadle is a massive fan and the idea of his playing the legend had been floated by Davis’s nephew. The portrayal here is unimpeachable— more than just accurately mimicking Miles, Cheadle captures both the aloof sadness and bitter anger that characterized the man, and the trumpeting is credible. But the decision to fixate on Miles’s “silent period,” roughly 1975 to ’79, when he was strung-out and creatively and physically drained, and the choice to fashion a sort of madcap heist comedy out of it, are baffling. Miles’s theft of his own recordings from his label might be historically accurate, but the resultant car chases and undignified buffoonery are a jarring contrast with the few snippets of Cheadle as the dapper, more serious 1950s Miles. The abundance of real Miles tunes and an affecting performance by Keith Stanfield are bright spots, but, as authentic as the jheri curl may be, it’s dubious that the world needed to see Miles scoring coke from a white nerd in a dorm room. (Less authentic is the Cincinnati shooting locations, better utilized and camouflaged of late in Carol.) —JS

Best Use of a Bad Song:

The Knack’s “My Sharona” in Everybody Wants Some!!

Worst Use of a Good Song:

Thelonious Monk’s “Japanese Folk Song” in La La Land

Survive the Night: Hush, Don’t Breathe, The Invitation

It was a good year for horror films, especially those set in one location over the course of a single bloody night: Mike Flanagan’s tense Hush, in which a lone, deaf woman must fend off a murderous psychopath in her remote house in the woods; Fede Alvarez’s brutal Don’t Breathe, in which desperate teen robbers are trapped overnight in a fight-to-the-death in the house of a shockingly resourceful blind widower and veteran; and Karyn Kusama’s suspenseful The Invitation, in which a dinner party segues into the worst self-help session of all time. Each is a study in precise, economical filmmaking, fine-tuning every gesture and movement, shot and cut, down to its basics. In each case we pray for sunlight. —MK

Best Hero: Logan Marshall-Green in The Invitation

Standout performances in genre films rarely if ever get the credit they deserve, even though the extraordinary situations of their plots often demand a level of psychological and physical investment you don’t see in more respectable prestige products. With his flowing locks, kissable Tom Hardy lips peeking out from a meticulously groomed beard, and richly skeptical eyes, Logan Marshall-Green could have easily been written off as a pretty-boy protagonist in Karyn Kusama’s splendidly scary The Invitation. But he brings intense pathos and genuine emotional commitment to his role as a man with a tragic past who gradually realizes that something is very, very wrong at a dinner party hosted by his ex-wife (an ethereally sad Tammy Blanchard). We see the unfolding events through his eyes, and feel his confusion, pain, and fear every step of the way; meanwhile, at the center of this unexpectedly fine horror film is an investigation of the grieving process that has more in common with Manchester by the Sea than one might expect. Marshall-Green deserves to share some of those Affleck accolades going around. —MK

The Paul Giamatti Award for Overacting: Natalie Portman in Jackie

In the voice of South Park’s Cartman mixed with a Marilyn Monroe-impersonating drag queen:

“Misteh Valenti . . . would you mahnd getting a message to ool aww funeral guests when they lehnd? Infoohm them that I will whoa-wuk with Jack tomorrow . . . Alone if necessary. And tell General de Gawul that if he wishes to rahd in an uh-merd cahhr—or in a tank, fuh that mattuh—I won’t blame him. And I’m shoo-uh the tens of millions of people oowahhtching won’t eye-thuh.” —MK

Can't-Take-Our-Eyes-Off-Her Award: Amy Adams, Arrival

Dedicated readers of this column will note that Amy Adams is the usual winner of this prize, for better (The Master) or worse (American Hustle). So what do we make of Adams's performance in Arrival? As a woman endeavoring to save the world while also processing some level of profound personal grief, Adams is a wonder to behold in Denis Villeneuve's sci-fi epic. The movie leans heavily on her. If there is a singular image that defines Arrival, it is Adams's face in close-up, as her linguistics professor struggles to find a common language with the aliens who have descended unexpectedly on earth. Somehow—quite improbably—Adams represents everything 2017 most desperately needs. Staring into her soulful eyes, you might believe that humanity could be capable of transcending its worst instincts, of finding something good in all of us, and leaning in to that optimism. Unlikely as it might seem in the era of Trump, Adams salvages something genuinely hopeful...a wide-eyed view of our best selves. —Chris Wisniewski

Worst Performances: Forest Whitaker x 2

Forest Whitaker is someone I thought I admired until confronted with the stench of his two terrible performances this year. In Arrival, his Colonel Weber is useless and tedious. Some of this can be attributed to lazy plotting (it’s not Whitaker’s fault that his character sought the help of a one-time Farsi translator, thinking that was a unique qualification for comprehending an alien language) and a clunky script (he gets the lion’s share of expository dialogue, with gems like “Dr. Banks, figure something out”). But his borderline somnambulant performance is all his own, as is his wandering accent, which travels from Boston to Scotland to, possibly, Jamaica. His turn in Rogue One is, by contrast, more coherent, but still not in any sensible way; inexplicably he plays the mad-dog rebel Saw Gerrera as a just-electrocuted Teletubby. Whitaker had an effect on his scenes like the anchor Rodney Dangerfield drops through Ted Knight’s boat in Caddyshack. It was docked to begin with, and now it will never sail. —GY

Best Goat: Black Phillip in The Witch

Worst Goat: Goat

The Frank Sinatra "All the Way" Award: The Wailing

For two and a half gripping hours, Hong-jin Na holds the viewer in the sweaty palm of his hand in telling his endlessly inventive tale of possession, murder, and the occult. One of the year’s best horror films, this Korean supernatural policier cum domestic drama (with a little zombie flick thrown in) builds to an unforgettable conclusion, with imagery designed to haunt dreams. Upon my late-night viewing experience, when the film finally ended at 2:30 a.m., I was disturbed enough to lie awake another hour before falling asleep. What kept me up was partly the creepy content of the ending itself, of course, but also that I couldn’t stop thinking about how the director just really went for it. Not with regards to violence or gore, but in terms of a pure, distilled expression of the triumph of evil. Call this ending the anti-Aquarius. —MK

Worst Cameo: Keanu Reeves in The Neon Demon

That it was only a dream doesn’t eradicate the distaste of the scene in which Reeves mimes a blowjob with a hunting knife on sleeping teen Elle Fanning. That it wasn’t even the most disgusting part of the always disgusting Nicolas Winding Refn’s disgusting movie says a lot about this film’s depths of smug depravity. —MK

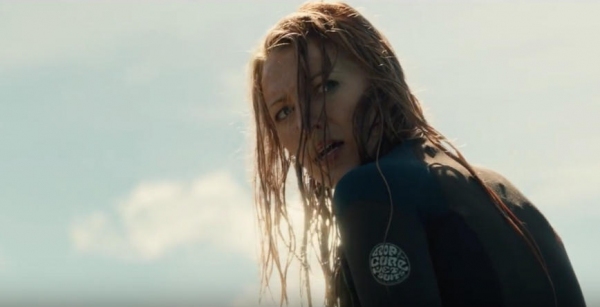

The Jaume Collet-Serra Award for Achievement in Films Directed by Jaume Collet-Serra: Jaume Collet-Serra, The Shallows

Let it be known that we are planning to retire this award, bestowed now for six years running, and here’s why. Our once (and future?) cult hero spent the summer months of 2016 fending off a bevy of overheated suitors bearing roses in the form of breathless print-and-online-media encomiums, The Bachelorette-style, to the crafty Catalan’s genre-savvy directorial chops (including a very fine appreciation by Nick Pinkerton in the pages of Sight and Sound). These gifts were surely on display in The Shallows, a likeable and effective film whose virtues and flaws have already come in for more word-count scrutiny than the collected works of Straub-Huillet (and inspired some of the worst film writing of this or any other decade in the piece comparing it favorably to The Birds). The decision to curtail the annual award (the Jaumey?) is about loving something enough to find the courage to let it go its own way (a parable enacted in The Shallows via the relationship between Blake Lively’s shark-bitten surfer and the wounded seagull she tenderly nurses back to health). As to how we’ll cope with impending empty nest syndrome, well, hopefully there’s some skillful European rookie prepping a decent mid-budget studio thriller for us to (over?)rate any day now. Turn! Turn! Turn! —AN

Most Underrated Overrated Double Oscar Winner: Tom Hanks

Something odd has happened over the past few years, in which the appreciation, both from critics and award bodies, of America’s longtime sweetheart Tom Hanks has diminished as the quality of his work has increased. The first sign was his chin-scratching lack of an Oscar nomination for his work in Captain Phillips, perhaps the best of his career, in which a tightly clenched, unrelentingly professional demeanor, tested throughout by the tensest of circumstances, is finally wrenched open in a miraculous final catharsis. This performance set something of a template for middle-age Hanks roles: an effortless professionalism that seems constantly ready to break down from conflicts both internal and external, which can be seen in both Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies and, this year, Clint Eastwood’s economically complex anti-disaster-movie Sully, in which Eastwood and Hanks use a fairly cut-and-dried true-life hero story to question the very idea of heroism itself. Hanks seems on his way to another lack of an Oscar nomination, and while we try not to put any stock in silly awards here at Reverse Shot (his wins for far hammier work in Philadelphia and Forrest Gump should express the limitations of the Academy’s taste), it’s revealing that Hanks seems to have been taken for granted of late. Of course, invisibility should, in a sense, be any true actor’s goal. —MK

Best Closing Song: Labaich—“Life Is Life” from The Treasure

Worst Closing Song: Regina Spektor—“While My Guitar Gently Weeps” from Kubo and the Two Strings

Droll Romanian Corneliu Poromboiu wisely chose to end his unexpectedly upbeat The Treasure by sending audiences off into the stratosphere. The martial stomp and blaring synth strings of Laibach’s cover of Opus Dei’s “Life Is Life” turn the original’s silly-serious lyrics anthemic (a sample: “When we all give the power / we all give the best / every minute in the hour / we don’t think about the rest”) and cast the filmmaker’s minor key drama in a new light. You’ll leave humming. (Also, the original music video needs to be seen to be believed.) Meanwhile, the choice to let Regina Spektor breathe all over “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” for the close of Kubo and the Two Strings represents a rare misstep for the usually clever Laika animation studio. This is not just because Spektor’s cover is terribly bland, but in a stroke of grossly tone-deaf cultural appropriation, they’ve replaced Eric Clapton’s blazing, iconic electric lead with plucked shamisen, the instrument of choice for the film’s young hero. For a film that largely avoids such condescending pitfalls, to stumble so badly and memorably at the finish line also casts the film that precedes it in a different, less flattering, kind of light. —JR

Least Expected Underworld Thriller: Tickled

If you think you’ve seen every “Man, this shit goes deep” scenario under the sun, check out David Farrier and Dylan Reeve’s entertaining investigative documentary, in which Australian journalist Farrier gently inquires about a silly-sounding American “sport” called “Competitive Tickling”—in which hot young guys are tied up and mercilessly tickled for the delectation of web surfers—and is rebuffed in such a bizarre and offensive way, he can’t help but take his search to the States. And then things get really scary. That the particulars of the homoerotic tickling itself are ultimately the least shocking element of the film (softcore gay porn is just the MacGuffin here) says a lot about the many surprises in store. Tickled is hardly art—there’s nary a moment of aesthetic interest throughout—but it has narrative drive, and its insistence that nefarious forces are where you least expect them grants the film an undeniable, paranoiac urgency. —MK

Best Hug: Sigurður Sigurjónsson and Theodór Júlíusson in Rams

A film that culminates in two older, heavy, bearded, naked men engaging in a tight, desperate embrace might sound like ready fodder for the Queer film festival circuit or the old Quad Cinema. But the two men in Rams are Icelandic shepherd brothers who haven’t spoken in decades due to a feud. The embrace is one brother’s attempt to warm the other after he passed out while lost in a snowstorm, and it’s one of the most tender touches on screen this year. —JR

Worst Hijinks: The BFG

We absolutely adore Steven Spielberg, but his penchant for whirligigs and doodads and overly elaborate bits of business—which can even be seen in such serious films as Empire of the Sun and The Color Purple—reached a nadir in the endless, film-sinking scene near the center of The BFG in which a group of big and mean CG giants toss our big and friendly CG giant around like a football. It goes on…and on…and on… with little concern for gravity or narrative drive or audience patience. The battle between authentic emotional content and special effects goofing has always been a tension in Spielberg’s films, but he often has the wherewithal to know where and how to hold back. Here the technology got the better of him. The scene may have been meant to please the kiddies, but even toddlers get limits on playtime. —MK

Most Louche: Fort Buchanan

Benjamin Crotty’s debut feature follows a group of characters, male and female, straight, gay, and other, lingering in a primeval forest located at the edges of a military base, that, come to think of it, I’m not sure we ever really see. No matter. Instead we watch as the luscious cast members loll about, tempt one another, occasionally consummate, often emote. Articles of clothing seem worn only to be discarded, or prove how ill they fit a bosom or crotch. A couple could arise, and often does, from any pairing on offer. Crotty’s movie eventually hits the road and lands in Africa, but it never loses that intoxicating sense of free-floating sensuality that in some ways marks it as the gentler flipside to the systems of always-circulating desires Paul Verhoeven tracks in the far more hectoring Elle. And it’s that gentle, polyamorous playfulness that suggests it might be the wiser film as well. —JR

Scariest Movie: The Other Side

Prescient is too mild a word to describe it. When seen in Toronto in 2015, Roberto Minervini’s Louisiana-set documentary—a portrait of a heroin-addicted, white ex-con trying to get his life back together after getting out of prison and ranting, with unconcealed racist overtones, against Obama, which segues into an immersive portrayal of ultra-right militia men dreaming of and gearing up for governmental overthrow—felt like a chilling revelation, like folding back a corner of the country and peeking below to see what those of us on the coasts refused to believe existed. Seen today, post-election, the film just feels like a full-on document of today’s America, bald-faced, shameless, and tragic. And what’s miraculous is that despite all the hate-mongering and simmering violence on display, The Other Side is ultimately full of compassion and love for its wayward souls. —MK

Worst Film Criticism: “It May Be an Accident, but ‘Rogue One’ Is the Most Politically Relevant Movie of the Year” by Owen Gleiberman

In which Gleiberman, a subpar critic and thinker on his best day (I often recall his placement of the Dardennes’ Rosetta high up on his Entertainment Weekly “Worst of the Year” list way back in simpler times) attempts to recast Rogue One as yet another in a long line of Movies for Our Times. His central thesis:

“The explicit metaphorical upshot of Rogue One is that people who dream of wiping things out with nuclear weapons have to be stopped. They need to be defeated.”

Oh, really? There is a movie out there that centers around the forces of good banding together to defeat evildoers with big weapons? Owen, please tell us more about this fresh idea.

“It’s galvanizing to see a message this politically primal embedded in a Star Wars movie, since there’s always been something passive about Star Wars culture. It’s the quintessence of sit-back, drop-your-jaw, munch-your-popcorn, let-special-effects-do-the-work-for-you fantasy. In fact, you could make a case that the political environment in which we now find ourselves, where fake news is as influential as real news, and where you’d be hard-pressed to pinpoint where Donald Trump’s fantasies leave off and his policies begin, was brought to you, in part, by the paradigm shift in pop culture ignited 40 years ago by Star Wars.”

Yes, yes, I see your point. It seems from what you’re saying that Rogue One, in which a ragtag crew of adventurers tries to stop the construction and deployment of a massive space weapon, represents something wholly new to the Star Wars universe. Very interesting.

“And while I don’t want to serve up an overly tidy cause-and-effect equation, it seems naïve to imagine that the new, fake-news America has no connection to our all-fantasy-all-the-time movie culture.”

A-ha! Movies can haz fake thus Trump!

:-(

There’s so much wrong packed into this one piece of writing that it’s almost recommendable for a laugh. Yet the humor curdles quick—anyone who followed the deterioration of political journalism in the face of Trump over the past twelve months will recognize the same kind of facile, weak-tea analyses that helped a manifestly unqualified candidate skate into the highest office in the land. It’s like reading Politico gone to the movies, but somehow with even less heft. I can’t wholly begrudge Gleiberman for trying to wade into the political fray in this fraught moment. This is truly a time, if ever there was one, for cultural commentators of all stripes to step into the breach and make their words count as opposed to just making their word count. But this here is an exemplar of stroke-your-chin-thoughtfully, let-the-writer-do-the-work-for-you criticism. It goes down easy and leaves little residue behind. Dropping a turd like this and capping it with a clickbait-y title only reinforces the nefarious systems that allow fake news to flourish and real ideas and thinking of import to wither on the vine. —JR