Danger Danger!

Max Nelson on Tim and Eric Awesome Show Great Job! and Sherlock Jr.

It’s revealing that the television shows most often described as “cinematic”—from Twin Peaks to The Sopranos to Breaking Bad—are long-form dramas with sweeping narrative arcs, consistent, unbroken patterns of meaning, a strong sense of character development, and recognizable thematic through-lines: the same features that tend to get films described as “novelistic.” We often, it seems, persist in expecting TV shows to conform to a relatively traditional, conservative model for what—and how—art ought to speak to us, a model still associated primarily with the novel. In this picture, the work of art is supposed to be a thing of deep internal structural coherence, the product of an individual author’s particular genius, and a way of communicating meanings that lie outside the range of facts and evidence: emotional states, sensory impressions, ecstatic truths. Above all, the universe it creates for itself is supposed to be orderly and well behaved. But television, as a rule, is not aesthetically well behaved; it has no consistency, no individual author and no internal causal logic. Instead, it’s a messy stew of advertisements, infomercials, movie teasers, awards shows, public safety announcements, Christmas specials, educational spots, public access channels, talk shows, local news stations, Punk’d-style reality programs, and—as they say on QVC—much, much more.

In 2010, Cartoon Network’s late-night, non-kid-friendly cable platform Adult Swim aired the final episode—“Man Milk”—of a desperately strange sketch comedy show created by Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim, a pair of Pennsylvanians in their late thirties who by that point had acquired a sizeable, devout cult following. In one of the episode’s last segments, a pudgy, thirty-something man (Wareheim) sitting among bookcases and diplomas confesses what is, in this show’s world, a run-of-the-mill problem. “My name is Doctor Bill Phlemn”—his name, in traditional medical-infomercial fashion, pops up onscreen—“and my best friend is Dr. Sam Hyngus.” Cut to Dr. Sam Hyngus (Heidecker), turtle-necked, hair slicked back: “Oh, I met Bill Phlemn in college. We were dorm-mates.” Back to Bill: “We both suffer from pools of blood in our stomachs.” “There’s a simple way to treat pools of blood in the stomach,” Sam tells the camera: “You just simply be provocative, and you be… organized.”

This passage is typical of Tim and Eric Awesome Show Great Job!, which ran for five seasons on Adult Swim starting in 2007. It speaks, first of all, to Heidecker and Wareheim’s fondness for disorienting tonal shifts, odd, stilted turns of phrase (“dorm-mates”), and scatological humor (minutes earlier, the pair, dressed in matching Christmas sweaters, had taken turns lactating into each other’s mouths). It also speaks to a tension that runs through the program: Awesome Show is assaultive, jarring, and wildly unstable, but never spontaneous. Every effect is carefully calibrated, and every detail—in this case, the diplomas, the names, the attire, the weak smiles, the too-rigid postures, the slight shifts of vocal inflection—meticulously mapped out. In this sense, Awesome Show is the ideal work of art for a cultural moment in which cult appeal is manufactured rather than earned over time. It’s a ready-made jumble of shaggy-dog stories, blunt satire, crude gross-out humor, mock commercial interludes, and eighties-style computer graphics, populated by a cast of top-flight alternative comedians and amateur weirdos. (This last category includes the gold-vested exhibitionist Pierre, who plays a guru obsessed with young boys, their dads, and meat, and Richard Dunn, a struggling character actor who bears a striking resemblance to Hank Warden’s room service waiter on Twin Peaks.) Unlike the various sorts of TV programs the show sends up, its discomfiting effects are entirely intentional.

This has led many of the show’s critics—reductively, I think—to tag Tim and Eric as ironists set on taking the stock formal language of TV to its logical, grotesque extreme. And yet the pair, who met as film students at Temple College and made their TV debut in 2004 with the cult animated series Tom Goes to the Mayor, rarely allow their viewers to take a safe, smug distance from the proceedings. Watching Awesome Show, one feels less like a winking co-conspirator than a puzzled victim. The show’s world is single-mindedly designed for discomfort: every cut arrives either a second too early or a second too late; every pause in conversation stretches out a beat or two past its natural endpoint; every transition between sketches is jarring, awkward and artificial; every smile ill-timed or over-stretched; every adult-child interaction laced with pedophilic implications; every laugh closer to a gasp of pain.

Some of the show’s most successful sketches result from less perceptible manipulations. Heidecker and Wareheim have a gift for obsessively isolating and poring over tiny, fleeting facial expressions and gestural tics: Paul Rudd’s air of detached, mildly bored concentration as he watches footage of male strippers in a chrome-plated, Kubrickian control console (“Computer, load up Celery Man, please…”); the vacant, slack-jawed, droopy-eyed stare Zach Galifianakis’s acting coach takes on after one of his twelve-year-old students tells him who Kirsten Dunst plays in Spider-Man (“Spidergirl... what a great idea…it’s good stuff, yeah… Spidergirl’s nice…”); the look of brainwashed approval that spreads over a roomful of awards show attendants as they watch a “meditation for kids” program gone awry (“Now float in the air… focus on your chi… give me your dad’s email address!”). One episode is structured around a spot-on parody of grade-school level astronomy videos: Heidecker and Wareheim play two talking-head scientists struggling to convey the wonders of the universe, in the course of which they end up holding their moony, closed-mouth grins much too long at a time, stumbling over their words, weaving elaborate double entendres, and frequently trailing off into verbal oblivion. The sketch becomes a series of extended verbal pratfalls, each sentence a weighty, physical thing tripping up on its own momentum: “If you could put the universe in a tube, you’d end up with a very long tube, um, probably extending, uh, twice the size of the universe, because when you collapse the universe, it expands, and it would be, uh . . . you wouldn’t want to put it into a tube.”

To me, these runaway metaphors and strange twists of syntax have strong affinities with the slapstick routines of a very different screen comedian, one who uses no language at all. No one could sell a pratfall like Buster Keaton; when he fell, it was with legs splayed out, head literally over heels, hopelessly, pathetically off-balance. Keaton’s comedy, like Tim and Eric’s, is always threatening to spill over into full-blown disaster: each time his legs fly up, it’s easy to fear for a split second that he’ll keep falling indefinitely, that he’ll never regain his balance. Eventually, he always does get up, which is one of the principal differences between Keaton’s sense of humor and Tim & Eric’s. Once they’ve fallen, the sketches on Awesome Show rarely get their balance back.

Sherlock Jr., a 45-minute almost-feature from 1924, is one of Keaton’s funniest films as well as one of his darkest: a vision of moviegoing as wish-fulfillment device, uncontrollable nightmare, and surrogate life. In the movie’s first ten minutes, Keaton’s impoverished film projectionist, who moonlights as an amateur detective, finds himself rejected by his sweetheart’s family after a sleazy rival suitor frames him for theft. Back in his projection booth, he dozes off and dreams his way into the potboiler playing onscreen, where he is reincarnated as a cool, collected crime-solver and thrown into a whirling plot of stolen pearls, foiled assassination attempts, false mirrors, safe doors, snap disguises, magic escapes, revolving walls, kidnappings, car chases, and last-minute rescues. He wakes up to learn that he’s been restored to his sweetheart’s good graces, but once he finds himself face-to-face with her in the projection booth—his home turf—he can’t manage to make a move without glancing up for guidance at the couple onscreen. When, in a single cut, the happy lovers go from embracing to cradling newborn twins, he can only scratch his head with a priceless mix of bafflement and apprehension, like someone trying to assemble a piece of furniture from incomplete instructions.

The film suggests that movies, like dreams, depend on a fragile balance of chaos and control. For viewers to accept that the hero saves the day, beats the bad guys, and wins the lady’s heart, they have to convince themselves that all those happy outcomes are, at least partly, the result of lucky accidents and close shaves. They have to be moved by a sense of contingency; they have to believe that the hero could, if only in theory, have failed. In one of Sherlock Jr.’s late set pieces, Keaton, perched on the handlebars of a runaway bike, narrowly dodges obstacle after obstacle: the gap in a bridge that happens to be filled by two well-positioned delivery trucks; a busy intersection where every car, thankfully, turns at just the right moment; a massive incoming truck that, by a lucky fluke, turns out to be hollowed out in the middle. On one level, the joke is that he takes so long to realize what we’ve known from the start: there’s no one behind the wheel. On another level, though, there is someone behind the wheel: half of the thrill of watching the scene is marveling at Keaton’s meticulous choreography and virtuosic comic timing. Much of Keaton’s comedy works on a similar principle: the film always has to feel both carefully controlled (otherwise, it would be terrifying) and wildly out of control (otherwise it would come off as calculated, exploitative, contrived).

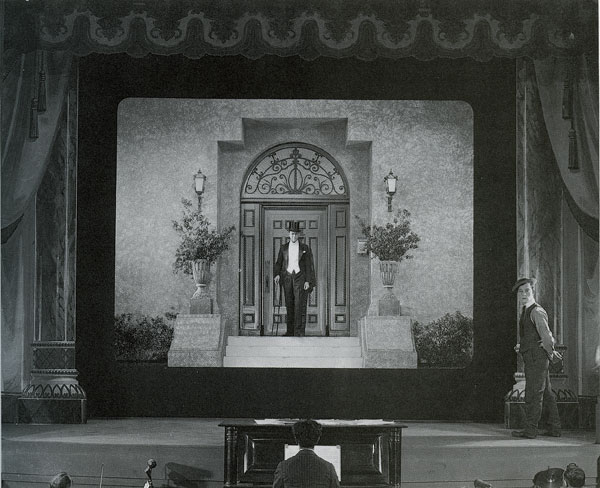

The same goes for Sherlock Jr.’s most iconic scene: stepping from the theater into the screen, Keaton finds himself tossed confusedly from one life-threatening situation to the next by a series of split-second cuts: a bustling city street gives way to a sheer cliff; a lion’s den to a field of cacti; an ocean to a forest blanketed in snow. Everything comes off as radically unstable, slippery, and disordered. Or it would, if each cut was not perfectly timed for Buster’s maximum distress, always catching him in mid-leap, mid-sit, or mid-step. This isn’t a random universe, it’s an actively malicious one—and one that’s rigidly self-contained. The bounds of the screen are clearly visible, as are the hands of the piano-player keeping time and the heads of the front-row moviegoers watching along; for all its snap disruptions and lightning-fast U-turns, the scene never spills out of the frame. There may not be spatial continuity in Sherlock Jr.’s movie-within-a-movie, but there is, at least from the audience’s perspective, a degree of harmony and coherence. The borders of the frame are firmly set, the cuts perfectly timed, and Keaton’s movements, however spastic, well-synchronized.

Tim and Eric’s world, in contrast, refuses even this basic stylistic coherence. In Awesome Show, frames are always twisting and shrinking and multiplying and dividing; on the whole, its universe is radically cluttered and haphazard. There is little to no continuity between shots—each sketch seems as if it’s been run through an editing machine that alternates between stalling and hyperactive—or within them. At the drop of a hat, a mattress store ad could give way to a bloody nightmare, or a quilting infomercial to an emotional meltdown. And yet, paradoxically, the show’s radical instability is itself the product of a meticulous design, which is arguably what makes it such a fitting model for network TV as a whole.

On one level, Tim and Eric remind us that it’s misguided to expect aesthetic refinement, causal continuity, or narrative coherence from a medium that rarely allows for them. The vast majority of network TV programming, they suggest, does conform to a kind of order, but one dictated primarily by commercial interests rather than by the demands of logic or good taste. This is, I would argue, why Awesome Show often feels at once anarchic and micromanaged, predictable and out of control. It corresponds to a medium in which seemingly aesthetic choices—what to show, when to cut, how to arrange images in sequence—have become purely economic ones, motivated by the demands of advertisers, the pull of brands, and the hand of the marketplace.

Tim and Eric have described Awesome Show as “a nightmare version of television,” in the same way, perhaps, that Sherlock Jr.’s movie-within-a-movie is a nightmare version of cinema. It’s telling, then, that Keaton’s nightmare arrives at a kind of clockwork-like equilibrium even as it spins deeper and deeper into chaos, whereas Tim and Eric’s has been carefully designed to drift farther away from aesthetic coherence with each verbal stumble and jarring cut. Both artists suggest that stepping into their respective mediums means losing one’s balance. In the case of Awesome Show, though, once you’ve started falling, it’s hard to stop.