Presidential Executive Order Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States

State of Denial

Giovanni Vimercati on Japanese Relocation

The wave of indignation and outrage that met the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States of America reflects a general inability to reckon with the past. Liberals have reacted to it as if the new President came from another planet (or was sent it from Russia, which is just as alien), an aberration prone to steer America away from its constitutional course into an illiberal future. That Trump represents a singular specimen in the history of American politics is clear, and yet at the same time he is the very outcome of its systemic failures. Blaming his election on Putin, the FBI, or the feral ignorance of the lower classes won’t help unveil the root causes of a sociopolitical disease of which Trump is the mere symptom.

Trump happens to be the living stereotype of the worst American culture has produced: sexist, ignorant, and money-obsessed. Politically then, if we are to stick to the facts, even his outrageous executive orders do not represent such a radical departure from those legendary “American values” many are worrying will be eroded by his presidency. While it is noble and brave to protest the President’s so-called “Muslim ban” (which only applies to those Muslim-majority countries Trump doesn’t do business with), it remains unclear why Hollywood celebrities and concerned liberals didn’t protest the deportation of 2.5 million “illegals” under the previous administration. Opposition to Obama’s anti-immigration policies was marginal and went unheard. Ethnic and political minorities have had a hard time in America long before Trump was sworn in. Recent American history is dotted with episodes of casual intolerance. Throughout the Cold War, for instance, members of any Communist party or organization were denied entrance to the United States, a discriminatory policy few complained about or deemed anti-democratic. The need for an enemy, be it domestic or foreign, is congenital to the American way of life, regardless of who's sitting in the Oval Office, and long predates the Trump administration.

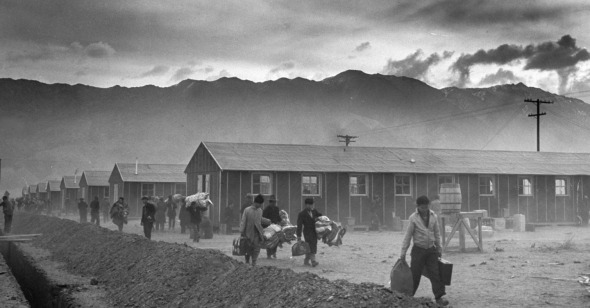

Tellingly enough, one of the most racist decrees ever issued was passed under one of America’s most progressive presidents, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose New Deal pulled the American economy out of the financial crisis in the 1930s. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FDR’s administration called for the deportation and incarceration of Japanese Americans with Executive Order 9066 (which also included measures against German and Italian Americans). “Distributed and exhibited under the auspices of the War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry,” the short Japanese Relocation was produced in 1942 and was narrated by none other than a future president’s younger brother, Milton S. Eisenhower, who at the time was director of the War Relocation Authority. The short is one of many that visually accompanied the American war effort that had mobilized Hollywood heavyweights such as John Houston, Frank Capra, John Ford, and others. Images and the grammar of cinema are unimaginatively enlisted in the service of xenophobic rhetoric leaving no room for any formal fancy. Shown in movie theaters across the nation before regular features, these newsreels, like any form of propaganda, went after audiences’ guts rather than their brains. Only this time the spelled-out message did not target the scourge of fascism but innocent Japanese-American citizens. “Neither the army nor the War Relocation Authority,” Mr. Eisenhower reassures viewers “relish the idea of taking men, women, and children away from their home,” which is why they decided to “do the job as a democracy should, with real consideration for the people involved.” Being robbed of your property by your own government on ethnic basis, prior to deportation, is helpfully translated as “quick disposal of property often involves financial sacrifices for the evacuee.” Then, just in case the spectator might start thinking that stripping a person of his belongings and taking him to a “relocation camp” might not be the most democratic of practices, the narrator is quick to point out that “the evacuees collaborated wholeheartedly,” to their own forced deportation and internment that is.

“The many loyal among them felt this was a sacrifice they can make on behalf of America’s war effort,” Eisenhower continues—after all, where they were heading, “the army provided housing and plenty of nourishing, healthy food.” On their arrival in the camps “naturally the newcomers looked about with some curiosity” for “they were in a new area, on land that was raw, untamed, and full of opportunities,” the voice-over enthuses. Even in the squalor and injustice of a prison camp the good old American Dream lived on, along with “Americanization classes” whose purpose is unclear since two thirds of the prisoners were American citizens (the remaining third, “aliens”). This ethnic-cleansing propaganda film, whose only purpose was to show “how this mass migration was accomplished,” ends on a rather disturbing note that is worth reporting here at length:

“This picture is actually the prologue to a story that is yet to be told […] it will be fully told only when circumstances permit the loyal American citizens, once again, to enjoy the freedom we in this country cherish. In the meantime we are setting a standard for the rest of the world in the treatment of people who may have loyalties to an enemy nation. We are protecting ourselves without violating the principles of Christian decency.”

To anyone still wondering where Trump’s embattled advisor Steve Bannon's toxic ideology comes from, this terrifying short provides some helpful clues. Christian fundamentalism and supremacy, be it racial or ideological, are by no means the exclusive prerogative of alt-right lunatics but are an integral part of American history (see Griffith’s Birth of a Nation for elucidating purposes). For a country such as the United States, founded on genocide and built by slaves, to consider Trump’s policies as a deviation from the righteous course of American democracy is not only delusional but dangerous—dangerous because by not recognizing the long and deep roots of “Trumpism,” its opponents will end up focusing on the symptom and not on the actual disease. Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which is the helpful word Germans use to indicate the process of coming to terms with the past, is a much-needed antidote to America’s historical amnesia, and many other countries for that matter. The internment of Japanese Americans rarely comes up today in written or oral accounts of WWII, eclipsed by the heroic exploits of American soldiers on the other side of the Atlantic.

It took Hollywood almost 50 years to deal with this dark chapter of recent history. It was only in 1990 with Come See the Paradise, directed by Alan Parker, that the persecution of Japanese Americans was dramatized on the big screen; it’s a film that, beneath its glossy veneer, makes no concessions to the severity of the story it tells. For once we are spared that ever-present character of the white middle-class male rescuing the persecuted and the reputation of the star-spangled banner. The only character that comes out in solidarity with the “Japs” in Parker’s film is actually an Irish commie. A glowing white savior does appear in the form of Ethan Hawke in 1999’s Snow Falling on Cedars, directed by Scott Hicks. Though honest when it comes to the depiction of the injustice Japanese Americans were subjected to during the war, Hicks’s film still exhorts the paternalistic virtues of the lone American hero. Which is nonetheless a step forward compared to the unsavory morale of Hell to Eternity, a 1960 film directed by Phil Karlson, one of the very first films to tangentially deal with the internment of Japanese Americans. Karlson’s film in fact downplays the gravity of this event while extolling the virtues of America’s altruism, which fought against the “Japs” also on behalf of Japanese Americans.

Seventy-five years after FDR issued Executive Order 9066 (the presidential library that bears his name has celebrated the anniversary with an exhibition), Donald J. Trump signed a somewhat analogous executive order, “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States.” Though written and conceived under different historical circumstances, and hopefully without the same consequences thanks to the U.S.’s judicial branch, which has so far thwarted its carrying out, both executive orders are rooted in the same nationalistic rhetoric that justifies discrimination in the name of security and protection (from the same irrational fears these kind of measures stoke). Expressions such as “removable aliens” or “alien enemies” lay the cognitive ground for the dehumanization of entire groups whose persecution appears to be a matter of self-defense rather than xenophobic aggression. Superficial indignation and longing for an innocent past that never was are unlikely to mine the ideological premises on which the current administration comfortably rests upon.

In the years to come expect that Donald Trump will be framed as the cause of America’s problems and not the result. Those seeking to overthrow the Trumpian paradigm cannot ignore its cultural genesis. Rather than idealized, the American past should be revisited, investigated in its least pleasant and mythical aspects like James Ellroy has done in his latest novel, Perfidia. With his desperate, misanthropic humanism Ellroy has scavenged the gutters of American history in search of those marginal characters and stories that made up its politically incorrect epic. In Perfidia the internment of Japanese Americans is observed through the criminal economy of Los Angeles, where historical characters act alongside fictional ones to conjure a reality more authentic than the one we often give for granted. If anything, Trump might end up dispelling the illusions that have underpinned American exceptionalism for all these years. Uttered by a man as baldly false as The Donald all the presidential platitudes no longer sound credible and their implicit hypocrisy cannot be mistaken for noble intentions.

The road to his outlandish declarations and actions, however, has been paved by years of televised xenophobia not only by the likes of Fox News but also by liberals like Bill Maher, whose HBO show is a regular tribune for Islamophobic tirades or by the insulting stereotypes featured in TV series like Showtime’s Homeland. Disturbingly enough, it took Trump to bomb the Middle East in order to be declared sane by the same liberal establishment that had deemed him unfit for office. The collective hysteria that allowed the uncritical acceptance of a film like Japanese Relocation is not that far from the mass Islamophobia that has characterized America after 9/11. For better or worse, moving images will once again be the witness for the prosecution in the ongoing trial of history.