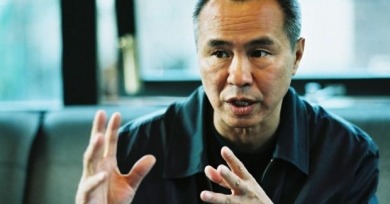

Hou Hsiao-hsien: In Search of Lost Time

Hou has made films that wrestle, variously, and either directly or metaphorically, with personal and national histories, the struggles between Taiwan and Chinese nationalism, the encroachment of capital on an ever-evolving way of life, and the legacy of cinema itself.

It’s become a cliché to say that a film floats, that it exists in reverie, yet Flight of the Red Balloon may come closer to embodying an earthbound heavenly state than any film I’ve seen.

The mid-century setting, the pop songs, the rain that falls as steam rises at a noodle stand in Huwei: we’ve seen this before, but it’s possible to talk about the segment’s failures without comparing them to Wong Kar-wai.

Overused words like rapturous and hypnotic certainly apply to Hou’s technique here, even as the film jumps between eras and political realities, yet there’s something so much greater and more challenging going on in Three Times than aesthetic control.

Yet is it possible for a critic to express his disinterestedness in a major filmmaker and not enter into polemics? Can we simply state that these films do not affect us without either impugning a talented artist or goading his supporters into indignant defense?

Café Lumière can be considered a Tokyo story in a far more literal sense. When Hou first conceived of the film, he traveled to Tokyo with a railroad map, plotting his characters’ routes according to station stops.

Hou’s films have never tethered themselves to three-act structures or straightforward narrative storytelling; rather, the director tends to privilege visuality over narrative, mise-en-scène and character over plot and event. Millennium Mambo takes these impulses to an extreme.

What does it mean to say that Flowers of Shanghai is perfect? And how could one apply the label “perfect” to the cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien, which is often improvised around a basic structure or, like Flight of the Red Balloon, created almost wholly from scratch?

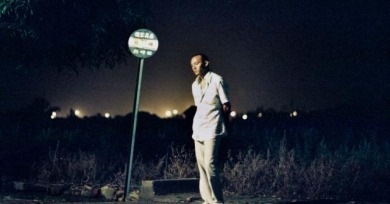

Even the title is unerring. Goodbye South, Goodbye: the phrase evokes a new beginning, the promise of motion, a regretful departure, an elegiac wallow, and sweet release, all at once. That density of suggestion pulsates in nearly every scene of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s movie.

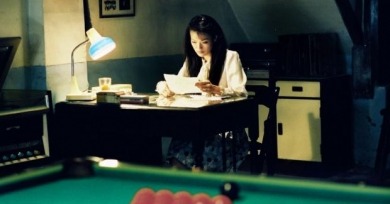

In 1995’s Good Men, Good Women, Hou seems to want to make historical consequence even more tenuous; here, he’s engaging in what seems initially to be at-arm’s-length meta-commentary.

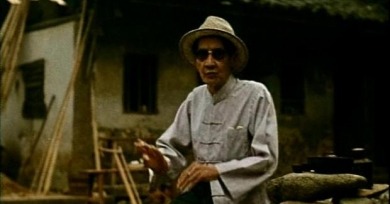

The Puppetmaster is absolutely not a film I want to reduce. I love this film. It’s the Hou Hsiao-hsien film I would take to my grave, the one many others would too. It’s just that “greatness” is not quite the right word to ascribe to such a self-effacing movie.

It’s one of the best examples I know of a film that seems to exist independently of a viewership, self-contained in its own evocation of a specific time and place.

Daughter of the Nile (1987) is one of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s least talked about, least studied works, a film nearly invisible among his post-A Time to Live and a Time to Die output.

Though plainly resembling the films which preceded it almost to the point of formula, Dust introduces a number of new elements into Hou’s stylistic and thematic repertoire. Firstly, the autobiographical locus has subtly shifted.

The subtlest of formalists, Hou Hsiao-Hsien is a director whose considerations of film language are so foundational—placement, movement, duration—as to be imperceptible, and so organic to the larger narrative as to seem nonexistent.

Despite the fact that children figure centrally in only a handful of Hou's films, his experience with them, as actors and as characters, played an important role in the early figuration of his style.

Familiarity of the personal is, perhaps, why Hou’s fourth film, The Boys from Fengkuei, leafs through the same dog-eared locations as other vignettish all-the-young-dudes remembrances like I vitelloni, Diner, and, more recently and self-consciously, Reprise.

Widely regarded as the work that ushered in the New Taiwanese Cinema, The Sandwich Man follows the lead of other omnibus films of its era, whose purpose was to give young directors a chance to explore their creativity and address social issues.

Hou began his career with three blatantly commercial romantic comedies, vehicles for the Hong Kong pop star Kenny Bee churned out in a brisk two years.