Steven Spielberg: Nostalgia and the Light

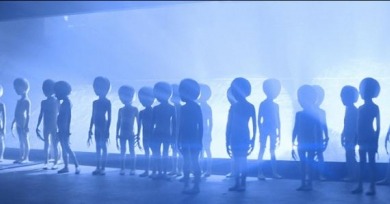

Many of our writers fall in that Spielbergian sweet spot: we were raised on E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Poltergeist, rewatching videotapes of these films until they were worn out, growing so accustomed to their mechanics that they became The Movies themselves.

In 1969, Steven Spielberg met two household names on their way down the marquee as he took his first steps up to the above-the-title rung he currently occupies.

In the director’s pre-blockbuster innocence and naiveté, he sought grittier story material that might possibly reflect the way things are, like it or not, grounding his aesthetic in a mastery of technique before attempting to blow it out with a spectacle as full of heart and utopian longing as a galactic visitation calls for.

Unlike Duel, the film feels very much like the television movie that it is, and not in small part because of the claustrophobic nature of the story.

While one would like to embrace Sugarland for what seems like modesty (at least in comparison to the grandiosity of his upcoming fish tale, and seemingly every movie after it), its aimless folksiness doesn’t become its director.

Without the pop-existentialist gloss of Duel, Jaws pointed the way towards the “classic” Spielberg cinema of wordless sensation—located anywhere on the spectrum from terror to bliss—raised to the level of the absolute, sensation shorn of anything outside our own willingness to experience it.

Even with its big budget and mass-cult appeal, it still managed to feel like a film of the American maverick era, with one foot in the future, and the other in the dusty, post-hippie, faux-wood-on-a-station-wagon present.

Arriving at the approximate midpoint between the two most devastating acts of war ever carried out on American soil, 1941 is a prophetic vision for anyone who’s thought seriously about buying some duct tape or packing their home and fleeing from residency in a major city during a crisis.

Spielberg’s approach to Raiders, and to its main character, is to make a winking allusion to, followed by the almost immediate subversion of, genre cliché.

Eight Reverse Shot writers revisit Steven Spielberg’s 1982 phenomenon.

Poltergeist, which would become one of the defining horror works of its period, was a pet project of Spielberg’s that he brought to MGM during the first pinnacle of his career.

It’s set in an old folks’ home, visited by Scatman Crothers, in fully unapologetic Uncle Remus/Bagger Vance mode (a demeaning performance which whilst quite deliberately nostalgic, must surely have felt severely dated even in 1983).

Spielberg’s hackneyed neo-Victorian depiction of pre-independence Indians represents them as either cult-worshiping savages or simple, superstitious farmers waiting for a white hero to come and rescue them.

It often feels wildly inappropriate, especially for a film so burdened by questions of racial and sexual representation. . . . it’s also a remarkable work of Hollywood mastery, and its sheer emotional impact makes it one of Spielberg’s great achievements.

Memory has no hold for a boy stunted in day-to-day survival mode, with its hunger pangs and delirium masquerading as sanity. Is that American fighter pilot really waving at Jim from his P-51 as it bombs the internment camp? Do such distinctions matter when you’ve been swallowed whole by a world gone mad?

Perhaps no other film in his oeuvre reflects so many of his preoccupations, both superficial (1940s, Nazis, boyhood, movie history) and substantive (absent fathers, fractured masculinity, the intersection between domestic strife and the threat of large-scale annihilation).

It should be re-viewed as a quintessential Spielberg film; it depicts the belief that our choices are at once motivated by a greater power and a distinct set of humane ethics. That Spielberg filters it all through classical Hollywood narrative tropes is wondrous.

The film has all the trappings of an archetypal Spielberg classic: fast-paced action spectacle; literal and figurative flights of fancy; the yearning for familial wholeness and the unearthing of youthful energy. That’s the problem. It’s a simulacrum of Spielberg wonder.

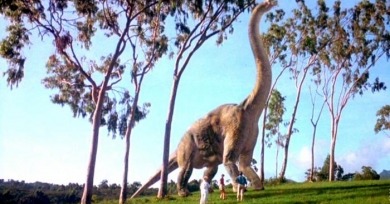

But how does a film premised mostly on succeeding in the seemingly impossible technological task—at the time—of creating lifelike dinosaurs play now in an era when the bar gets raised ever higher in terms of special effects?

Schindler’s List, as a film, has gotten lost somewhere between the reverence characteristic of its popular reception and the highly charged, theoretically driven criticism it received elsewhere.

Schindler’s introduction is arresting, chic, and even romantic in a way that immediately disrupts and, to some extent, undermines all that comes before.

Just because The Lost World is dino-tainment does not mean Spielberg’s emotionally absent from it. He takes escapism and fantasy too seriously to be a cynical “one for me, one for them” director.

It stands alone as Spielberg’s only courtroom drama, and as thus is preoccupied with concrete matters that none of his other films are, in terms both historical (that history is a reflection of a given era’s social institutions) and philosophical (that natural law needs to supersede that of the land and government).

In the wake of Ryan, realism ceased to be an aesthetic choice or strategy among countless others that might be employed to cinematically portray war; it became a de facto principle, an attitude taken for granted as the obviously correct one for approaching said material.

The first decade of the 21st century, even with all the technological changes that have greatly expanded knowledge of our origins and pointed towards our potential futures, holds no monopoly on the great unending debate of what the word “human” means.

The overall tightness of Minority Report’s scenario is remarkable, as each further story progression reinforces central questions of man’s place in and potential lack of control over his limited universe.

Jam-packed with product labels and advertising slogans and clips from TV shows and movies, this is perhaps the Spielberg film most saturated with pop culture, as well as the one that most cannily illustrates the director’s ambivalence towards it.

Looking back from our vantage, The Terminal seems an even more remarkable misfire: completely tone-deaf, uncharacteristically ham-handed, a dud amid one of the great runs by any modern American filmmaker.

Precisely what fears these sinewy tripods are intended to represent—or, indeed, whose way of life is being threatened—remains ambiguous, even as it seems clear that Spielberg wants us to think something important about our lives during wartime.

Munich remains resolutely focused on the response to terrorism and on the effects of violence, and not on terrorism itself or its root causes; terrorism is context, justification, flashback.

For over four decades, Spielberg has obsessively struggled to reconcile the opposing ideals of the modern man.

Steven Spielberg’s long-gestating, performance-captured take on the Belgian comic artist Hergé’s classic action-adventure serial The Adventures of Tintin starts with a bang and barely pauses until the credits roll a hundred or so minutes later.

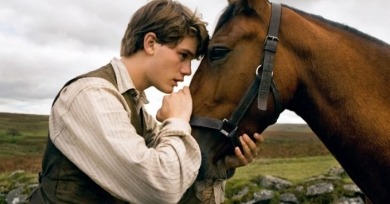

Joey is like a blockbuster version of Bresson’s Balthazar—a patient witness to joy and terror, who only gets dangerously excited when pushed to extremes.